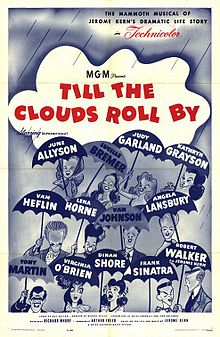

Upon their return from their New York honeymoon, Vincente Minnelli and Judy Garland set out to work on what will be the first professional collaboration during their marriage. Freed was preparing a musical biography of Jerome Kern, entitled “Till the Clouds Roll By,” with an all-star cast. Judy, the studio’s top singing star, was cast as Broadway’s musical comedy luminary, Marilyn Miller.

Grade: C+ (** out of *****)

My biography of Minnelli, the first one about him.

Less than a month after production began, in October 1945, Kern died suddenly, which forced a major rewrite of the script. In the six months that it took to shoot the production, Freed lined up one director after another. Busby Berkeley, not the best choice to begin with, lasted only a few weeks.

Henry Koster replaced Berkeley, but he contributed little to the film since he was replaced too. Richard Whorf was brought in, and he’s the one who received the dubious directorial credit. The film’s song-medley finale, with Sinatra in white tails crooning “Ol’ Man River,” was directed (uncredited) by George Sidney. Choreographer Robert Alton was the only one to stay on board throughout.

Minnelli staged Judy’s sequences, and was acknowledged in the opening credits. The Till Clouds material was the first to be shot, in October 1945, due to Judy’s pregnancy. Minnelli had to come up with a clever staging of the songs to hide Judy’s pregnancy bump.

By necessity, the film lacked unified vision. Minnelli’s sequences aside, this musical is a product of moviemaking-by-committee.

| Till The Clouds Roll By | |

|---|---|

theatrical release poster

|

|

Till the Clouds was the first and blandest of MGM biopics about Broadway’s composers, a cycle that included tributes to Rodgers and Hart (Words and Music, 1948), Kalmar and Ruby (Three Little Words, 1950), and Sigmund Romberg (Deep in My Heart, 1954).

The story centers on Kern’s courtship of his future wife, Eva Kern (novice actress Dorothy Patrick. It also deals with Kern’s lifelong friendship with song arranger, James Hessler, and the latter’s rebellious child. But, inexplicably, the movie never mentions Kern’s own daughter. At least seven writers worked on script, which was constricted by Freed’s reverence for Kern. Kern was played by Robert Walker with a solemn dignity. As his pal, Hessler, Van Heflin was mediocre, and Lucille Bremer, as Hessler’s irritable daughter, was miscast.

Unfortunately, there was too much story and too few musical specialties, which were listless. The films popular singers, Lena Horne, Dinah Shore, Kathryn Grayson, Tony Martin, could project little personality. Only a few numbers show some vivtality, such as Angela Lansbury’s music-hall turn.

The freshness of the three Minnelli sequences, which appear in the middle of the picture, only underlines the surrounding dullness. Judys Marilyn Miller is first seen at the opening-night intermission of her 1920 triumph, Sally. The setting is essential Minnelli: the anteroom to the star’s dressing room is a cherry-red chamber with white Grecian busts, crowned by top hats of Miller’s admirers. Judy acknowledges the praise of her fans, and plans the next change with her dresser, while humming a new arrangement with the conductor.

In one extraordinary take, Minnelli follows Judy as she strides through the wings past the multicolored spotlights onstage toward the unlit set, a restaurant sink with dirty dishes. After checking the placement of her props with the stage manager, Judy gets the spotlight. In a quiet but plaintively emotional voice, she sings Millers original song, “Look for the Silver Lining.” The lyrics’ wistfulness are underscored by her concentration on the mundane tasks, keeping her hair out of her face and her sleeves out of the sinks suds. Due to Minnellis shaping, there’s dual message at work.

Up to now, every song had been staged as a tableau seen from the audience’s perspective, concluding with shots of their applause. But here, the public’s presence is indicated only by the play of lights on Judy’s face as the curtains close and she basks in applause. Shot from the performer’s P.O.V., the sequence is about the magic of live musical comedy, the combination of professionalism under pressure and talent, which made both Marilyn Miller and Judy the stars that they were. In the process, Judy, in a rare happy phase, becomes a legend in the making. Unlike the other stiff performers, Judy comes across as both flesh and blood and larger than life.

