“Distant Voices, Still Live,” made in 1988, is arguably one of the jewels in the crown in Terence Davies’s oeuvre. As such, it indicates the problems of a filmmaker who begins on a very high note, and then struggles to match that achievement. Davies has done it just once, with the sublime documentary, “Of Time and the City.”

Davis has described “Distant Voices” as “an homage to my mother and to my family.” Part warm nostalgia, part cold nightmare, part painful memoir and satisfying on each of these levels, “Distant Voices, Still Lives” offers a bittersweet look at Davies’ working-class upbringing in post-WWII Liverpool. “Distant Voices, Still Lives” is essentially a dramatic musical, or a musical drama, a rare sub-genre in American cinema. Indeed, the film is made against the grain of most Hollywood musicals, past and present, which are joyous, upbeat, and boisterous.

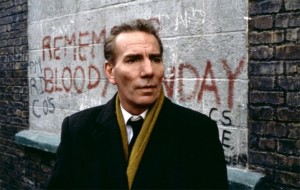

The film’s title reflects the narrative structure, which is divided into two segments, equal in length and shot apart from each other. The dense, multi-layered narrative provides a portrait of a house ruled by a tyrannical father, Tommy Davies (Peter Postlethwaite), a man given to erratic bursts of temper, ranging from deep love and compassion to brutal physical abuse. Significantly, no explanation is offered for Tommy’s schizoid personality.

The film’s title reflects the narrative structure, which is divided into two segments, equal in length and shot apart from each other. The dense, multi-layered narrative provides a portrait of a house ruled by a tyrannical father, Tommy Davies (Peter Postlethwaite), a man given to erratic bursts of temper, ranging from deep love and compassion to brutal physical abuse. Significantly, no explanation is offered for Tommy’s schizoid personality.

For example, a crucial Christmas scene begins with a tracking shot of a row of similar houses. Accompanied by choral music, the camera goes into the house, where the father is decorating the Christmas tree. He says good night to his children, and later makes sure they are sound asleep (they’re all crammed in one bed). “God bless, kids,” Tommy whispers before placing a stocking to their bedpost. In the next scene, the family is gathered for Christmas dinner, and as usual, father Tommy claims his seat at the head of the table. Then, without any warning, his fingers begin to tremble and his whole body shakes up. He pulls off angrily the tablecloth with all the dishes and food, while yelling at his wife, “Clear this up!” This two-minute sequence captures the erratic conduct of an alcoholic patriarch, subject to contradictory impulses, goings from extreme tenderness to uncontrollable brutality.

For example, a crucial Christmas scene begins with a tracking shot of a row of similar houses. Accompanied by choral music, the camera goes into the house, where the father is decorating the Christmas tree. He says good night to his children, and later makes sure they are sound asleep (they’re all crammed in one bed). “God bless, kids,” Tommy whispers before placing a stocking to their bedpost. In the next scene, the family is gathered for Christmas dinner, and as usual, father Tommy claims his seat at the head of the table. Then, without any warning, his fingers begin to tremble and his whole body shakes up. He pulls off angrily the tablecloth with all the dishes and food, while yelling at his wife, “Clear this up!” This two-minute sequence captures the erratic conduct of an alcoholic patriarch, subject to contradictory impulses, goings from extreme tenderness to uncontrollable brutality.

With his detached approach, Davies avoids the cliched nostalgia and romanticism, which often characterize autobiographical movies. Placed against John Boorman’s 1987 humorous but sentimental memoir about growing up at the same time, during WWII, the Oscar-nominated “Hope and Glory,” the differences between the two renditions become immediately apparent.

