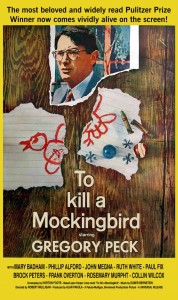

To Kill a Mockingbird combines the best elements of the Southern Gothic tradition with those of the courtroom drama, resulting in a flawless literary adaptation of Harper Lee’s 1960 Pulizer Prize winning novel.

The DVD edition includes several bonus features. Disc 1 contains Gregory Peck’s speech after winning the Best Actor Oscar for his performance as Atticus Finch, as well as his memorable remarks upon receiving the AFI Life Achievement Award.

There’s also interview with Mary Badham, who played Peck’s daughter in the film, “Scout Remembers,” in which she talks about her experiences working with Peck. The heartwarming farewell of Peck’s daughter, Cecilia, at the Academy Tribute to Peck, are included, as well as the theatrical trailer and a feature commentary with director Robert Muligan and producer Alan Pakula (before he became a director).

There’s also interview with Mary Badham, who played Peck’s daughter in the film, “Scout Remembers,” in which she talks about her experiences working with Peck. The heartwarming farewell of Peck’s daughter, Cecilia, at the Academy Tribute to Peck, are included, as well as the theatrical trailer and a feature commentary with director Robert Muligan and producer Alan Pakula (before he became a director).

On Disc 2, there is “A Conversation with Gregory Peck,” produced by daughter Cecilia and Linda Saffire and directed by Oscar-winner Barbara Kopple, which takes you inside the personal life of her father. It contains interesting info about the actor and the humniatrian man, especially in the scenes with Lauren Bacall, Martin Scorsese, President Bill Clinton, and Peck’s own family members.

Set in Maycomb, Alabama, it tells its story from the point of view of Jean Louise, nicknamed Scout (played by Mary Badham), a six-year-old child.

Set in Maycomb, Alabama, it tells its story from the point of view of Jean Louise, nicknamed Scout (played by Mary Badham), a six-year-old child.

It begins with her voice-over narration by the mature Scout, looking back: “Maycomb was a tired old town, even in 1932, when I first knew it.” It was a town where “the day was twenty-four hour long, but it seemed longer. There’s no hurry, for there’s nowhere to go and nothin’ to buy, and no money to buy it with.”

The movie begins and ends as a dream. “The summer that had begun so long ago had ended, another summer had taken its place, and a fall, and Boo Bradley had come out.” It’s just before dawn when we first see the town, surrounded by cotton farms, pinewood, and hills. The town is dominated by the Courthouse Square; the second part of the film consists of one long sequence of a trial. Maycomb is a poor town: the Depression and the crash had hit its folks really bad, the farmers the hardest.

The inhabitants pay Atticus Finch (Gregory Peck) for his legal services with hickory nuts, because there is no cash to pay with. Finch, who is a respected but not prosperous lawyer, serves as the town’s moral center. A young widower, he is a father to two kids, Scout and Jem (Phillip Allford), her 10-year-old brother. Finch gives his children a progressive education, instructing them: “You never really know a man until you stood in his shoes and walk around in them.”

The inhabitants pay Atticus Finch (Gregory Peck) for his legal services with hickory nuts, because there is no cash to pay with. Finch, who is a respected but not prosperous lawyer, serves as the town’s moral center. A young widower, he is a father to two kids, Scout and Jem (Phillip Allford), her 10-year-old brother. Finch gives his children a progressive education, instructing them: “You never really know a man until you stood in his shoes and walk around in them.”

The movie deals with the growing pains of the two siblings and Dill (John Megna), a seven-year-old boy from Meridian, Mississippi, who spends two weeks in town with his aunt Stephanie. They are all products of broken families: The mother of the Finchley’s kids is dead, and Dill doesn’t have a father.

The importance of movies, as the nation’s major forms of entertainment during the Depression years, is conveyed when Dill recounts how his mother entered his photo in the “Beautiful Child Contest,” and won five dollars. “She gave the money to me and I went to the picture show twenty times with it.”

The importance of movies, as the nation’s major forms of entertainment during the Depression years, is conveyed when Dill recounts how his mother entered his photo in the “Beautiful Child Contest,” and won five dollars. “She gave the money to me and I went to the picture show twenty times with it.”

In her narration, Stout says: “Maycomb had recently been told that it had nothing to fear but fear itself.” The trial serves as a collective ritual in which the town’s values are tested and then reaffirmed. It’s a ceremonial occasion for the residents to feel integrated into something larger than themselves. All the town’s officials are present at the trial: Sheriff Heck Tate and the Circuit Solicitor Mr. Gilmor.

People are attending the trial from all over the region. One wagon is loaded with women, all wearing cotton sunbonnets and dresses with long sleeves. Other men ride horseback, and one rides on a mull. It’s clearly the most important event in a long time. “I’m not gonna miss the most excitin’ thing that ever happened in this town!” says Jem to her father when he is reluctant to let her watch the trial.

People are attending the trial from all over the region. One wagon is loaded with women, all wearing cotton sunbonnets and dresses with long sleeves. Other men ride horseback, and one rides on a mull. It’s clearly the most important event in a long time. “I’m not gonna miss the most excitin’ thing that ever happened in this town!” says Jem to her father when he is reluctant to let her watch the trial.

