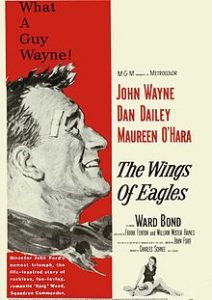

Reviewing John Ford’s biopic, The Wings of Eagle, a sentimental, sugarcoated salute to Frank (Spig) Weed, the noted naval warrior, the acclaimed critic Arthur Knight wrote in the Saturday Review: “Not until this picture, however, could Hollywood be accused of cannibalizing, of making film capital out of film people.”

While the movie was in production, Ford called it the tender-tough account of the extraordinary life of Commander who was a pioneer Navy Flier and a Broadway playwright and successful Hollywood scriptwriter–above all it’s the story of a very brave man.”

But the curious thing about this picture is that even though its makers were on intimate terms with their subject, Frank (Spig) Wead, it comes out as more fiction than fact.

“Wings of Eagles” was perceived as an uncritical memorial to the noted flier-writer, who succeeds against all medical advice to overcome his paralysis.

The yarn begins in 1919, when the aviation branch of the U.S. Navy consists of only 19 airplanes and 30 men. In an effort to dramatize its interest in aviation and win the public support for Congress appropriations, the Navy stages some international seaplane races. In 1923, the famous Schneider Cup is won by Frank (Spig) Wead (John Wayne), the Annapolis graduate, and his team.

In quick succession, Wead and his peer Lt. John Price (Ken Curtis) break the seaplane endurance record, set a new seaplane distance record, and break the seaplane speed record.

Wead’s passionate commitment to all things of Naval aviation takes a toll, leading to strains with his wife Minnie (Maureen O’Hara), who feels neglected. Minnie resents the demands made on her husband, and unable to cope with his frequent transfers in line with his duty, she hopes he will be thrown out of the Navy. But it doesn’t happen and the couple separate. In fact, Wayne becomes so estranged from his two daughters that when he comes to visit them they don’t recognize him.

Ironically, on the night that Wead receives word of his appointment as a skipper of a fighting squadron, he breaks his neck in a fall down the stairs at his own home. As a result, the doctors declare him a hopeless paraplegic. He persuades Minnie to leave him and cultivate her own life with their children.

Meanwhile, he’s nursed back to health by his old Navy mechanic, Sergeant Carson (Dan Dailey), and begins a new career as an author, playwright and screenwriter, with many of his works dealing with themes and issues of aviation. Wead wrote Dive Bomber, Hell Divers, Test Pilot, Ceiling Zero, and They Were Expendable, his last notable hit in 1945, before dying in November 1947.

Later on, reconciliation is arranged between Wead and Minnie, who’s now a successful business woman, but it’s short-lived as she refuses to submerge herself into his career. The motives for her behavior are not very clearly described, though there are suggestions that she might have taken to drink and herself neglected their children. Of all their mutual films, in this one their relationship is the weakest because O’Hara’s role is much less developed than Wayne’s–the focus of the narrative.

Wead then heads to the Pacific to put into effect his revolutionary idea for jeep carriers, as a follow-up of the big carriers and replacement of the lost planes. However, after the battle in Kwajalein, he collapses, though is still able to see the results of his work, when he is hoisted via breeches buoy to a destroyer for the last trip home. At long last, Wead’s long fight to establish a strong air arm for the Navy is fulfilled.

Wead adored the Navy and was a devoted patriot with uncomplicated loyalty and as such offered a perfect subject for John Ford, who also emphasizes Spig’s elemental manhood. Many critics noted that, more than any John Ford film since “The Quite Man,” in 1952, this film has “the air of a completely personal statement, and the person it reveals is somewhat less than admirable.”

The Hollywood Reporter critic wrote that the film “lacks a summation worthy of its parts although its parts are as good and often superb.” While John Ford was criticized–“it does seem that his addiction to the folksy laugh, the quick tear, and to a cheap and sentimental chauvinism has begun to trip him up–John Wayne received mostly favorable reviews.

It was a good vehicle for Wayne, whose screen image was as a rugged, impulsive, and daring hero was congruent with that of Spig’s.

Ruth Waterbury wrote in the “Los Angeles Examiner” (February 21, 1957) that the picture “does a wonderful thing for John Wayne, it lets him get under the skin of a real part and prove that he is very much more than the ‘action’ star.” She then elaborated: “The transition of a man, full of laughter and vitality, into a helpless cripple, is poignant and terrible and Wayne conveys this poignancy.”

Ford’s son Dan later observed: “the movie is revealing because it is the story of a belligerent, brave, eccentric visionary, a man of fanatic dedication who, like Ethan Edwards in The Searchers, is doomed to be alone. More than the story of Spig Wead, it is the story of John Ford, the story of a career man.”

Credits

Produced by Charles Schnee.

Associate Producer: James E. Newcombe.

Directed by John Ford.

Assistant director: Wingate Smith.

Screenplay: Frank Fenton and William Wister Haines, based on the life and writings of Commander Frank W. (Spig) Wead.

Camera: Paul C. Vogel.

Editor: Gene Ruggiero.

Art direction: William A. Horning and Malcolm Brown

F/X: Arnold Gillespie and Warren Newcombe

Music Score: Jeff Alexander