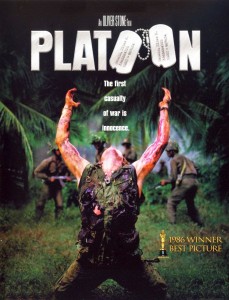

In 1986, when “Platoon” won the Best Picture Oscar, it seemed to many less an award for the movie’s artistic qualities than for its timely expression of the anxieties about Vietnam and the courage of the men who fought the (unpopular) War.

In 1986, when “Platoon” won the Best Picture Oscar, it seemed to many less an award for the movie’s artistic qualities than for its timely expression of the anxieties about Vietnam and the courage of the men who fought the (unpopular) War.Vividly based on Oliver Stone’s own experience in Vietnam, “Platoon” takes place in 1968. The film is told from the shifting point-of-view of a youngster named Chris (Charlie Sheen as Stone’s alter-ego), a green recruit and child of privilege who drops out of college and enlists into a tour of duty without knowing anything about Vietnam.

The opening scene is quite depressing, depicting the newcomers as they disembark from the transport plane, passing body bags about to be shipped back home. The bags contain the dead soldiers the greeners are replacing, an image that immediately suggests the loss of human life and the futility of the individual soldiers, who are now reduced to anonymous bodies.

As Chris wanders through ominous jungles, filled with unseen snipers, insects, and wild vegetation, Stone employs a direct and immediate approach to rub our noses into the “routine” combat experience, forcing us to see and hear the war as his central character does. Platoon won a well-deserved Oscar for Sound, orchestrated with great authenticity by a team of four technicians.

As Chris wanders through ominous jungles, filled with unseen snipers, insects, and wild vegetation, Stone employs a direct and immediate approach to rub our noses into the “routine” combat experience, forcing us to see and hear the war as his central character does. Platoon won a well-deserved Oscar for Sound, orchestrated with great authenticity by a team of four technicians.

In due time, the untested and inexperienced Chris finds himself forced to make a moral choice, dramatized by two sergeants vying for his soul and mind. On the one hand, there’s Sergeant Barnes (Tom Berenger), a facially and spiritually scarred combat vet who has survived the madness of jungle war by embracing an almost inhuman toughness and unrestrained violence. Barnes is contrasted with Sergeant Elias (Willem Dafoe), who’s also a good soldier and battle-hardened but one who somehow has managed to cling to a code of ethics that calls for decent human conduct, even in the face of an absurd and incomprehensive War like Vietnam.

Mixing reportage expose of the War with a more conventional morality play (the narrative strategy of all of his movies), Stone employs Barnes and Elias as realistically drawn soldiers as well as broader symbols for Good and Evil. Choosing between them thus becomes Chris’s crucial tactics not only to survive the War but also to save his soul more or less intact.

Mixing reportage expose of the War with a more conventional morality play (the narrative strategy of all of his movies), Stone employs Barnes and Elias as realistically drawn soldiers as well as broader symbols for Good and Evil. Choosing between them thus becomes Chris’s crucial tactics not only to survive the War but also to save his soul more or less intact.

Stone is a blatantly political filmmaker, an inclination that would become clearer with his next features, “Born on the Fourth of July,” “The Doors,” and “JFK.” Here, he almost unnecessarily interrupts the visceral proceedings with heavy-handed voice-over narration through letters that Chris writes home to his grandmother. The cumulative effect of Chris’s commentary is a message-driven picture in which every single idea, of Chris the character and Stone the writer, is spelled out.

Even so, “Platoon” overcomes its shortcomings with stunningly realistic depictions of the day-to-day combat. While uncompromisingly capturing the horror of death in combat, Stone leaves some ambiguity regarding the initial excitement of young men going to battle for the first time in their lives. Stone suggests that for some youngster, going to war was not only an avenue of escaping college and the clutches of parental authority, but also an opportunity to test their manhood in as series of rituals; what anthropologists call rites of passage.

