The most iconoclastic American director, Robert Altman was the proudest survivor of many victories and defeats, devoting himself selflessly and effectively to moviemaking as a lifelong struggle for over half a century.

The epitome of maverick, controversial filmmaking, Altman has refused to play by the rules. Altman’s erratic career has progressed fitfully from the late 1950s, when his nonconformist reputation delayed his transition to features.

As Leo Braudy has observed, Altman built his entire career on attempts to reconcile basic contradictions of the industry: genre versus art film, popular and commercial directors versus serious and art-oriented ones.

Drawing on the energy of classic genres, Altman has brought an ironic, irreverent gaze to bear on traditional American values, showing fondness for loose, incongruous style. Unlike most Hollywood directors, he has never been a storyteller and is more interested in mood and ambience than in plot. A maverick auteur whose quirky, multi-layered films cast an astute, irreverent eye on American culture, Altman has rejected the well-made Hollywood movie in a spirit of innovation and commitment to a new way of seeing.

Raising a tiny budget from local sources, Altman produced, wrote and directed his first feature, The Delinquents (1957), an exploitation film about juvenile crime which he later sold to United Artists at a profit.

After collaborating with George W. George on the compilation-documentary film, The James Dean Story (1957), he found a niche as a TV director of episodes for series like “Bonanza” and “Alfred Hitchcock Presents.”

A full decade elapsed before he returned to feature films with Countdown (1968). Since then, he has directed some influential films like M.A.S.H. and Nashville, while revising popular genres: the detective thriller (The Long Goodbye), Western (McCabe and Mrs. Miller), love on the run (Thieves Like Us).

M.A.S.H.

Altman asserted himself as a front rank director with M.A.S.H. (1970), an iconoclastic anti-war black comedy, which won the Golden Palm at Cannes and the Best Screenplay Oscar (among other Oscar nominations) and became his most substantial commercial hit. Displaying what became his distinctive style of overlapping sounds and images, MASH was not so much about war as about the peculiarly American way of practicing War. He looked away from slaughter in favor of a detailed depiction of camp life.

After the film’s huge commercial success, Altman was flooded by studio offers for big-budget productions, but he typically chose Brewster McCloud (1970), a modest, whimsical allegory of limited marketability. It was the start of a career-long chasm between the stubbornly individualistic Altman and the Hollywood establishment.

His next few films, McCabe and Mrs. Miller (1971), Images (1972), Thieves Like Us (1974) garnered critical praise, but failed at the box office.

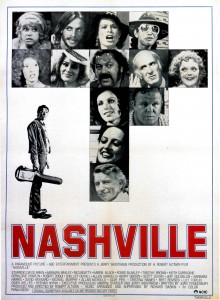

For the second–but not last time–in his career, Altman came back from the Hollywood dead with Nashville (1975), an inventive mosaic of the American experience composed of intricate interweaving of 24 characters. The film and Altman were nominated for Oscars, after being named best picture and director by the New York Film Critics.

Altman’s most ambitious film, Nashville, had a multi-layered narrative, a large ensemble, breezy speed, witty music, and overlapping dialogue. The feel of time and space, stretching to contain the actions of two dozens characters, all sharing equal time, all moving in random turmoil and coincidence, was original, innovative, and the ideal material for Altman.

Having regained Hollywood’s trust, Altman quickly squandered on the bizarre Buffalo Bill and the Indians (1976), Three Women (1977), and A Wedding (1978), which were varied, but again failed at the box-office. Quintet (1979) a tale of a future ice age.

In 1980, Popeye (1980), starring Robin Williams, a big-budget comic strip adaptation, failed to please either critics or audiences.

Throughout the 1980s, Altman ran into hard times with his reliance on theatrical material that seemed pedestrian after his 1970s work. Still, small-scale films, such as Come Back to the Five and Dime Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean, Streamers, Fool for Love, set the tone for an indie movement that targeted a more discerning audience. Come Back is well acted, though Altman couldn’t transcend the mediocrity of a sentimental play. Streamers was misconceived and didn’t live up to the original play, and Fool for Love failed to capture the drama’s intensity.

He suffers from a reputation of being arrogant, unpredictable and difficult.

The Hollywood establishment had written off Altman by the 1980s. Living in Paris, he worked on some theatrical adaptations: Secret Honor (1984), a monologue about Richard Nixon. His cable miniseries Tanner ’88 (1988), a political satire gained favorable notice, as did Vincent & Theo (1990), an evocative film about the noted artist and his brother, which was a return to form but didn’t find its audience.

The Player

Then in 1992, the maverick surprised Hollywood yet again with The Player, a black comedy about a movie executive who kills a screenwriter, his first major commercial and critical success since Nashville.

The film was enriched by cameo appearances from 66 celebrities (most memorably Bruce Willis and Julia Roberts), who all agreed to work for scale. Heralded as Altman’s comeback, The Player made Hollywood the butt of the joke. Hailed for his droll, sinuously explorative camera style, it had a showy 8 minute-opening that described vividly the ambience on a studio lot. Thematically, it was a return to Altman’s America as a place of frauds and dreamers, but the satire was not offensive and the target too easy. With a typical irony, this scathing satire of Hollywood earned Oscar nominations, including Best Director, and brought Altman back from the cold.

Altman has always struggled to get his movies made his own way. The disenchantment with the studios and their concern with marketing led to a break from the majors.

Following what he calls his “third comeback,” Altman still refuses to march in step with the conventions of traditional American cinema. “Hollywood doesn’t want to make the same pictures I do, and I’m too old to change.” But he has shown that he can sometimes get Hollywood to see things his way.

Short Cuts (1993)

Short Cuts, based on short stories by Raymond Carver, was a lengthy, complex film that interweaves the lives of two dozen characters in creating a portrait of contemporary L.A. The movie’s faithfulness to the source material was disputed, but it caught the hazy, slippery looseness of L.A., specifically the casual violence and childishness.