In 2019, Regina King was named by Time magazine one of the 100 most influential people in the world, largely based on her achievements as Oscar winner (playing a troubled mother in Barry Jenkins’ If Beale Street Could Talk) and TV performer, right now appearing in the medium’s hottest show, Watchmen. This year, she again may be placed on the lucrative list, but for different accomplishment, her highly acclaimed directing debut, One Night in Miami.

The film world-premiered to great acclaim at the Venice and Toronto Film Festivals, and has been chosen as center piece for the upcoming New York Film Festival. Amazon has acquired the film’s rights and will release it in time for the upcoming awards season.

Far from being an overnight success, King has paid her dues as an actor. She had first gained attention for her role in the television series “227,” which ran from 1985 to 1990. She then rose to prominence with roles in black-themed movies, Boyz N the Hood (1991), Poetic Justice (1993), Friday (1995), and expanded her base with supporting roles in popular pictures like Ray (2004) and Miss Congeniality 2 (2005). Her TV resume is even more impressive, having appeared in the crime TV series “Southland,” 2009–2013, the sitcom “The Big Bang Theory,” from 2013 to 2019. King starred in the ABC anthology series American Crime, in 2015-2017, for which she won two Primetime Emmy Awards, and in 2018, she starred in the Netflix miniseries, Seven Seconds, earning her third Emmy Award.

It’s not the first time that King is behind the cameras, having helmed episodes for television shows like “Scandal” in 2015 and 2016, and “This Is Us” in 2017. But One Night in Miami holds a special place in her evolving career, as well as in Hollywood of the new era of post-“Me Too,” Time’s Up,” and “Black Lives Matter,” indicating a positive, if slow, change in issues of representation, diversity, and inclusion.

When One Night in Miami world-premiere at the Venice Film Festival, King became the first African-American woman to have an official selection in the world’s oldest film festival (celebrating its 77th anniversary).

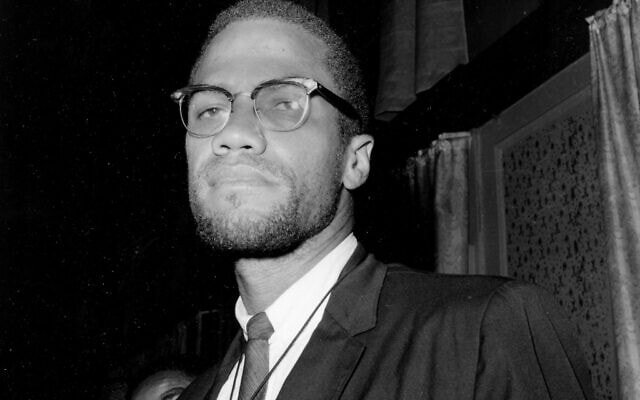

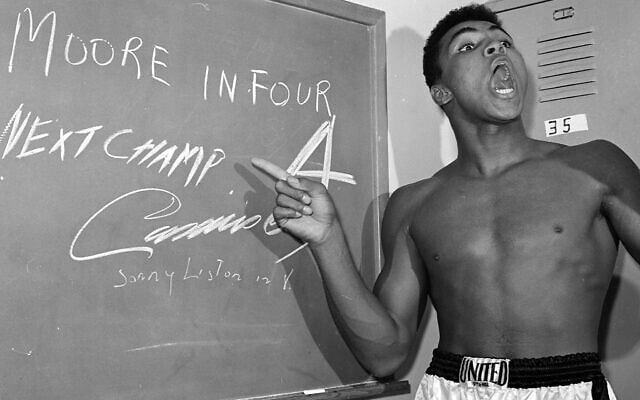

The screenplay by Kemp Powers is based upon his stage play of the same name. A meditative reflection–sort of what if–on larger-than-life figures, the film tells a fictionalized story of Cassius Clay, Malcolm X, Jim Brown, and Sam Cooke as the group meet win in a Miami hotel room on February 25, 1964. The movie takes place the night that Cassius Clay, at 22, won the world heavyweight championship by defeating Sonny Liston in a title bout at the Miami Beach Convention Center. To celebrate his victory, he heads over to the modest, rather shabby small suite where his friend Malcolm X is staying at the Hampton House, a motel that caters to Black celebs. There, the two are joined by the football superstar Jim Brown and the soul legend Sam Cooke. Though fictionalized or speculated, the four really were friends, and this get-together really did take place, but not much is known about it.

