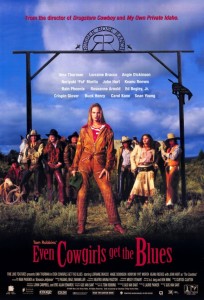

In 1993, avoiding typecasting as a director with narrow (male-oriented) range, Van Sant made a radical shift from the all-male terrain of “My Own Private Idaho” to the nearly all-female turf of Tom Robbins’ feminist manifesto, “Even Cowgirls Get the Blues.”

In 1993, avoiding typecasting as a director with narrow (male-oriented) range, Van Sant made a radical shift from the all-male terrain of “My Own Private Idaho” to the nearly all-female turf of Tom Robbins’ feminist manifesto, “Even Cowgirls Get the Blues.”

Grade: C (* 1/2* out of *****)

His first flop, both commercially and artistically, “Even Cowgirls” was the equivalent of the “sophomore jinx” that Soderbergh had experienced with his second feature, “Kafka,” in 1991, after the strong impact of “sex lies and videotape.” Except that in Van Sant’s case, it was his fourth feature, excluding “Alice in Hollywood.”

The movie boasted Van Sant’s biggest budget ($8.5 million) to date, and a large eclectic cast, including Uma Thurman, John Hurt, Keanu Reeves, and a newcomer, River Phoenix’s younger sister, Rain (at River’s own suggestion). Testing poorly, the film was worked and reworked, but the end result remained disappointing. In my view, “Even Cowgirls” is one of weakest films Van Sant has made.

Going into the film promised a different kind of challenge and fun, and Van Sant was glad to announce that in “’Even Cowgirls,’ you don’t really get this sex-object angle, although at the same time you get the feeling that the writer is living in a fantasy in sex-object land. It’s sort of this other world, a city of women. The whole project is a great women’s film.”

Going into the film promised a different kind of challenge and fun, and Van Sant was glad to announce that in “’Even Cowgirls,’ you don’t really get this sex-object angle, although at the same time you get the feeling that the writer is living in a fantasy in sex-object land. It’s sort of this other world, a city of women. The whole project is a great women’s film.”

In this particular case, like Almodovar, Van Sant evoked the spirit of the great gay “woman’s director” George Cukor: “It’s a chance to make the ultimate remake of ‘The Women,’ which is a beautiful Cukor film from the 1930s.[i]

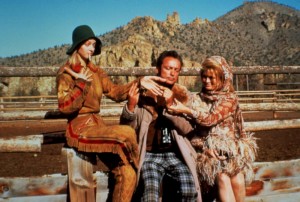

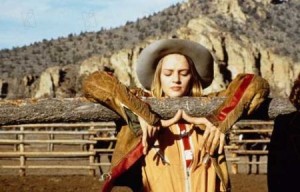

The reality of this film, however, proved much different. The most original element about this misconceived picture is its title, deriving of course from the novel–it’s hard to beat that. Barely a year before she would be catapulted to stardom in Quentin Tarantino’s “Pulp Fiction,” Uma Thurman stars as Sissy, a woman destined to be the world’s greatest hitchhiker. Flaunting nearly flawless beauty and oversized thumbs, she is crisscrossing the country. Due to her large thumbs, Sissy grows up to become a beautiful woman and a champion hitchhiker. In due time, she serves as the chief model for the Countess (John Hurt), a transsexual from Mississippi who has made a fortune in the hygiene industry. Her lucrative career involves work as a spokesperson for the Yoni Ym line of women’s products made by the Countess. In the 1970s, the Countess summons Sissy, who is still a virgin, to Manhattan to meet Julian Gitche (Keanu Reeves), a Native American artist who’s asthmatic. In a typical Van Santian mode, the mating between the two fails. Sissy incurs the wrath of the government, when she joins a group of radical cowgirls who live in Rubber Rose, the Countess’ commune in the Dakota Badlands. Fellow cowgirl Delores Del Ruby (Lorraine Bracco) sees the migration of the whopping crane as crucial to their political battle with the FBI.

The reality of this film, however, proved much different. The most original element about this misconceived picture is its title, deriving of course from the novel–it’s hard to beat that. Barely a year before she would be catapulted to stardom in Quentin Tarantino’s “Pulp Fiction,” Uma Thurman stars as Sissy, a woman destined to be the world’s greatest hitchhiker. Flaunting nearly flawless beauty and oversized thumbs, she is crisscrossing the country. Due to her large thumbs, Sissy grows up to become a beautiful woman and a champion hitchhiker. In due time, she serves as the chief model for the Countess (John Hurt), a transsexual from Mississippi who has made a fortune in the hygiene industry. Her lucrative career involves work as a spokesperson for the Yoni Ym line of women’s products made by the Countess. In the 1970s, the Countess summons Sissy, who is still a virgin, to Manhattan to meet Julian Gitche (Keanu Reeves), a Native American artist who’s asthmatic. In a typical Van Santian mode, the mating between the two fails. Sissy incurs the wrath of the government, when she joins a group of radical cowgirls who live in Rubber Rose, the Countess’ commune in the Dakota Badlands. Fellow cowgirl Delores Del Ruby (Lorraine Bracco) sees the migration of the whopping crane as crucial to their political battle with the FBI.

