Persona, Ingmar Bergman’s enigmatic, complex film, was the second Best Picture winner from the National Society of Film Critics, back in 1967. (The first winner was Antonioni’s Blow-Up).

One of Bergman’s most enduring masterpieces, Persona (made in 1966 but released later in the US) occupies a special position in the Swedish maestro’s spectacular career, which lasted half a century, and was defined by great films made almost up to his death, in 2012.

It is a key film (and art) work that blends the conventions of theatricality, psychodrama, and meta-cinema, indicating like no other feature before the inherent possibilities of film as a unique and distinctive medium.

In 1965, Bergman became extremely ill after contracting pneumonia and antibiotic poisoning. The director claims that the inspiration for Persona came to him while he was in the hospital. Elsewhere, Bergman had suggested that the film was born out of his personal desperation, calling it “a creation that saved its creator.”

Shooting began in July of 1965, though Bergman was still so sick that he could not stand without becoming dizzy. The film was released in Europe in 1966, and in the US a year later

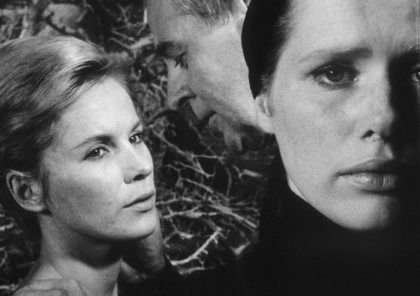

Nominally, Persona is “about” the ever-shifting relationship between two women: a celebrated stage actress named Elisabeth Vogler (Liv Ullmann), who has suffered a nervous breakdown and lost her speech after a performance of “Electra,” and the nurse in charge of taking care of her, Alma (Bibi Andersson).

In the course of the tale, Alma’s own anguish, troubled identity, and insecurity are unleashed by the mysterious woman in her care.

The tale unfolds as an intense psychodrama, in which the nurse does all of the talking, pouring her soul out to her patient, who remains silent for most of the time. Elisabeth reacts arbitrarily, only when she wants to, or when she is threatened or attacked by Alma, verbally or physically. With the exception of a few words, which Elisabet utters (or presumed to utter), her reactions consist of a limited repertoire of facial and body gestures.

Gradually, we get the notion that, both as a woman and as a professional, Alma might be more disturbed than her patient, whose personality she begins to assume, consciously, subconsciously and unconsciously.

As Alma “speaks” for both of them, she might be descending into a peculiar mode of madness, with manifestations of mental illness that’s hard to label, categorize, or rationally understand.

The two women, who physically look alike, begin to merge, though it’s Alma who undergoes the more extreme and overt transformation. Is Bergman suggesting that the two femmes represent two facets of one divided personality, or perhaps that they are–and remain to be to the bitter end–two separate women, defined by the dynamics of fluid and shifty personality. The film raises all kinds of issues regarding identity and personality.

Bergman and his skillful cinematographer emphasize the aforementioned notions by positioning the two women in front of the looking-glass mirror, as much observing themselves as the mirror (and we viewers) observing them.

Two major themes of this richly densely text concern the fragile, flexible nature of role-playing, as rigidly prescribed by society and then redefined and reinterpreted more subjectively by individuals, based in their needs, desires, and whims.

Alma and Elisabeth crisscross identities after engaging in brutal games of power and battles for control over each other. Who is stronger and who is more troubled? Alma, the professionally trained woman, officially in charge due to her uniformed position of authority? Or the seemingly needy, dependent, and catatonic Elisabet, the patient placed under Alma’s charge?

Bergman once said that Persona asks the metaphysical question of, “What is true, and when and how does one tell the truth, if there is such a thing”?

All of this suggests why critics have now spent five decades arguing over the “meanings” of Persona, a rare film that cineastes and historians feel compelled to revisit periodically, to validate their own interpretations against those of their colleagues.

Persona has become a notable phenomenon due to its various achievements and novelties: the use of film within film devices; the eerie yet erotic charge of the two women’s agonized relationship; the super-imposition of images, which at times suggests the protagonists’ psychic dissolution, and at other times implies their convergence.

