Cannes Film Fest 2014–There was high anticipation in Cannes Film Fest this year for the world premiere of Gabe Polsky’s documentary, Red Army, due to its subject matter and also due to the fact that its executive producer is the estimable Werner Herzog.

Cannes Film Fest 2014–There was high anticipation in Cannes Film Fest this year for the world premiere of Gabe Polsky’s documentary, Red Army, due to its subject matter and also due to the fact that its executive producer is the estimable Werner Herzog.

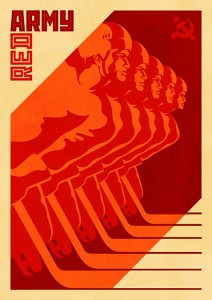

Though nominally a sports docu by subject and genre, the topic of Red Army is so encompassing that it covers broader issues well beyond the sports world, such as politics and propaganda. We get a sense of the ways in which the Soviet Union and later Russia continue to revise its collective history, both past and present.

As is known, the Soviet Union dominated the field of ice hockey during the Cold War. Among other things, the political regime used the team as evidence that communism, despite what the Western world thought, was an effective and satisfying system.

Unlike sports in most capitalistic countries–the U.S. is prime example–which is dominated by the star system, the Soviet hockey players represented a collective team, with presumably no celebrated individual stars, and all committed to their larger national goals.

As was the case of other fields of sports (and art and music), Soviet officials selected carefully young children and then place them in boot camps where, to put it bluntly, they were brain-washed with the values of dominant ideology. Time and again, the players were encouraged to believe that their highest goal was “to beat the West.”

As was the case of other fields of sports (and art and music), Soviet officials selected carefully young children and then place them in boot camps where, to put it bluntly, they were brain-washed with the values of dominant ideology. Time and again, the players were encouraged to believe that their highest goal was “to beat the West.”

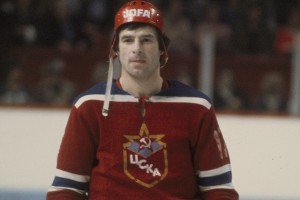

That said, I think director Polsky made a shrewd decision to focus on one player, Viacheslav ‘Slava’ Fetisov. A Red Army recruit from the age of 8, Fetisov enjoyed a long career that spanned several turning points in his country’s history. And it is through Fetisov’s sports career that we get insights into his country’s history and its place vis-a-vis the rest of the world.

Fetisov was a member of the team that lost to the U.S. during the Miracle on Ice at the 1980 Olympics. He became one of the first players to play in NHL after the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the introduction of Gorbachov’s glasnost policy. His career reached its climax when he was appointed Minister of Sport by Vladimir Putin, serving in this position until 2008. He is now a member of the Federal Assembly of Russia.

Fetisov was a member of the team that lost to the U.S. during the Miracle on Ice at the 1980 Olympics. He became one of the first players to play in NHL after the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the introduction of Gorbachov’s glasnost policy. His career reached its climax when he was appointed Minister of Sport by Vladimir Putin, serving in this position until 2008. He is now a member of the Federal Assembly of Russia.

Once a proud citizen of the Soviet Union, committed to both sports and country, he got disenchanted with the restrictive Soviet regime, represented to a large degree by his rigid and imposing coach, which may explain how he got seduced by the rewards (money included) of the America Way.

Problem is that the skills that made the Soviets players distinguished, such as teamwork, collectivism, and cooperation, were not valued by–in fact, they ran contrary to–the highly individualistic American sport, which has always emphasized ruthless competition, personal winning, and charismatic personality, which go beyond professional skills per se. Indeed, as the group members began to separate, they started to decline; they seemed to have been lost. “When they had the puck they shot,” says Fetisov. “For us the puck-holder was a slave to the rest of the team.”

Problem is that the skills that made the Soviets players distinguished, such as teamwork, collectivism, and cooperation, were not valued by–in fact, they ran contrary to–the highly individualistic American sport, which has always emphasized ruthless competition, personal winning, and charismatic personality, which go beyond professional skills per se. Indeed, as the group members began to separate, they started to decline; they seemed to have been lost. “When they had the puck they shot,” says Fetisov. “For us the puck-holder was a slave to the rest of the team.”

The Soviet hockey’s success in the NHL was the Detroit Red Wings victory at the 1997 Stanley Cup. Remarkably, the coach Scotty Bowman had built an old-fashioned Soviet team in the midst an American sports franchise.

Speaking of coaches, we meet the team’s first coach, Anatoli Saratov, credited with applying lessons and techniques from ballet and chess to bear on a sport that was largely known for its boxing moves. Viktor Tikhonov, the team’s next coach, was a rigid man, who came into conflict with Fetisov, then a top player with strong bargaining power.

The docu’s director is just as colorful as his subjects. The son of Russian immigrants, Polsky was raised in L.A., and this dual cultural background has certainly benefited his documentary. Throughout, in both text and subtext, he highlights the contrasts between the Russian and American value systems, which go way beyond the specificity of hockey.

Some of the interviewees are extremely harsh in their approach to Polsky, claiming that he asks the “wrong” questions, using dumb cultural clichés, and so on. At one funny point, Fetisov even gives him the finger! And throughout the on camera interview, the reluctant subject keeps looking at his cel phone

As a filmmaker, Polsky seemed to have been influenced by the strategies (and personality) of his eccentric and feisty executive producers, Werner Herzog and Jerry Weintraub–he is determined, committed, unfazed, and unembarrassed–no matter what the circumstances are–seizing on the dark humor (intentional and unintentional) of the context in which the docu was made, and grasping all the ironies involved in the process.

Did I mention that, along with being informative and insightful, Red Army is vastly entertaining?