A stylized portrait, “Distant Voices” is nominally plotless. It consists of several impressionistic set-pieces, presented out of order, in a non-linear mode. Told in flashbacks, the film begins and ends with family weddings, held several years apart, during which the grown-up children reflect on their father and his impact on their lives. Though Davies’ look is uncompromisingly harsh, the film is imbued with unmistakable humanism, an approach that refuses to see real life as just a gloom and doom experience. The characters’ daily lives, Davies suggests, may be static and rough, but they are certainly not dull or conventional. His subtle observations form a compellingly coherent, visually vividly, and emotionally powerful memoir. Though subjective and fragmented, Davies’ portrait bears the kind of timeless resonance that speaks to viewers who grew up in different circumstances than his own.

A stylized portrait, “Distant Voices” is nominally plotless. It consists of several impressionistic set-pieces, presented out of order, in a non-linear mode. Told in flashbacks, the film begins and ends with family weddings, held several years apart, during which the grown-up children reflect on their father and his impact on their lives. Though Davies’ look is uncompromisingly harsh, the film is imbued with unmistakable humanism, an approach that refuses to see real life as just a gloom and doom experience. The characters’ daily lives, Davies suggests, may be static and rough, but they are certainly not dull or conventional. His subtle observations form a compellingly coherent, visually vividly, and emotionally powerful memoir. Though subjective and fragmented, Davies’ portrait bears the kind of timeless resonance that speaks to viewers who grew up in different circumstances than his own.

In his unflinching search for truth, Davies shows understanding for all of his characters. The distinguished actor Pete Postlethwaite (Oscar-nominated as Daniel Day-Lewis’ father in Jim Sheridan’s 1993 social injustice drama, “In the Name of the Father”) plays Tommy Davies, the violent taciturn father, and Freda Dowie is his suffering yet stoic wife. Angela Walsh is Eileen, the daughter whose marriage offers some promising change if not complete freedom from a life of misery.

In his unflinching search for truth, Davies shows understanding for all of his characters. The distinguished actor Pete Postlethwaite (Oscar-nominated as Daniel Day-Lewis’ father in Jim Sheridan’s 1993 social injustice drama, “In the Name of the Father”) plays Tommy Davies, the violent taciturn father, and Freda Dowie is his suffering yet stoic wife. Angela Walsh is Eileen, the daughter whose marriage offers some promising change if not complete freedom from a life of misery.

Davies transcends the dreariness and misery of his mood piece by creating a work in which music serves as direct expression of emotions. The musical numbers are lyrically stylized statements of feelings. The opening number consists of a languid tracking shot through an empty dark-green living room, as “I Get the Blues When It Rains” plays in the background. It then dissolves into a medium shot of the main characters: Mother (Freda Dowie) and her grown children, Eileen (Angela Walsh), Maisie (Lorraine Ashbourne), and Tony (Dean Williams). Clad in black and positioned in a spare tableau, they suggest figures in a faded family album.

Davies transcends the dreariness and misery of his mood piece by creating a work in which music serves as direct expression of emotions. The musical numbers are lyrically stylized statements of feelings. The opening number consists of a languid tracking shot through an empty dark-green living room, as “I Get the Blues When It Rains” plays in the background. It then dissolves into a medium shot of the main characters: Mother (Freda Dowie) and her grown children, Eileen (Angela Walsh), Maisie (Lorraine Ashbourne), and Tony (Dean Williams). Clad in black and positioned in a spare tableau, they suggest figures in a faded family album.

The emotional power of Davies’ fractured and elliptical family chronicle is undeniable. The first part, “Distant Voices,” revolves around the painful memories of childhood, defined by fear and wartime suffering. As a boy, he is the product of repressive Catholic childhood. The second, “Still Lives,” portrays the slightly happier life of a widow, her daughters and sons, and their friends. They gather in pubs, sing collectively, begin to live–and also suffer from–their own lives. The songs they sing together include popular tunes like “Buttons and Bows,” “That Old Gang of Mine,” and “Bye-Bye Blackbird.” But Davies makes sure to include some specifically-ethnic songs, such as the Jewish “My Yiddisher Mama,” the Irish “When Irish Eyes Are Smilin’,” and the black “Brown-Skinned Girls.”