Even so, “Platoon” overcomes its shortcomings with stunningly realistic depictions of the day-to-day combat. While uncompromisingly capturing the horror of death in combat, Stone leaves some ambiguity regarding the initial excitement of young men going to battle for the first time in their lives. Stone suggests that for some youngster, going to war was not only an avenue of escaping college and the clutches of parental authority, but also an opportunity to test their manhood in as series of rituals; what anthropologists call rites of passage.

Adding to the combat-ridden tension is the lack of assurance of how Chris will react to various conflicting situations. Like other soldiers, Chris shows a surprisingly quick adaptation to cruelty and violence in one moment, but then seconds later, decency and regret cause him to recoil from brutality.

Like the two sergeants, who function as distinct role models of soldiers and fathers, Chris is both a realistic and symbolic figure, conveying the torment between forces of light and darkness within himself, and by extension, within every soldier.

In some scenes, Stone draws on the rich tradition of combat movies, using generic conventions and stereotypical war movie situations only to undercut and criticize them. Hence, we expect a nice soldier to die when he jubilantly boards an early helicopter out, but the explosion never occurs. Like the men in the platoon, we’re never certain whether the village they are about to attack is actually a Viecong hideout. More importantly, we assume that decent teenager like Chris could never pull the trigger on his own noncom, but at the end, he blows away his superior.

In some scenes, Stone draws on the rich tradition of combat movies, using generic conventions and stereotypical war movie situations only to undercut and criticize them. Hence, we expect a nice soldier to die when he jubilantly boards an early helicopter out, but the explosion never occurs. Like the men in the platoon, we’re never certain whether the village they are about to attack is actually a Viecong hideout. More importantly, we assume that decent teenager like Chris could never pull the trigger on his own noncom, but at the end, he blows away his superior.

Eliminating the usual distance that prevails between viewers and onscreen activities, Stone wants us to feel as if we are members of the platoon, sharing Chris’s limited knowledge, fearing the first time he tastes combat, experiencing serious dilemmas about killing innocent civilians.

Though “Platoon” is a three-handler drama, the secondary characters are also fully fleshed out, including Keith David as a confused black recruit, and Kevin Dillon (brother of Matt Dillon) as a nasty wise guy.

Though “Platoon” is a three-handler drama, the secondary characters are also fully fleshed out, including Keith David as a confused black recruit, and Kevin Dillon (brother of Matt Dillon) as a nasty wise guy.

Cast

Sgt Barnes (Tom Berenger)

Sgt Elias (Wilem Dafoe)

Chris (Charlie Sheen)

Big Harold (Forest Whitaker)

Rhah (Francesco Quinn)Sgt. O’Neill (John C. McGinley)

Sal (Richard Edson)

Bunny (Kevin Dillon)

Junior (Reggie Johnson)

King (Keith David)

Running time: 111 minutes

Origins: Good Movies Come From…

After his tour of duty in Vietnam ended in 1968, Oliver Stone wrote a screenplay called Break, a semi-autobiographical account about his experiences with his parents and his time in the Vietnam War. Stone’s active duty service changed the way he viewed life and war. Although the script of Break was never produced, he later used it as the basis for Platoon.

Break featured some characters who were later developed in Platoon. The script was set to music from The Doors; Stone sent the script to Jim Morrison, hoping he would play the lead. Morrison never responded, but his manager returned the script shortly after Morrison’s death; Morrison had the script with him when he died in Paris. Although Break was never produced, Stone decided to attend film school.

After writing several screenplays in the 1970s, Stone worked with Robert Bolt on The Cover-up, which was not produced. Bolt’s rigorous approach inspired Stone, who used characters from Break and developed a new screenplay, which he titled The Platoon. Producer Martin Bregman attempted to elicit studio interest, but was not successful. However, based on the strength of his writing, Stone was hired to write the screenplay for Midnight Express (1978), which earned him the Best Screenplay Oscar.