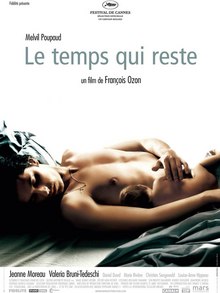

Time to Leave is the first explicitly gay feature from Francois Ozon, better known as France’s woman director, having previously made “Under the Sand,” “Swimming Pool” (both star vehicles for the idiosyncratic Charlotte Rampling), and, of course, 8 Women, which was like the who’s who in French cinema, including Catherine Deneuve and Isabelle Huppert.

| Time to Leave | |

|---|---|

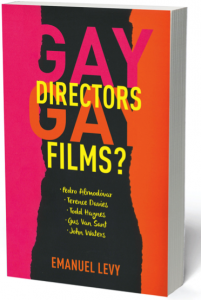

Poster for the film

|

|

“Time to Leave” offers no rousing speeches about living life to the fullest or heartfelt soliloquies on the nature of existence, only the bitter admission that death happens to everyone and there is no use in trying to stop it. Yet through its emotional honesty, Time to Leave offers many candid and moving moments. There are tears, but because they arrive after long dry spells, they feel earned.

We would like to think that we will end our lives at an older age and on a high note, but for Ozon’s protag Romain (Melvil Poupaud), the news of death hits at a time of bitter discontent. In an intoxicating performance, Poupaud ignites what is otherwise an understated film with potent mixture of anger and desperation.

When told he has terminal cancer, Romain refuses chemotherapy–what’s the point–and prepares to tell his family the news moments before he meets them for dinner. Once inside, however, he realizes he despises them too much to offer his love or accept their condolences, preferring to keep his secret smoldering inside of him.

When his sister speculates why Romain, a professional photographer, does not take pictures of her children, he tells her because your ugly mug would be in the picture. Poupauds controlled delivery lends these words a chilling sincerity, as if he was dredging them up from the darkest places in his soul. His family tries to reach him in the best way they know how, perhaps because they realize that he is incapable of hating anyone as much as hating himself.

Or rather, he hates what he has become. Flashbacks of Romain as a child, growing increasingly vivid as his death approaches, reveal a self-idolization that borders on the extreme. However, these flashbacks also reveal a more universal idea, that the past holds moments of beauty and mystery we are incapable of replicating in the present. It is through this impossible longing that Romain establishes himself as a man worthy of screen treatment and our empathy, even though his behavior can be–and occasionally is– monstrously selfish.

Romains worst moments are actually the movies best. Ozon and Poupaud strip down human nature to its core components, bringing us closer to ugly truths than most movies, particularly American ones dealing with death.

Once Romains behavior begins to take a turn towards the better, Time to Leave loses considerable force. It is not that the last third of the movie is bad. Ozon is too unconventional a writer to resort to cheap sentimentality, and Romains character arc does not stretch credulity too muchhe is no Mr. Nice Guy.

However, Romains road to redemption and tranquility lacks the tension and spontaneity of the movies first half, where each confrontation took the story to unforeseen places. Take, for example, the wonderful, the film’s only lyrical scenes, between Romain and his loving and eccentric grandmother, played by Jeanne Moreau is a husky voice that’s sheer music to our ears. However, once Romain stops battling his demons, Ozon settles into complaisance as well, as if he has nothing left to prove.

Throughout, though, Ozon keeps the frames full and alive, offering visual pleasures that more plot-driven movies often overlook. Those who hesitate to see a slow-paced, minimalist film (basically one-character drama) need not fear–at 82 minutes, Time to Leave does not overstay its welcome, and the ending, with Romain at the beach alone, is extremely satisfying.

If nothing else, it’s worth seeing the movie for Poupaud, who brings passion and dimension to every scene. He does not coast through his scenes on learned mannerisms but places himself in every situation, engaging our attention as he probes for the appropriate words and reactions. This is particularly clear in the film’s early chapters, which describe Romain’s breakup from his lover (after one particularly steamy sex scene).

A lesser actor would handle Romains transformation with straightforward conviction, but Poupaud leaves room for ambiguity and diverse interpretation by maintaining a tension between his words and his actions. As intimate as Poupaud’s performance is, there will always be something unknowable about his character, which makes him all the more compelling to watch. An air of mystery is appropriate for a movie about untimely death, especially one as challenging as this one.

Credits:

Directed, written by François Ozon

Produced by Oliver Delbosc and Marc Missonnier

Written by François Ozon

Music by Valentyn Sylvestrov

Cinematography Jeanne Lapoirie

Edited by Monica Coleman

Distributed by Mars Distribution

Release date: May 16, 2005 (Cannes); November 30, 2005 (France)

Running time: 81 minutes

Budget $4.4 million

Box office $2.9 million

Written by Kate Findley