One of the most haunting films about children and the educational system ever made, Jean Vigo’s Zero for Conduct (Zero de Conduite) depicts as well as celebrates anarchic rebellion.

Produced, written and directed by Vigo, this feature is loosely based on his personal painful experience in a boarding school.

Grade: A (***** out of *****)

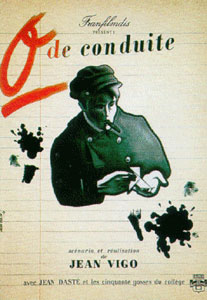

| Zéro de Conduite | |

|---|---|

Film poster

|

|

The tale describes the (mis)adventures of a group of young pupils as they endure the absurdities and deprivations that are forced upon them by their rigid authoritarian teachers.

Except for Huguet, a normal guy with the kids, all the other teachers are repressive and/or creepy–in one way or another. Delphin, for example, who’s pompous and platitudinous principal, is a bearded dwarf.

There’s punishment for the slightest violation of the rules, which results in a zero for conduct, meaning detention on Sunday

In the first scene, two boys, Caussat and Bruel, amuse themselves on the train while heading back to their provincial school.

The principal disapproves of the close friendship between Bruel and Tabard, the new boy in class, who’s shy and lonely.

For his part, Tabard curses his fat and repulsive chemistry teacher, who fondles him. Though forced to apologize publicly in front of the principal and mates, Tabard does the opposite, bursts outing,” I say shit on you!”

Soon, seemingly minor tensions escalate, devolving into an open rebellion by the students. The kids protest the unvarying beans served them in the dining hall.

The revolt begins in the dormitory with Tabard reading a proclamation that denounces the administration and exhorts open rebellion. In a state of frenzy, in what is the film’s most visually striking piece, the boys overturn beds, and enormous pillow fight ensues. This is shown through stunning, dream-like montage of a parade involving the jubilant boys.

The following day, the priest and other officials are invited to the Commemoration Day ceremonies. Figures of authority are juxtaposed with rows of large dummies.

The four courageous kid leaders, who were hiding out in the attic, are now starting to pelt the guests with old books, pots, and stones. Huguet urges them on and encourages other pupils to join in.

As a result, the officials take refuge as the four victorious revolutionaries climb up on the roof to declare their freedom and independence.

Shown in a private screening, on April 7, 1933, to an invited audience, the movie immediately aroused a huge controversy. As a result, Zero for Conduct was banned by the Board of Censors. The government feared that the film might create disturbances and hinder the maintenance of order in other places.

The movie didn’t disappear entirely, though. It circulated in a limited way through various French cinema clubs in and out of Paris. Nonetheless, only after the Liberation of WWII, Zero for Conduct was allowed wider theatrical distribution, after a 12-year-ban.

At once an attack on the archaic and rigid French educational system and a sharp psychological study of youth behavior, Zero for Conduct also represents a poetic evocation of childhood. The predominant mode of French social realism is undermined in the name of a style that is more defined by poetic imagery.

Ideologically, the film’s message is clear: Forces of authority in the adult world all conspire to inhibit children’s natural instincts and suppress their wild spirits.

As depicted by Vigo, the guardians of morality are not necessarily realistic figures as much as they are a reflection of the children’s subjective POV. Vigo was aiming to accord children the respect and awe that that he though they deserved as human beings, but were denied of.

The adults in the film are intentionally mere puppets. This is especially clear in the case of the principal, who comes across as a man with an inflated ego and dwarf-like body, with a shrill voice, and ridiculous beard to match.

The school in the film is a microcosm of the larger societal system, in which a minority uses and abuses its power to force its will on a majority that’s either weak or indifferent.

That said, the movie, nonetheless suggests the potential power of the weak and submissive to unite and organize themselves in the effort to overthrow their oppressors.

The rebellion and victory at the end of the movie, seems to echo the sentiments of the French revolutionary movement. Indeed, Tabards insolent retort, “I say, shit on you!” bears wider, more relevant political significance, which goes way beyond the educational environment.

A personal film, “Zero for Conduct” reflects Vigos memories of unhappy childhood. In the film, the sensitive Tabard represents the alter ego of the young Vigo; the director was also influenced by the imprisonment of a colleague of his father. Vigo succeeds in conveying the childrens subconscious minds. The dormitory revolution scene moves from a realistic to lyrical, even surreal level. Vigo uses slow motion, while playing Maurice Jauberts spooky music in the background.

The film is not flawless. Due to production conditions, the sound quality is not very good. There are several loose ends, a result of the fact that there was never a finished script, though some of the lack of continuity is by design. Though unintended by Vigo, the jumpy narrative later influenced the New Wave directors. The cast is largely made of nonprofessionals, which may account for the uneven acting.

Shooting much more footage than he needed, Vigo chose the most genuine sequences, without bothering about missing connections. The dialogue may be sparse and simple, but the visual images are sharp and strong.

Indeed, several scenes stand out in their elaborate mise-en-scene, which fuses editing and lighting. A lot has been written about the “rain of feathers” sequence, and the scene in which the three boys, having been ordered to stand still for two hours at the bedside of a supervisor, plead to allow one of them, who had developed a stomach ache, to go to the bathroom. Their repeated pleas become sort of an incantation that takes on a hauntingly surreal quality.

Scholars have singled out the films dense text, rich with cinematic references: Jean Daste does a turn as Chaplin; the pillow fight scene recalls a similar one in Abel Gances “Napoleon”; and the brief animated cartoon in a study hall brings to mind Emil Cohl. Once released, the movie proved to be influential: Francois Truffaut’s seminal feature debut “The 400 Blows,” and Lindsay Andersons If, the story of a rebellion in a boys school in England, owe a lot to Vigo.

In 1946, the MOMA screened Zero for Conduct for the first time, after which the movie began a commercial run in New York City. A brief scene of adolescent nudity that was deleted by the state censors was restored in 1962. Unfortunately, no complete version of the film has survived.

Made on a low budget (200,000 francs), “Zero for Conduct” was shot by Vigo’s friend Boris Kaufman, the younger brother of the Soviet “Kino-Eye” pioneer Dziga Vertov.

Credits

French title: Zero de Conduite

Running time: 44 minutes; also 41 minutes

Produced, written, directed, edited by Jean Vigo.

Cinematography: Boris Kaufman

Music: Maurice Jaubert

About Jean Vigo

Vigo’s brilliant career was cut short by his death from septicemia at the young age of 29. Nonetheless, despite this tragedy, in the few pictures that he was able to complete, Vigo showed complete mastery of the film medium as both a visual force and socio-ideological tool.