In his 45th feature, Woody Allen joins a long list of distinguished filmmakers, headed by Hitchcock, who have examined the issue of the “perfect” murder. Unfortunately, his film is more ambitious in conception than execution, and is not sufficiently grounded in any recognizable reality (I will explain later).

In his 45th feature, Woody Allen joins a long list of distinguished filmmakers, headed by Hitchcock, who have examined the issue of the “perfect” murder. Unfortunately, his film is more ambitious in conception than execution, and is not sufficiently grounded in any recognizable reality (I will explain later).

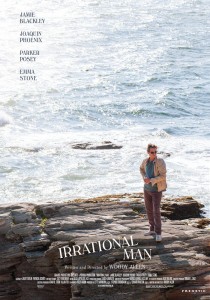

In its more serious theme and darker tone, “Irrational Man” continues Allen’s explorations in two previous–and better–pictures: “Crimes and Misdemeanors,” of 1989, and “Match Point,” a decade ago.

Commercial prospects

Commercial prospects are mediocre for a film that raises more questions than it can possibly answers, and is far less entertaining than recent comedies, such as the fluffy and shallow but also entertaining “Midnight in Paris,” or the fabulously-acted melodrama, “Blue Jasmine,” which was Woody Allen’s homage to Tennessee Williams’ “A Streetcar Named Desire.”

World premiering at the 2015 Cannes Film Fest, Irrational Man will be released on July 24 Sony Classics release as counterprogramming.

World premiering at the 2015 Cannes Film Fest, Irrational Man will be released on July 24 Sony Classics release as counterprogramming.

In a Cannes interview, Allen noted: “Since I was very young for whatever reason I’ve been drawn to what people always call the ‘big questions.’ In my work they’ve become subjects I kid around with if it’s a comedy or deal with on a more confrontational way if it’s a drama.”

Joaquin Phoenix, who is quickly becoming a quintessential actor of his generation, having worked with Spike Jonze in “Her,” and more recently with Paul Thomas Anderson in “Inherent Vice,” is well cast as Abe Lucas, a philosophy professor who’s appointed to a small Rhode Island college.

Joaquin Phoenix, who is quickly becoming a quintessential actor of his generation, having worked with Spike Jonze in “Her,” and more recently with Paul Thomas Anderson in “Inherent Vice,” is well cast as Abe Lucas, a philosophy professor who’s appointed to a small Rhode Island college.

I have been a university professor for over three decades but have never met anyone like Abe, an alcoholic academic, who drinks freely on campus grounds, and enjoys having affairs with his female students. Early on, we learn that Abe’s wife had recently left him for his best friend, and that he has observed the traumatic death of a friend killed by a land mine in Iraq.

The fictional Braylin College (actually Newport’s Salve Regina University) seems to be a liberal arts college so dormant and passive that it kind of eagerly awaits for (even expects) a man like Ave to arrive and stir some action and drama. And, boy, does Abe ever?

Behaving casually in the classroom, Abe tells his impressionable students that “much of philosophy is verbal masturbation.” Later on, he is seen playing Russian roulette in front of onlookers at an off-campus party.

Lacking the smooth flow of events in Allens’ good pictures, this tale relies not on one but on two voice-over narrations. Emotionally, I had arrived at Zabriskie Point,” Abe says, but it’s unclear whether he means what he says, or whether he understands the implications of his statement–if taken seriously.

Lacking the smooth flow of events in Allens’ good pictures, this tale relies not on one but on two voice-over narrations. Emotionally, I had arrived at Zabriskie Point,” Abe says, but it’s unclear whether he means what he says, or whether he understands the implications of his statement–if taken seriously.

Braylin’s female faculty and students seem sexually and/pr emotionally starved, judging by how they court and offer themselves to Abe. Take, for example, Jill Pollard (Emma Stone), a bright student in Abe’s summer “ethical strategies” class, who becomes more than intrigued by her professor, to the point of neglecting her own boyfriend.

Then there is the more mature (in age at least) Rita Richards (Parker Posey), an unhappily married professor who tries to seduce him over and over again until she succeeds. That Abe, who may suffer from impotence or depression (or both), is able to perform only after he commits murder, raises some unsettling issues about crime and (lack of) punishment.

The film’s livelier sessions are those depicting the growing affection between Abe and Jill, who ‘s trying to understand how and why a man who was once activist and relief worker Darfur and New Orleans, has lost interest not only in political activism but in life itself, reaching a point of unexplainable passivity.

The film’s livelier sessions are those depicting the growing affection between Abe and Jill, who ‘s trying to understand how and why a man who was once activist and relief worker Darfur and New Orleans, has lost interest not only in political activism but in life itself, reaching a point of unexplainable passivity.

The main stimulus that pulls Abe out of his depression is accidental, a random conversation in the local diner, in which a desperate woman discusses her custody battle with a creepy husband and corrupt judge. Out of the blue, Abe decides to dispose of the judge in a seemingly “perfect” murder, in broad daylight at a public park (no more can be revealed). His overt motivation is to make the world a better place to live, but there is something else going on a deeper, perhaps subconscious or unconscious level.

The main stimulus that pulls Abe out of his depression is accidental, a random conversation in the local diner, in which a desperate woman discusses her custody battle with a creepy husband and corrupt judge. Out of the blue, Abe decides to dispose of the judge in a seemingly “perfect” murder, in broad daylight at a public park (no more can be revealed). His overt motivation is to make the world a better place to live, but there is something else going on a deeper, perhaps subconscious or unconscious level.

Unlike Hitchcock’s villainous murderers, Abe is inexperienced and makes a series of fatal mistakes, such as visiting he college’s lab to inquire about different kinds of poisons and getting spotted there by one of his students.

Unlike Hitchcock’s villainous murderers, Abe is inexperienced and makes a series of fatal mistakes, such as visiting he college’s lab to inquire about different kinds of poisons and getting spotted there by one of his students.

The movie is replete with references to Kierkegaard, Freud, Dostoevsky, Heidegger, Kant, Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, most of which amount to name-dropping, contained in a rather shallow effort to explain or understand behavior in philosophically existential terms.

Spoiler Alert

The notion of murder arouses Abe not only intellectually but also emotionally and sexually. After the killing, which for a while goes well and undetected, there is no more creative block, no more erotic problems.

The notion of murder arouses Abe not only intellectually but also emotionally and sexually. After the killing, which for a while goes well and undetected, there is no more creative block, no more erotic problems.

Allen has said that his movie’s title is inspired by a 1958 volume by philosopher and literary critic William Christopher Barrett, which sought to explain existentialism in simpler ways.

Credits

Running time: 94 Minutes.

Directed, written by Woody Allen.

Camera (Fotokem, Panavision widescreen), Darius Khondji

Editor, Alisa Lepselter

Production designer, Santo Loquasto

Art director, Carl Sprague

Costume designer, Suzy Benzinger

Sound, David J. Schwartz