One of Bergman’s scholars, Peter Cowie, has suggested that, “Everything one says about Persona may and can be contradicted; the opposite will also be true.” Bergman himself has said that he wanted the spectators to provide their own mental and psychic fantasies to fill the (blank) spaces that he created.

For the critic John Simon, Persona is still “the most difficult film ever made.” Other interpreters have dwelled on the meaning of specific scenes. The New Yorker critic Pauline Kael cites the sequence on the island, in which Alma recalls an orgy in which she had participated as a younger woman as “one of the rare truly erotic sequences in movie history.” P. Adams Sitney calls “the moment near the middle of Persona, when the film stock rips (or seems to rip) and burns, as “the greatest visual shock in all of Bergman’s often startling oeuvre.”

No matter the specific reading of the film, most scholars consider Persona to be one of Bergman’s masterpieces, precisely because of the work’s complex, ambiguous, multi-level narrative (whose synopsis I try to describe below).

Though a personal-auteurist work, there is no denying that Persona owes much of its disturbing effect, intense emotional impact, and lingering visual imagery to the splendid performances of Liv Ullmann and Bibi Andersson, superb actresses that are linked intimately to Bergman’s past and future output. Ullmann, who had a lengthy romantic affair with the director, gave birth to their boy.

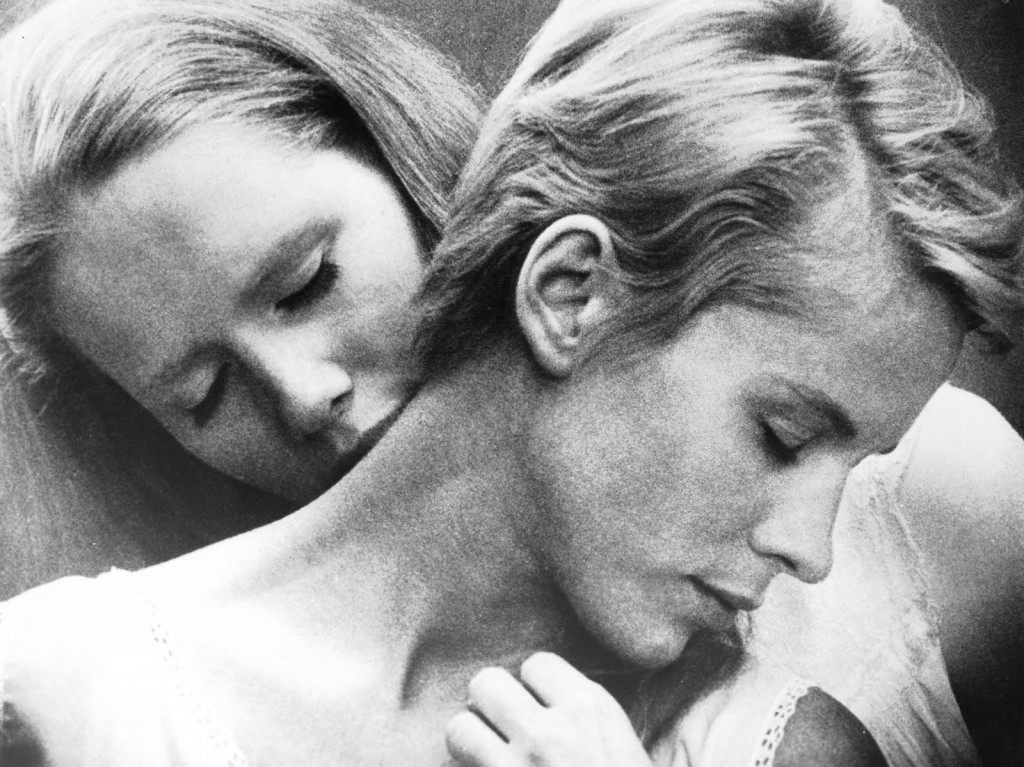

Even critics who don’t get the film–and dismiss it as an intellectual puzzle–would have to acknowledge the beauty and intensity of the faces of the two actresses. Near the end, the shot in which the two faces merge is one of the most luminous and poetic images in cinema’s history.