Why this project?

Discussing her motivation to do the movie, King says: “The things that are being discussed in the film are just as relevant now as they were half a century ago. And that was also a major factor for for doing it. I couldn’t believe that this was even a play, because it didn’t feel like a play when I was reading it. But more importantly, I had never seen conversations like those on the American screen, small screen or big screen. I felt that through the voices of these legendary men, I was listening to conversations from black men speaking about their personal experiences as black men.”

As always, there was also a practical matter: “I had just signed on with a new literary agent. We’d been talking about the things I was interested in doing as a director, making a move into the feature world. For a long time, I had been wanting to direct a film that was a love story with significant historical backdrop. Then my agent brings me ‘One Night in Miami.’ I mean, talk about asking for something and then it coming back–and much bigger than I could possibly imagine. I put on my presentation hat, because I had to get the job, and I met the producers. Thank goodness, Kemp and the rest of the team wanted to have me onboard.”

“We did not know what the filmmaking protocols were going to be. We talked about whether we should push back the release, what kind of premiere we would have because of Covid19. But then I felt like it was urgent to get it out Right Now, and we did! I luckily was able to be editing while we were waiting to see what the climate of the world was going to be. And then the Jewish story happened. And then Rihanna, happened. and then robbery happened. And then fast-forward, Brianna Taylor, and George Floyd. People were exploding on the streets. We were now in this amazing moment and the producers and I were like, “we’ve got to figure out a way to get this movie right now!”

.

King emphasizes that her movie is not a collective biopic of four “great men,” nor is it a didactic tale of political ideologies: “My intent was to show how these men, loosened up by drinks and the pleasure of their company, reveal themselves as individuals, not as important celebs, to show what they think, how they feel, how they spend their leisure.” Asked if there one dialogue, one moment, in the film which is the most vitally important today, she is quick to answer, “Yes, black people being murdered on the streets every day. That is a fact, and a fact that has happened less than a week ago. It happened while shooting our film, while editing if, and in this moment right now, when we present it. It’s truly heartbreaking.”

“I’ve had conversations with them individually, separate from each other, and we’ve had deep conversations on the set together as we were figuring this out. What was most important for me is that their perspective of telling of this story would matched mine. Because that was the only way to do the film in the amount of time and money that I was given and within budget.”

“We all were in agreement of the particular story we’re going to tell and the importance of pouring your heart, mind, and soul into these men. That’s a huge responsibility because everybody knows what these celebs look like. And there are other performers of real life people that have been done before us (she’s referring to Denzel Washington in Spike Lee’s 1992 biopic, Malcom X). But a lot of times the audience doesn’t know what that person really felt like back then, what he talked about with his friends, how he relaxed and drank with is friends.”

“Everybody thinks they know everything there is to know about these four giant men, so my task could have been too daunting. It could have been so difficult to step into this realm, and they all understood the particular tasks. The actors knew that I was not expecting mimicry or impersonations, that they need to portray iconic human beings from a more personal and private space that no one’s ever seen before.” In this meeting-of-the-minds, which places four legends in a single room, the verbal ideological fireworks fly alongside some more personal (even trivial) moments (the quartet joking about liking vanilla ice cream).

King has opened up the action, blending scenes set outside the motel room, like the Liston fight, and several encounters that show the characters on their own, confronting what racism circa 1964. Take Brown’s meeting with a seemingly friendly white Southerner (played by Beau Bridges), which ends on a sour note. Or observing the anxiousness of Malcolm at home in Chicago with Betty Shabazz (Joaquina Kalukango) and the tensions in their marriage.

The four are unwinding in a motel room, matching wits and ideas and teasing out their underlying rivalries. The actors — Eli Goree (Cassius Clay), Kinglsey Ben-Adir (Malcolm X), Aldis Hodge (Jim Brown), and Leslie Odom Jr. (Sam Cooke) burrow their way into the psyche of these legends, into their manners, contradictions, and vulnerabilities. Goree understates the music of Clay’s voice, and Hodge invests Brown with a wary force. Leslie Odom Jr., from “Hamilton,” makes Cooke smooth on the surface, but roiling underneath. Says King: “The men are suffused with their destinies, but they’re also funny, earthy, and relatable.”