From the intimacy of Sally, Minnelli moves into the spectacular with numbers from the Kern-Miller’s musical, Sunny. The show’s circus setting is far more dazzling than Busby Berkeley. The sequence opens with a vertiginous flourish–from atop the offstage rafters. Minnelli focuses on a stagehand riding a spotlight flashing red, then the camera plummets as the set comes ablaze with light. The set, a center ring of baroque fantasy done in scarlet and white, reflects Minnelli’s tent-show childhood dreams. There’s marching band in red; gold-sprayed elephants surrounded by attendants in pastel Indian silks; tightrope walkers in silhouette against the big canvas. At the center, Judy, in white tutu, double leaps in one bound onto her pony’s back for a speedy canter around the gold-sawdust ring.

Minnelli’s gift for blending an infinite number of seemingly random details is a marvel of visual harmony, keyed with precision to music. As a tribute to the magic of circus, Minnelli revels in the screen’s possibilities for spectacle, climaxing with a dizzying final image. The camera is at bird’s eye-level, capturing a spinning female aerialist suddenly catapults herself aloft in great arcs over the earthbound antics below. From the title song, Minnelli dissolves to a subdued palette for “Who” showcasing Judy as Miller the sophisticate.

Oscar Hammerstein’s lyrics proved jovial, as the expectant Judy crooned, “Whoooo stole my heart away to ardent chorus boys doffing their top hats one by one. Though not as elaborately staged, “Who” prefigures Minnelli’s “I’ll Build a Stairway to Paradise” in American in Paris. Flanked by the men, Judy glides airily down a white staircase to deliver a carefree solo. Alton’s choreography is accentuated by the monochromatic chic of Minnelli’s concept. The chorus is in black-and-white, and Judy in yellow chiffon is the only spot of color. “Who” flaunts the ever-shifting mobility of Minnelli’s camera. Most of Alton’s numbers are stagey, but, in this one, Minnelli recaptures the glory of a bygone theatrical era in uniquely fluent screen terms.

The always-pragmatic Freed needed to figure out how the pregnant Judy could be used in the Kern picture. Pre-production for Till the Clouds was accelerated so that Judy could complete her work before her pregnancy showed. Minnelli handled Judy’s three songs and her dramatic scenes with Robert Walker and Lucille Bremer, who played Kern and his niece, respectively.

This formulaic biopicture was planned as yet another all-star extravaganza. How could these pictures be entertaining and realistic, Minnelli wondered, when much of the composer’s work was static, not to mention the avoidance of any controversial personal material. It was simply not cinematic enough to show a composer sitting at a piano or relating the chronology of his songs. This is the reason why Minnelli never made a musical biopicture despite their popularity at the time.

Judy was four-months-pregnant when shooting began in October 1945. Her songs didn’t take long to shoot, and Minnelli was able to do his work in two weeks. Minnelli was the proudest of staging “Sunny,” a number that conveys the essence of circus life. It had to look as if the number was being done on stage, and a boom camera swept in to cover the action. Judy sang the song and ran behind a group of extras, while her double jumped on a horse and galloped.

For Judy’s second song, “Look for the Silver Lining,” Minnelli chose to show her washing dishes, just as Marilyn Miller did when she had introduced the song on stage. Judy felt that her pregnancy showed in the last number, a glamorous mounting with a huge chorus and spiral stairway. Judy felt ridiculous, running up to each man in the scene and singing the question, “Who.”

With her numbers completed, Judy retired to await their baby’s birth. For her, those months were the longest of being professionally inactive since she had arrived at Metro. By 1945, she had made 23 films, and the demands on her energy and health were excessive. Minnelli had to report daily at the studio, so it became Judy’s responsibility to supervise the expansions of their house: the building of a nursery, an enlarged kitchen, and another dressing room.

Credits:

Directed by: Richard Whorf, Busby Berkeley, Henry Koster, Vincente Minnelli

(Judy Garland sequences.), George Sidney (“Ol’ Man River”/Finale)

Produced by Arthur Freed

Screenplay by Myles Connolly, Jean Holloway, George Wells

Uncredited: Fred Finklehoffe, John Lee Mahin, Lemuel Ayers, Hans Willheim

Story by Guy Bolton

Music by Music: Jerome Kern

Lyrics:

Leonard Joy

Otto Harbach

Ira Gershwin

P. G. Wodehouse

Guy Bolton

Jimmy McHugh

Edward Laska

Oscar Hammerstein II

Jerome Kern

Herbert Reynolds

Dorothy Fields

B. G. DeSylva

Cinematography George J. Folsey, Harry Stradling

Edited by Albert Akst

Production company: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

Distributed by Loew’s, Inc.

Release date: December 5, 1946 (New York); January 16, 1947 (US)

Running time: 132 minutes

Budget $3,316,000

Box office $6,724,000