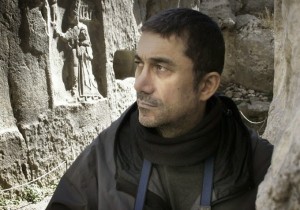

The films of Turkish auteur Nuri Bilge Ceylan, whose name is still little known in America (and outside the festival circuit), are intimate epics in every sense of the term: ambition, scope, depth—and running time.

The films of Turkish auteur Nuri Bilge Ceylan, whose name is still little known in America (and outside the festival circuit), are intimate epics in every sense of the term: ambition, scope, depth—and running time.

At three hours and sixteen minutes, his latest, “Winter Sleep,” was the longest feature in competition at the 2014 Cannes Film Fest. The sprawling, multi-layered film must have impressed the jury and its president (Aussie Jane Campion) as it won the top prize, the Palme dÓr. (Ceylan is the recipient of various awards at Cannes, but he has never won the big prize).

Like Ceylan’s last film, “Once Upon a Time in Anatolia,” the tale is set in Turkey’s rural region, rough place to live, made even tougher in the winter due to snow, ice and wind.

Like Ceylan’s last film, “Once Upon a Time in Anatolia,” the tale is set in Turkey’s rural region, rough place to live, made even tougher in the winter due to snow, ice and wind.

The script, co-penned by the director and his wife Ebru Ceylan (a talented actress and writer), is very loosely based on several short stories, “Excellent People” and “The Wife,” by the Russian master Chekhov. But, as always, Ceylan shapes the literary source to his own specifications, defined by ambitious existential and emotional goals.

Some American critics (not me) found the film too slow, static, and verbose, but I was consistently intrigued by the poignant dialogue, sharp characterization, sublime actingof the entire ensemble, and visual imagery, which is often majestic.

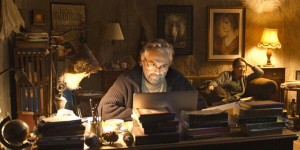

The tale depicts several days in the life of a stalky middle-aged man named Aydin (Haluk Bilginer), a hotel owner and landlord in a remote Anatolian community, in which the houses seem to be carved into hard rocks that look majestic in their size, sharp forms and color configuration of white, gray, and yellow.

The narrative unfolds as a detailed anatomy of a troubled triangle, centering on Aydin’s relationships with his very young and beautiful wife, Nihal (Melisa Sözen), and his sister Necla (Demet Akbag), a recent, bitter divorcee. Structurally, the film unfolds in four chapters or movements, each based on a major encounter (and confrontation) between Aydin and his poor tenants, Necla, Aydin and Nihal (the longest and most interesting section), and in the end between Aydin and a school teacher (see below). There are also interludes in which Aydin interacts with his young Japanese guests, chatting in broken English about the merits of wasabi.

Going through a winter of discontent, he is restless and unsatisfied with most of his interactions, which he dominates with his charisma, wit, and overbearing personality. This includes his necessary daily communication with Hidayet (Ayberk Pekcan), his right-hand man, a manager who looks after his tenants, drives him around in his orange jeep, which provides the only vivid color, especially when contrasted against the majestic vistas covered with white now.

Going through a winter of discontent, he is restless and unsatisfied with most of his interactions, which he dominates with his charisma, wit, and overbearing personality. This includes his necessary daily communication with Hidayet (Ayberk Pekcan), his right-hand man, a manager who looks after his tenants, drives him around in his orange jeep, which provides the only vivid color, especially when contrasted against the majestic vistas covered with white now.

As the story progresses, more characters are introduced, with the same ease and precision as the main triangle. We meet the opinionated teacher Levent (Nadir Saribacak), the scheming Imam Hamdi (Serhat Kilic), and the latter’s proud, hot-blooded brother, Ismail (Nejat Isler).

A reluctant landowner, Aydin has inherited from his father not only the land but also the authority and power that come along with the wealth, which causes resentment and contempt among the inhabitants.

The text’s sexual and class politics are demonstrated in some poignant scenes, which benefit from Ceylan’s masterful mise-en-scene and rigorous framing. In one of the strongest acts, the boy who had earlier thrown a stone at Aydin’s car is brought by his uncle to ask for forgiveness. The boy is the angry son of a poor alcoholic tenant, threatened with eviction. Expected to kiss Aydin’s hand, the rebellious and reluctant boy gets up and approaches Aydin, who extends his hand, waiting for the ritualistic gesture. But instead, the boy stares long and steady at his oppressor until he faints, falling to the ground.

Most of the film is set indoors, with Aydin sitting at his desk writing (or trying to write) while engaged in lengthy conversations with his wife or sister. The two women are vastly different but they share one thing in common, an ambivalent attitude toward Aydin that is equal parts admiration and disdain. This is a result of their socio-economic status, as both are dependent on him even if had robbed them of their autonomous identity and individual desires.

Most of the film is set indoors, with Aydin sitting at his desk writing (or trying to write) while engaged in lengthy conversations with his wife or sister. The two women are vastly different but they share one thing in common, an ambivalent attitude toward Aydin that is equal parts admiration and disdain. This is a result of their socio-economic status, as both are dependent on him even if had robbed them of their autonomous identity and individual desires.

As for Nihal, who age-wise could be Aydin’s daughter, she too has lost her love and respect for her cynical and overbearing husband, who patronizes everything that she does, including her charity work, raising funds for local schools. In their biggest argument, he calls her a “chronic philanthropist” a “lazy parasite,” demanding to see the records of donations and resentful of her warm affection for the local school teacher.

Like other Ceylan’s films, “Winter Sleep” owes a literary debt to the Russian playwright Chekhov, whose influence is formally acknowledged at the end. We witness the various family conflicts, the yearning to live in a big, more interesting and vibrant place, the need to experience high culture (there are literary quotes of and references to Shakespeare and other writers), the desire to be loved and be fulfilled.

“Winter Sleep” may be the most demanding and challenging film–but (for me) not the best–in Ceylan’s growing output. This ultra-detailed psychological study places its protagonist under the camera’s microscopic gaze, depicting a soul-seraching journey of a man who has been alienated from himself and others, and has come to reconize (perhaps too late) that his very existence is out of time and out of place.

Most of Ceylan’s film work is male-dominated, offering meticulously constructed portraits of ordinary lives, defined by the disparity of hopeful (yet unrealized) ideals and mundane reality. However, unlike previous films, such as the 2008 noir melodrama, “Three Monkeys,” “Winter Sleep” is an intimate, domestic, mostly interior drama, whose emotional power is a result of many accumulated details and sharp observations.

“Winter Sleep” is the kind of art film seldom seen in the U.S.–it seems to have been conceived and executed made without any considerations for commerce or concessions to the trendy marketplace.

It’s about time that Ceylan, whose films have been seen by few viewers, gets a complete retrospective in the U.S.