The theme that runs throughout the film, but is given a name only at the end is “Black power.” In 1964, that phrase was just emerging, beginning to get into the collective consciousness and discourse. King observes: “One Night in Miami is set when Black Power was an idea, emerging, in part, from how these four were becoming influential stars, They were challenging the status quo, aiming to change it radically. Revolution was in the air, yet only Malcolm X has the courage to name it as such.”

She elaborates: “They’re united in their dream of the future, and their love for each other is apparent, yet they also represent some contradictions. Clay is about to announce that he’s becoming a Muslim and that he is joining the Nation of Islam, a move that will not endear him to a white press that already questions his aggressive style; he says that he was inspired by professional wrestling Gorgeous George.”

Yet Malcolm is about to part ways with the Nation himself. His bodyguard Kareem stands outside the door like a prison guard. Malcolm’s disenchantment with the Nation of Islam stems from his discovery that its leader Elijah Muhammad is a fraud. In abandoning the Nation, he’s true to himself, but he knows that it would have impact.” As expected, Kingsley Ben-Adir invests Malcolm X with intellectual fury, but there’s als0 evidence of human kindness and puritan sternness. At 39, he’s older than the others, and in one of the jovial scenes, he’s teased for his “tight-ass 1940s slang.” But he sees through the white-dominated power structure, which leads him to question why a genius like Cooke is working so hard to please white audiences, and why he isn’t doing more to help the movement.

Their debate is politically charged and full of “small” but fascinating details. Driving an orange-pink Corvette Stingray, Cooke makes a compelling case for a black man’s potential corporate power, for making progress from within the system. Cooke, charged implicitly with cooptation, defends himself by reminding his comrades that he started a record label that has launched the careers of many Black artists. He is quick to points out that, when he licensed Bobby Womack’s “It’s All Over Now” to the Rolling Stones, Womack was enraged–until he started seeing the fat royalty checks.

Jim Brown talks about playing a role in a Hollywood Western, “Rio Conchos.” He doesn’t consider himself a hero, telling Clay, “We’re just gladiators, man.” But then Malcolm X hits them with his insurgent view, summed up by the notion that African-Americans are dying every day. The struggle has always been there, but now the fight has arrived. He plays the iconic Bob Dylan song, “Blowin’ in the Wind,” and wonders how a white boy from Minnesota was writing more relevant protest music than Sam Cooke?

The movie in not nostalgic, it exists in the present, feeding off a crucial moment of transition. Inevitably, there is a sense of doom and dread while watching the characters , because we are informed by our hindsight knowledge of their fates. Our viewing is shadowed by the fact that Malcolm X would be assassinated in February of 1965, and that Sam Cooke would be shot in a Los Angeles motel altercation in November of 1964.

King ends the story with a rendition of Cooke’s “A Change Is Gonna Come,” a song that remains as hauntingly relevant to our current moment as it was half a century ago. Changes do occur in American history, but they don’t just happen. Among many merits, One Night in Miami offers some glimpses of how those changes might have begun and what they would look like in the future.

Being a trailblazer

As the first black female director to be accepted into Venice has put extra-pressure of “wanting this to do well, wanting it to be-well received so that you can open doors for other women like you.” King admits to be thinking about the responsibility that comes with being the first: “I’m trying to figure out where to put my emotions. The fact that in 2020 this is a first in a festival that’s been happening for 77 years, and I can think of so many good films by other black women filmmakers that I had just assumed were at Venice. I didn’t even realize they were not included, so I understand the responsibility. I do recognize that there’s a lot of pressure that goes on being firsts for anyone, or the second, third, fourth.”

Prior to the first showings, King was a bundle of nerves, and for good reasons: “We didn’t have time for any test screenings, so nobody knew how it would play with audiences. We were hoping for positive feedback, the kind that we’re getting now from festivals viewers in Venice and Toronto. We’re just living vicariously through the audience.”

There’s already Oscar buzz in town that King, who is 50, may break yet another important barrier. She may become the first black woman, and the only sixth woman, in the 92- year-history of the Academy Awards, to be nominated for the Best Director Oscar.