The marriages of Eileen, Maisie, and their friend Micky signify solidarity with one another, and hope, based on their innocent belief that their unions would differ from those of their parents. Nonetheless, from the start, Eileen’s marriage threatens to follow the same tragic pattern of her mother’s. In the pub, right after her wedding, Eileen sobs into the arms of her husband George, fearfully crying, “I Want Me Dad!” Later on, feeling the patriarchal tyranny in her own marriage, Eileen rebelliously sings, “I Want to be Around to Pick Up the Pieces,” a personal response to her own domineering husband.

Davies’ family life is evoked through subjective recollections. His poetic narrative drifts in and out of reality, suggesting the prevalence of ghosts and demons of the past. The film offers tension between the public solidarity, reflected in pub sing-a-longs, wedding, and mournings, and the private horror of domestic abuse, depression, and unfulfilled dreams.

Like Almodovar and Haynes, Davies’s empathy resides with the women. The men are flawed or damaged goods. The husbands of Eileen and Maisie seem to be variations of Tommy, the rigid father. ”They’re all the same,” Micky remarks, “When they’re not usin’ the big stick, they’re fartin’.” Though they are the heroines of the piece, the women are creatures of compromise. “Why did you marry him, mom?’ asks one daughter. “He was nice, and he was a good dancer,” the mother replies.

Memory is intensely linked to music from Davies’s childhood. Each snippet heard is connected to a specific emotional experience of the past. “Taking a Chance on Love” is heard while the Mother sits on a windowsill polishing the glass from the outside, a lyrical moment placed against the drab milieu. Davies then cuts from the kids watching Mother by the window to her being brutally beaten by Father, but he lets the same music play, as he shifts from a fondly recalled moment to a traumatic one.

Dramatically, it seems that the main purpose of Tony’s going AWOL as a soldier is to offer an occasion for a willful confrontation between father and son. The scene begins with Tony smashing a front window with his fist, and ends when he is arrested by the Military Police and thrown into prison. Yet, while locked in the brig, Tony pulls out his harmonica and plays the melodic theme from Charlie Chaplin’s 1952 “Limelight.”

In one of the film’s striking moments, Tony and George (Vincent Maguire), who’s Eileen’s husband, are observed in an overhead shot as they are falling together in slow motion through the same skylight. Both men have suffered work-related accidents that send them to the hospital, yet only George’s fall from the scaffold is shown on screen.

There are moments of comic, even surreal relief. When Maisie and her husband Dave (Michael Starke), who live with her grandmother, are having dinner together, the door suddenly opens and a man (a pale version of the father) appears with a candle. “I switched the light off,” he says, “but I don’t know whether I’m doing right or wrong.” After leaving, Dave asks, “Who was that man?” Maisie simply says, “Uncle Ted.” A moment later, the real Uncle Ted and his candle are shown as he is stopped at the stairs by his grandmother. “Teddy,” she reproaches,“ stop acting soft!” She then blows out the candle.

The narrative is restricted to a few limited, mostly interiors locations like the living room, the kitchen, the staircase, the children’s bedroom. The outdoor scenes take place in the stable (the father’s work space), the hospital ward, the church, and, most important all, the neighborhood pub. The confinement of the characters to specific areas highlights the prevalent sexual segregation and also intensifies the film’s emotional impact. Women in the pub often sit by themselves and sing together in joyous moments interrupted abruptly, when the men are done discussing sports and wish to leave the party right away.

The area in front of the house is a particularly significant space since it’s neither indoors nor outdoors, though sometimes it functions as both, literally and figuratively. It is a place of relative relaxation, an escape from the internal and external oppression. Eileen, Maisie, and Micky go out there to smoke, whereas other family members use the space for much needed fresh air during shared events. After his own wedding, Tony is seen crying in front of the house, which captures a rare moment of aloneness, as the family is large and there are also gatherings. Though the interiors are cramped settings like bomb shelters, the characters reach out and connect through music, while their feet remain firmly in the ground. Performing songs represent a fleeting, defiant ecstasy, a revolt against the crushing oppression.