Here is a film that not only encourages but also requires multiple viewing. I saw the film for the second time in an Andrew Sarris class at Columbia University in the 1970s. My only disagreement with Sarris, who is the greatest American film critic ever–is his view that Persona is more incomplete than a puzzle, and that the film (and his creator) were slightly perverse in their denial of spectatorial pleasures.

I beg to disagree: Five decades after it was made, Persona continues to offer numerous pleasures–thematic, visual, philosophical, and performances–reaffirming one’s belief in the power of cinema.

Narrative Structure

The first segment is particularly rich and complex, a montage showing how films are actually made. We observe camera equipment and projectors as they light up and project brief images of a crucifixion, an erect penis, a tarantula spider, followed up by clips from a silent comedy-film depicting a man trapped in a room and chased by Death and Satan, and the slaughter of a lamb.

Bergman then switches to a young boy, who wakes up in a hospital, surrounded by corpses, and reading Mikhail Lermontov’s A Hero of Our Time. The boy then caresses a blurry image that shifts between Elisabet and Alma’s faces, in what becomes the film’s visual and thematic motif (see photo).

A young nurse named Alma (Andersson) is summoned by the chief doctor, who assigns her to take care of a famous stage actress named Elisabet Vogler (Ullmann), who has become mute under some strange and mysterious circumstances.

The hospital administrator (Margaretha Krook) offers her own seaside cottage as a place for the recovery of Elisabet. In her hospital room, the catatonic Elisabet reacts with panic upon seeing on her TV screen the image of a Vietnamese Buddhist monk burning himself to death, while Alma listens to her soap opera on the radio.

Upon leaving the hospital together, Alma reads aloud a letter that Elisabet’s husband had sent to her, which includes a photo of their young son, which may (or may not) explain the image of the boy in the beginning.

At the cottage, Elisabet begins to relax, though she remains quiet, silent and non-responsive. To pass the time and break the silence, Alma speaks constantly, at first about trivial matters, then about more personal matters, such as her own anxieties. She relates how her fiancé, Karl-Henrik, scolded her for not being ambitious enough, not so much with her career, as ”in some greater way,” as she puts it. Clearly, Alma is involved in a problematic bond with a man she may (or may not) love.

Growing insecure, Alma develops a peculiar, unhealthy (to say the least) emotional bond with Elisabet, based on comparisons with her, as well as attachment, criticism, and outright rejection. Their evolving relationship goes way beyond the norms of what’s expected of a nurse-patient interaction.

In one of the film’s most disturbing sequences—this is 1966, after all–Alma confesses in a long monologue how she cheated on her fiancé in a ménage à quatre with three underage boys on the beach. In a flashback, Bergman shows in graphic detail the sexual act, carried out with Alma’s consent, perhaps even her encouragement, though there is not much visible pleasure during (or after) the intercourse.

When she became pregnant, she asked Karl-Henrik’s friend abort the baby, but she is still struggling mentally with her action. Elisabet is heard saying, “You ought to go to bed, or you’ll fall asleep at the table.” But Alma dismisses it as a dream and Elisabet denies to have spoken.

Alma drives into town, taking Elisabet’s letters for the post office. She suddenly parks by the roadside and begins to read what Elisabet has written. To Alma’s dismay, she finds out that Elisabet has been studying, analyzing, and criticizing her. Back home, the distraught Alma accidentally breaks a glass, but she leaves the shards on the floor, hoping that Elisabeth would trip over them.

When Elisabet’s feet bleed from the cuts, she stares at Alma intensely. Shortly thereafter, the film stock itself breaks apart, and the screen turns into white. There are scratches on the images, which are accompanied by screeching sounds. The film unwinds as brief snippets of the prelude reappear.

