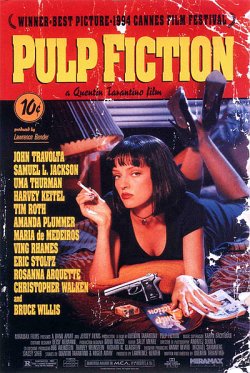

Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction, a stunning follow-up to his equally brilliant directorial debut, the ultra-violent Reservoir Dogs, is probably the most morally subversive movie to come out of the Disney Empire. (Miramax, which distributes the film, became part of Disney in 1993).

While this is an interesting curiosity item, far more significant is the towering achievement of Pulp Fiction as one of the freshest, best-written, best-directed American movies of the year. It’s also one of the most enjoyable experiences I have had in a long time.

Some of us “discovered” Pulp Fiction in May, at the Cannes Film Festival. As soon as the film was shown, the festival was over, so to speak, as it became clear that it would win the top prize, the Palme d’Or.

Pulp Fiction draws its inspiration from the lurid low-life characters found in the cheap yellow pages of l930s and l940s crime novels. Set in a modern-day Hollywood, the picture is populated by two-bit hoods, gangsters, corrupt cops, and “black” widows wearing earrings where most people have underwear. Thrown into this colorful mix are two talkative hit men (John Travolta and Samuel Jackson), a double-crossing prize-fighter (Bruce Willis), an exotic drug-addled wife (Uma Thurman), and a pair of young lovers (Tim Roth and Amanda Plummer) contemplating an all-important career change–whether to hold up restaurants instead of liquor stores.

Some directors and critics have resented the enormous publicity that Tarantino and his movie have been getting since May and the aggressive marketing that Miramax has been using to promote their picture. But critics should not underestimate Tarantino’s accomplishment just because of the hype the film has generated.

The hottest filmmaker at present, Tarantino has become a crucial figure in the new American cinema. He has replaced Martin Scorsese as the innovative and gutsy role model for younger and aspiring filmmakers. Like Scorsese, Tarantino is a consummate cineaste who knows movies inside out. Unlike Scorsese, though, Tarantino didn’t go to film school; instead, he got his education working in a video store for a number of years.

There are important thematic links between Scorsese’s and Tarantino’s oeuvre. Intertextuality, as we say in film studies, is the strategy used by both directors who, among other things, don’t show contempt for Hollywood’s “despised” genres, i.e. melodramas and crime movies. Quite the contrary: Scorsese and Tarantino use the conventions of “B” movies to make their own versions of European art films, specifically influenced by the French New Wave.

Reservoir Dogs and Pulp Fiction are based more on old movies than on life itself. If the former picture was too self-conscious about the noir tradition, the new one cannot be understood unless it is placed in the tradition of pulp novels and films.

But is it fair to complain about a director whose screenplays are exuberantly witty and who gets the best performances out of his actors Bruce Willis, who’s almost unrecognizable in Pulp Fiction, gives one of his most inspired performances, finally getting rid of his notorious smirk. People are also bound to talk about John Travolta’s impressive comeback after a whole decade of existence in the margins, and about Samuel Jackson’s showy work.

Pulp Fiction, like Reservoir Dogs, boasts an audacious narrative structure. It consists of the three interconnected stories, each centering on two characters. The first duo are lovebirds Honey Bunny and Pumpkin (Plummer and Roth), whom we meet in a coffee shop as the story begins. The second–and central–couple–are Vincent (Travolta) and Jules (Jackson), hit men working for jealous crime boss Marsellus Wallace (Ving Rhames). In the third tale, the heroes are Marsellus and his washed-up boxer Butch (Willis) who’s ordered to take a dive.

The film’s other interesting characters are women. In the self-enclosed world of Reservoir Dogs, there was no room for women, but in Pulp Fiction one of the central figures is Mia (Thurman), Marsellus’ sexually alluring wife, whose date with Vincent provides one of the film’s most satisfying scenes.

Tarantino boldly neglects Hollywood’s golden rules of plot mechanics and linear narratives in favor of long scenes that are presented out of sequence. But the ultimate glories of Pulp Fiction reside in its witty dialogue and inspired playfulness. Tarantino shows passion for the music and rhythm of words–big words. For example, as Vincent and Jules drive to their first lethal mission, they talk at length about fast food in Europe, and bicker about whether a foot massage counts as a sexual act. This may be one of the ironies of Tarantino’s work: He makes crime pictures with very little action. His protagonists, who spend more time talking than killing, seem to enjoy better their conversations than their actions.

Tarantino’s love for dialogue set-pieces makes him also a venerable actors’ director. Unlike most American action movies, in which actors have to compete with the special effects to get some attention, actors are not incidental to Tarantino’s movies. With all the bravura style that Polish cinematographer Andrzej Sekula brings to the film, when two characters converse, the camera doesn’t move much. Instead, it gracefully observes the actors’ verbal and gestural communication. Tarantino’s respect for his actors means that they are never upstaged by visual orsound effects.

Pulp Fiction is also stylistically innovative. The Los Angeles Tarantino depicts is not the one we are used to see in noir films, which are mostly set at night–and indoors. It’s also not the chic or glamorous L.A. that informed Down and Out in Beverly Hills, Pretty Woman, and recently Michael Tolkin’s The New Age.

Most of the events in Pulp Fiction are set in the sun-blasted sprawl of L.A., though there are no palm trees, no shots of the beautiful ocean, no reference to the Hollywood sign. What replaces these icons are barren streets, dilapidated buildings, and plain coffee shops–in short, a squalid milieu.

I hope the movie’s hype won’t deter you from seeing Pulp Fiction, which is much more than a cool exercise in style. Situated in Scorsese’ macho world (Mean Streets, Taxi Driver, GoodFellows), Pulp Fiction is a serio-comic meditation on honor, loyalty, redemption, and manhood. But in tone and sensibility, the movie goes further than Scorsese. Tarantino understands that his movies are as much a reflection of pop culture as they are pop culture themselves. He therefore refuses to sentimentalize his heroes or force them to repent–as Scorsese does in his movies in a quasi-religious way. Tarantino’s heroes are as hip, lurid, and self-reflexive as befits that uniquely American genre called pulp fiction.

Some critics (a minority, I might add), such as Philip Lopate, thought that Pulp Fiction was too much of celebration of mindlessness and an assertion that nothing matters more than pulp fiction.

End Note

According to the scholar Robert Kolker, Tarantino was particularly attentive to Scorsese’s 1978 documentary, “American Boy,” a painful but hilarious monologue, Stephen Prince (who played Andy the Gun fence in “Taxi Driver,” tells a strange story of reviving a woman suffering from a drug overdoze by plunging a syringe full of stimulant into her heart, which became one element of the plot of “Pulp Fiction.”

Speak Your Mind