During the long days and nights on the Rubber Rose Ranch, Sissy befriends the beautiful Bonanza Jellybean (Rain Phoenix), who finds a new use for Sissy’s thumbs. A mysterious foreigner, known only as the Chink (Pat Morita), enters into Sissy’s world. Describing himself as the guardian of the universe’s secrets, the Chink offers to pass his wisdom onto her. The long, verbose nocturnal scenes between Sissy and Chink are boring, almost bringing the film to a halt.

During the long days and nights on the Rubber Rose Ranch, Sissy befriends the beautiful Bonanza Jellybean (Rain Phoenix), who finds a new use for Sissy’s thumbs. A mysterious foreigner, known only as the Chink (Pat Morita), enters into Sissy’s world. Describing himself as the guardian of the universe’s secrets, the Chink offers to pass his wisdom onto her. The long, verbose nocturnal scenes between Sissy and Chink are boring, almost bringing the film to a halt.

Most of the tale is set within the ranch where the cowgirls are led by Bonanaza who becomes Sissy’s lover. Violence erupts, when one of Sissy’s thumbs is amputated. She continues to travel, while keeping contact with Bonanza. From that point on, the narrative, thin in the first place, loses the little energy that it has. The cowgirls hold hostage the country’s last surviving flock of cranes. Sissy arrives just in time to witness the cowgirls and the ranchers holding off the authorities who demand custody of the cranes. The cowgirls decide to surrender, but in the process Bonanza gets killed by the ruthless government agents. In the unsatisfying resolution, the Chink, who had been living with Sissy and Delores, leaves for Florida.

Most of the tale is set within the ranch where the cowgirls are led by Bonanaza who becomes Sissy’s lover. Violence erupts, when one of Sissy’s thumbs is amputated. She continues to travel, while keeping contact with Bonanza. From that point on, the narrative, thin in the first place, loses the little energy that it has. The cowgirls hold hostage the country’s last surviving flock of cranes. Sissy arrives just in time to witness the cowgirls and the ranchers holding off the authorities who demand custody of the cranes. The cowgirls decide to surrender, but in the process Bonanza gets killed by the ruthless government agents. In the unsatisfying resolution, the Chink, who had been living with Sissy and Delores, leaves for Florida.

“Even Cowgirls” lacks the narrative momentum, distinctive rhythm, and the lyrical touches of Van Sant’s previous efforts. Thematically, though, “Even Cowgirls” belongs to Van Sant’s distinctive universe. All of his films are structured as odysseys of outsiders, journeys that celebrate the openness and endless possibilities of American life on the road. The oversized thumbs of Sissy make her an outcast who very much belongs to Van Sant’s gallery of outsiders, and her odyssey is just as random and unpredictable as theirs. In his good films, “Mala Noche,” “Drugstore Cowboy,” and “My Own Private Idaho,” the stories are told through the subjective perspective of their characters. “Even Cowgirls” failed due to its lack of clear perspective and consistent P.O.V. The protagonist, Sissy, remains, as Van Sant himself has said, “An object that you’re watching, as opposed to someone you’re watching the world through.”

“Even Cowgirls” lacks the narrative momentum, distinctive rhythm, and the lyrical touches of Van Sant’s previous efforts. Thematically, though, “Even Cowgirls” belongs to Van Sant’s distinctive universe. All of his films are structured as odysseys of outsiders, journeys that celebrate the openness and endless possibilities of American life on the road. The oversized thumbs of Sissy make her an outcast who very much belongs to Van Sant’s gallery of outsiders, and her odyssey is just as random and unpredictable as theirs. In his good films, “Mala Noche,” “Drugstore Cowboy,” and “My Own Private Idaho,” the stories are told through the subjective perspective of their characters. “Even Cowgirls” failed due to its lack of clear perspective and consistent P.O.V. The protagonist, Sissy, remains, as Van Sant himself has said, “An object that you’re watching, as opposed to someone you’re watching the world through.”

Though it was nice to see Van Sant working with a diverse group of talented actresses, such as Thurman and Bracco, he didn’t get particularly strong performances from them. Coming right after “My Own Private Idaho,” and serving as the opening night of the prestigious Toronto Film Festival, made the film all the more visible and vulnerable to criticism. Fine Line, which distributed the film, took a major loss.