When the film resumes, Elisabet looks out the window before walking outside to meet Alma, who is angry and bitter. Alma is hurt by the way that Elisabet has talked behind her back. Alma begs her to speak, and when Elisabet does not, Alma chases her through the cottage. Elisabet then hits her, causing Alma’s nose bleeding. In retaliation, Alma grabs a pot of boiling water off the stove and is about to fling it at Elisabet, but stops after hearing Elisabet screams, “No!”

Alma goes to the bathroom, trying to pull herself together. Frustrated by Elisabeth’s defiance and unresponsiveness, Alma lets her steam off: “They said you were healthy, but your sickness is of the worst kind: it makes you seem healthy. You act it so well everyone believes it, everyone except me, because I know how rotten you are inside.” Elisabet tries to walk away, but Alma continues to accost her. When Elisabet flees, Alma begs for forgiveness. That evening, Elisabet opens her book to find inside a Stroop Report photo of Jews arrested in the Warsaw Ghetto. Elisabet stares intensely at the image of a young boy raising his arms.

Alma watches Elisabet sleep, analyzing her face and the scars she covers with makeup. Outside, Elisabet’s husband, Mr. Vogler (Gunnar Björnstrand) mistakes Alma for his wife. Despite her repeated claim, “I’m not your wife,” he declares his love for her and their son (repeating words he wrote to Elisabet–“We must see each other as two anxious children”).

Alma admits her love for Mr. Vogler and accepts her role as the mother of Elisabet’s child. The two make love while Elisabet sits quietly with a look of panic.

The next morning; Alma sees Elisabet holding a picture of a small boy. Alma then narrates Elisabet’s life story back to her, while the camera focuses tightly on Elisabet’s anguished face. At a party, a man tells her “Elisabet, you have it virtually all in your armory as woman and artist. But you lack motherliness.” She laughs, because it sounds silly, but the idea touches a nerve.

As the pregnancy progresses, she grows increasingly worried about her swelling body, responsibility to her child, the pain of birth, and the idea of abandoning her career. Everyone tells Elisabet that she has never been so beautiful, but Elisabet tries to abort the fetus. After the child is born, she is repulsed by it, and prays for her son’s death. The child grows up tormented and desperate for affection.

The camera turns to show Alma’s face, and she repeats the same monologue again. At its conclusion, one half of the face of Alma and the other of Elisabet’s are shown in split screen–hey have become one face. Alma panics and cries “I’m not like you. I don’t feel like you. I’m not Elisabet Vogler: you are Elisabet Vogler. I’m just here to help you!”

In a dreamlike sequence, Alma, dressed in nurse’s uniform, goes to Elisabet and tells her to say “nothing.” Elisabet then repeats the word.

When Alma returns, Elisabet is completely catatonic, motivating Alma to beat her. Alma then packs and leaves the cottage alone, and Bergman turns away from the women to show the crew shooting the scene.

In the film’s last image, the tale goes circular and we see the boy from the prologue touching the split-screen image of Elisabet and Alma.

Cultural Status

Pauline Kael and her negative review must have been in minority for in 1967 Persona won the awards of the National Society of Film Critics (NSFC, then in its second year) for Best Film, Best Director (Bergman) and Best Actress (Bibi Andersson). As a voting member of this group (since 1991), I know that it’s very rare for a single film to sweep three major awards.

In 2010, the film was ranked as #71 in Empire magazine’s survey of “The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema.”

The film was submitted as the Swedish entry for the Best Foreign Language Film Oscar, but was not accepted as one of the five nominees.

About Bergman

Bergman was born in 1918 in Uppsala, Sweden. His pastor father ingrained in him the basic concepts that would later resurface in his films: sin, confession, punishment, forgiveness and grace. Bergman became a student of art history and literature at the University of Stockholm, then an errand boy at the Royal Opera House, and finally a filmmaker. His films include Wild Strawberries (1957), The Seventh Seal (1957), Cries and Whispers (1972), Scenes from a Marriage (1973), Autumn Sonata (1978) and Fanny and Alexander (1983). He also wrote Best Intentions (1992), which Bille August directed.

Credits:

Running Time: 81 minutes