“Still Lives,” the film’s second half, doesn’t make the same intense emotional demands on its viewers as “Distant Voices.” Once the father dies, the film loses its dramatic momentum and narrative urgency, though it still offers plenty of events, both highs and lows, of the family folklore. The tale concludes on a lovely note, showing Tony’s wedding and then the participants’ departure, establishing an elegiac tone.

Davies has said that he deliberately divided the film into two contrasting halves, each made with different crews over a two-year phase. “Distant Voices” has pale-sepia tones, while “Still Lives” abounds in ethereal fades to white. Painterly stillness alternates with gliding camera movement. Bleak darkness prevails, from the imagery of the dreary cramped rooms and sunless hallways, to black alleys, pubs and bomb shelters, lit only by pale rays. The little color that exists in these lives is reflected in the old photographs, which overtime have faded into yellowish brown.

“Distant Voices, Still Lives” stands in sharp opposition to the Technicolor glory and upbeat mood of the MGM fantasy-musicals of the era, such as Vincente Minnelli’s 1944 musical “Meet Me in St. Louis,” starring Judy Garland, or “American in Paris” and “Singin’ in the Rain,” starring Gene Kelly, musicals that Davies liked as a boy. But there are no glossy or glitzy set-pieces in his art as a mature man.

Films like “Distant Voices, Still Lives” are unfortunately treated and marketed by American distributors as depressing art works, but it’s a misconception. Through the songs’ physicality, and the women’s mixture of laughs and tears, Davies suggests that, despite the sorrow and grief, they–and we–should be grateful just to be alive. As an artist, Davies invites audiences to share in the suffering of his characters, which is realistic and grounded, but he also encourages them to participate in their ecstatic joy and happiness, fleeting and ephemeral as they may be.

Unlike Dennis Potter’s “The Singing Detective,” which is sardonic and bitter, Davies’ film is not ironic. Potter sees pop culture as the great divide, inevitably separating idealized fantasy from cruel reality. In contrast, Davies finds beauty, humanity, and salvation in the same British reality of sorrow and suffering.

Davies is a subject of my book:

About Terence Davies

Terence Davies is noted for his recurring themes of emotional and sometimes physical endurance, the influence of memory on everyday life and the potentially crippling effects of dogmatic religiosity on the emotional life of individuals and societies. Stylistically, Davies’ works are notable for their symmetrical compositions, “symphonic” structure and measured pace. He is also the sole screenwriter of all his films.

Davies went to the National Film School, and his trio of autobiographical works, known as The Terence Davies Trilogy have been screened at film festivals world-wide and have won numerous awards. Davies has directed five feature films to date firstly, Distant Voices, Still Lives and The Long Day Closes, two very autobiographical films set in 1940s and 1950s Liverpool.

His next two films were both adaptations, “The Neon Bible,” starring Gena Rowlands, and “The House of Mirth,” with Gillian Anderson. His most recent released work is the documentary, “Of Time and the City,” which premiered at the 2008 Cannes Film Festival to rave reviews.

He has produced two works for radio, “A Walk To The Paradise Gardens,” an original radio play broadcast on BBC Radio 3 in 2001, and a two-part radio adaptation of Virginia Woolf’s The Waves, broadcast on BBC Radio 4 in 2007.

Cast

Mother (Freda Dowie)

Father (Pete Postlewaite)

Eileen (Angela Walsh)

Maisie (Lorraine Ashbourne)

Tony (Dean Williams)

Eileen as a child (Sally Davies)

Tony as a child (Nathan Walsh)

Maisie as a child (Susan Flanagan)

Dave (Michael Starke)

George (Vincent MaGuire)