Some of the town’s residents are scary. The elderly and austere Mr. Bradley (Richard Hale) is described by Jem as “the meanest man that ever took a breath of life.” Bradley keeps his mentally retarded son, Boo (Robert Duvall, in his first, astonishing screen role) chained to a bed, like a dog. Boo even looks like a dog, his teeth are yellow and rotten, his eyes popped, and he drools most of the time.” The kids believe that Boo “eats raw squirrels and all the cats he can catch.”

During their maturation, the children become aware of their own prejudices. Fearing their old neighbor Bradley (Richard Hale), they try to track him down. When they are attacked by their father’s enemy, Bob Ewell (James Anderson), they experience real fear for the first time in their lives. But theyre saved by the one person they dreaded the most, Boo, who turns out to be a good neighbor. Says Scout: “He gave us two soap dolls, a broken watch and chain, a knife–and our lives.”

Aunt Stephanie is a stock character, the town’s spinster and gossip. Mrs. Henry Lafayette Dubose sits on the front porch in her wheel chair, while Jessie, a black girl, tends to her needs. Keeps a Confederate pistol on her lap under the shawl, Mrs. Dubose is a woman that “will kill you quick as look at you.”

Aunt Stephanie is a stock character, the town’s spinster and gossip. Mrs. Henry Lafayette Dubose sits on the front porch in her wheel chair, while Jessie, a black girl, tends to her needs. Keeps a Confederate pistol on her lap under the shawl, Mrs. Dubose is a woman that “will kill you quick as look at you.”

Established customs are observed: “Neighbors bring food with death, and flowers with sickness, and little things in between.” The rigid stratification system is in operation at the courthouse. Reverend Skies, the black Baptist preacher, enters the colored balcony, and four black men, seated in the front row, get up and give their seats. There are no townsfolk on the jury, which is composed of farmers.

Atticus Finch’s lengthy speech, one of the longest in film history, is the film’s centerpiece. Atticus is defending Tom Robinson, a black man accused of raping a white girl. Atticus has “nothing but pity” for the accused, “a victim of cruel poverty and ignorance.” “She has committed no crime, she has merely broken a rigid and time-honored code of our society. A code so severe, that whoever breaks it is hounded from our midst as unfit to live with. She was white, and she tempted a Negro. She did something that in our society is unspeakable. She kissed a black man.” “No code mattered to her before she broke it, but it came crashing down on her afterwards.”

Prejudice and racism are rampant in town. Atticus blames the State witnesses for being confident that the jury members “would go along with them,” on the evil assumption that all Negroes lie, all Negroes are basically immoral beings, all Negro men are not to be trusted around our women.” “It’s a sin to kill a mockingbird,” Atticus says, explaining the film’s title, “because it didn’t do anything but make music for us to enjoy.”

Prejudice and racism are rampant in town. Atticus blames the State witnesses for being confident that the jury members “would go along with them,” on the evil assumption that all Negroes lie, all Negroes are basically immoral beings, all Negro men are not to be trusted around our women.” “It’s a sin to kill a mockingbird,” Atticus says, explaining the film’s title, “because it didn’t do anything but make music for us to enjoy.”

A Lincolnesque figure, Atticus is the righteous idealist, or as Jem describes him, “a man born to do our unpleasant jobs for us.” Indeed, when the jury finds Tom guilty, despite evidence to the contrary, Atticus continues to believe firmly “in the integrity of our courts and in the jury system. That is no ideal to me. It is a living, working reality.” “In this country, our courts are great levellers. In our courts, all men are created equal.” Later, the heartbroken Atticus has the painful job of informing Tom’s parents that Tom was shot by the police, while breaking loose and running,

The story conveys effectively the children’s initiation into the adult world. Scout is taught by Calpurnia (Estelle Evans), the black housekeeper, how to be feminine and behave like a lady. The scene in which Scout wears a dress for the first time echoes the last scenes in “The Member of the Wedding,” in which the tomboy Frankie (played by Julie Harris) finally wears a dress. The children learn about poverty, the justice system, humility, and compassion for other people’s problems. Above all, they also learn to respect their father for what he does.

The American Film Institute (AFI) has selected To Kill a Mockingbird as one of the top 50 American films of all times. A prestige production, the film had literary cache, based on Harper Lee’s l960 Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, and also benefited from the fruitful collaboration between producer Alan Pakula and director Robert Mulligan.

The American Film Institute (AFI) has selected To Kill a Mockingbird as one of the top 50 American films of all times. A prestige production, the film had literary cache, based on Harper Lee’s l960 Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, and also benefited from the fruitful collaboration between producer Alan Pakula and director Robert Mulligan.

To Kill a Mockinbird featured prominently in the 1962 Oscar race, winning three major awards. Gregory Peck, in a perfectly suitable role, concentrated all his acting energies on the courtroom scene, the most powerful in the film, a nine-minute close-up speech delivered to the jury, i.e. the audience. In addition to Best Actor and Adapted Screenplay for Horton Foote, the movie also won the Black-and White Art Direction and Set Decoration Oscar.