Research in Progress: January 16, 2025

I was a student of Robert K. Merton and Harriet Zuckerman at Columbia University, taking their vibrant classes and seminars in the sociology of science, which have influenced immensely my future thinking and my studying of the arts, theater and especialy cinema.

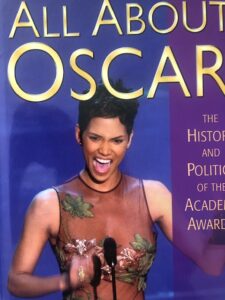

My Oscvar Book:

The Matthew Effect

As a term, the Matthew Effect was coined by the sociologist Merton, circa 1968, and then further refined in later years. Its name is derived from the Parable of the talents or minas in the biblical Gospel of Matthew.

Merton later credited his collaborator and wife, the sociologist Harriet Zuckerman, as co-author of the concept of Matthew effect.

The Matthew effect, or the Matthew principle, or Matthew effect of accumulated advantage can be observed in many fields of activity. It is sometimes summarized by the adage “the rich get richer, and the poor get poorer.”

The concept is applicable to issues of fame, reputation, achievement, and status, but it also applies to cumulative advantage of wealth, economic and cultural capital.

It has always been my wish to apply the Matthew Effect to the sociology of art in general, and the sociology of film in particular.

The concept is named according to two of the Parables of Jesus in the synoptic Gospels. It concludes both synoptic versions of the parable of the talents: For to everyone who has will more be given, and he will have abundance; but from him who has not, even what he has will be taken away.

— Matthew 25:29, RSV.

I tell you, that to everyone who has will more be given; but from him who has not, even what he has will be taken away.

— Luke 19:26, RSV.

The concept concludes two of the three synoptic versions of the parable of the lamp under a bushel:

For to him who has will more be given; and from him who has not, even what he has will be taken away

— Mark 4:25, RSV.

Take heed then how you hear; for to him who has will more be given, and from him who has not, even what he thinks that he has will be taken away.

— Luke 8:18, RSV.

The concept is presented again in Matthew outside of a parable during Christ’s explanation to his disciples of the purpose of parables. He told them, “To you it has been given to know the secrets of the kingdom of heaven, but to them it has not been given. For to him who has will more be given, and he will have abundance; but from him who has not, even what he has will be taken away.”

In the sociology of science, the “Matthew Effect” describe how eminent scientists will often get more credit than a comparatively unknown researcher, even if their work is similar.

It also means that credit is usually given–and given faster–to researchers who are already famous. Peer recognition and prizes (both symbolic and financial) are often awarded to the most senior researcher involved in a project, even if some (or most, or all) of the work was done by their students or assistants.

Stigler’s Law of Eponymy

This was later formulated by Stephen Stigler as Stigler’s Law of Eponymy: “No scientific discovery is named after its original discoverer.” Stigler named Merton as the original discoverer, making his “law” an example of itself.

Merton argued that in the scientific community the Matthew effect goes beyond the issue of reputation to one that concerns influencing wider interaction and communication systems. It plays significant role in social selection and allocation processes, often resulting in the concentration of resources and talents among a small group of scientists.

Thus, disproportionate visibility is given to articles from acknowledged authors, at the expense of equally valid or superior articles written by unknown authors.

The concentration of attention on eminent individuals can lead to the increase in self-assurance, pushing them to conduct research in important but new and risky problem areas.

In the arts, the Matthew Effect is manifest in the small group of film artists who have gained fame and status.

EGOT in the ARTS

The EGOT is the designation for the accomplishment of winning all four major American entertainment awards in a competitive category of the Emmy, Grammy, Oscar, and Tony (EGOT) awards. These awards honor outstanding achievements in television, recording, film, and theater. Winning all four awards has been referred to as winning the “grand slam” of American showbiz.

As of 2019 , only 15 individuals have achieved that record. The EGOT acronym was coined by actor Philip Michael Thomas in 1984, when his role on the new hit show Miami Vice brought him instant fame, stating a desire to complete his own EGOT-winning collection.

When coining the acronym, Thomas stated that it also means “energy, growth, opportunity and talent.” However, he also intended that the “E” should only stand for the Primetime Emmy Award, and not a Daytime Emmy. Nevertheless, two of the 15 people listed as EGOT winners have won the Daytime Emmy.

None of the 15 EGOT winners have actually earned the awards in the acronym’s order (first an Emmy, then a Grammy, then an Oscar, and finally a Tony). The closest person has been Robert Lopez, who won the “grand slam” in TEGO order.

Best Actress (Oscar Winners), by Year of Winning:

Actress whose career can be defined by cumulative advantage, namely, they have won or have been nominated for, in addition to the Oscar, awards in other mediums of entertainment, such as Tony Award in the theater, Emmy Award in television, and Grammy Awards in music.

Of the 86 Oscar wining women, only 26 (about 34 percent) have NOT won or have NOT been nominated for an award in another medium.

They are in chronological order:

Gaynor, Janet

Pickford, Mary

Shearer, Norma

Dressler, Marie

Rainer, Luise, German

Rogers, Ginger

Fontaine, Joan

Garson, Greer

Jones, Jennifer

Crawford, Joan

Wyman, Jane

Kelly, Grace

Magnani, Anna, Italian

Hayward, Susan

Signoret, Simone, French

Loren, Sophia, Italian

Christie, Julie

Fletcher, Louise

Swank, Hilary

Theron, Charlize

Cottillard, Marion, French

Bullock, Sandra

Portman, Natalie

Stone, Emma

Zellweger, Rene

Madison, Mikey

Analysis:

About 10 of the 26 women have won the Best Actress Oscar prior to the establishment of the other showbiz awards, the Tonys in 1947, the Grammys in 1959, and the Emmys.

Five of the 26 women have been foreign, French or Italian, which means that they have had no opportunity to perform in the U.S. and compete for awards.

Significantly, 51 of the 86 female winners have been nominated for or have won at least one of the three showbusiness awards: Tony, Emmy, and Grammy.

Updated: January 16, 2025