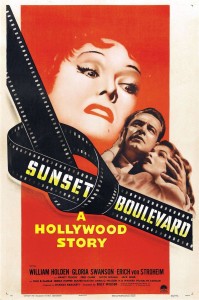

Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard is one of his three or four masterpieces, a seminal Hollywood black comedy-satire, which unlike most films keeps improving with the passage of time.

Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard is one of his three or four masterpieces, a seminal Hollywood black comedy-satire, which unlike most films keeps improving with the passage of time.

Benfiting from a glorious and iconic cast, the film concerns a faded silent film star, played by Gloria Swanson (in a variation of her own onscreen persona), who lives in the past with her butler (and former husband), while sheltering a young hack screenwriter as a kept lover.

Produced by Charles Brackett and co-written by Billy Wilder and Brackett, “Sunset Boulevard” was nominated for several Oscar Awards, but the big winner in 1950 was Joseph Mankiewicz’s “All About Eve,” which also offers a biting look at showbusiness, this time the Broadway theater.

With this film, Wilder mixes a psychological melodrama with a dark comedy for the first time. Indeed, at once bitter and satirucal, the film provides a fascinating look at the Hollywood film industry at a crucial time of its history.

“Sunset Boulevard” symbolizes in its style the transition from the already decaying old glamour of the movie capital to a more cynical and world-wise “New Hollywood.”

The idea is clear from the opening sequence, which reverses the convention of “meet cute” of most romantic comedies and dramas. In the first scene, we view the body of Joe Gillis (William Holden) floating face downward in a swimming pool, as the dead man’s voice directly addresses us (“Poor devil–he always wanted a pool!”), as though viewing himself from a distance.

Joe then takes us back to the beginning of the strange series of events that led to his own demise. A down-and-out Hollywood hack writer, Joe left his comfortable spot on a Dayton newspaper in the naive belief he’d make it “big” in California. Now, he has to fast-talk the men from the collection agency (Larry Blake and Charles Dayton) in order to keep his car, and beg his contact (Fred Clark) at Paramount to get him a third-rate job as script doctor. While there, he meets an idealistic young would-be writer, Betty Schaefer (Nancy Olson), who believes in his talent and likes him, but before their relationship can even develop he finds himself pursued by bill collectors and makes his getaway by hiding on the grounds of a seemingly abandoned mansion.

Joe then takes us back to the beginning of the strange series of events that led to his own demise. A down-and-out Hollywood hack writer, Joe left his comfortable spot on a Dayton newspaper in the naive belief he’d make it “big” in California. Now, he has to fast-talk the men from the collection agency (Larry Blake and Charles Dayton) in order to keep his car, and beg his contact (Fred Clark) at Paramount to get him a third-rate job as script doctor. While there, he meets an idealistic young would-be writer, Betty Schaefer (Nancy Olson), who believes in his talent and likes him, but before their relationship can even develop he finds himself pursued by bill collectors and makes his getaway by hiding on the grounds of a seemingly abandoned mansion.

A voice from within the house calls to him, and Joe finds Norma Desmond, a garish, middle-aged woman (perfectly cast with Gloria Swanson), readying a funeral for a recently deceased chimpanzee. “I know you,” he exclaims. “You’re Norma Desmond. You used to be big!” “I still am big,” she insists. “It’s the pictures that got small!”

Out of desperation, Joe accepts Norma’s offer to help prepare a “comeback script” which would have Norma playing the youthful Salome. The money is good, but Norma insists that Joe move into her house, thus gradually becoming one of her possessions. Filled with mementos of her career, the house is Norma Desmond, still statuesque and impressive from a distance but on closer look, it’s cracked, faded, and wrinkled.

The swimming pool where Clara Bow once relaxed is filled with rats (though Norma has it repaired for Joe). Guarding both the mansion and the faded star is Max Von Mayerling (Erich von Stroheim), once Norma’s director and husband, now a waiter-valet-chauffeur dressed up in a monkey suit.

Former movie greats Buster Keaton, H. B. Warner, and Anna Q. Nillson appear as what Joe snidely refers to as “the waxworks,” Hollywood has-beens, who visit on bridge night. Yet the focus remains on Norma’s decadently and deadly fascinating love-hate relationship with the wisecracking writer.

Former movie greats Buster Keaton, H. B. Warner, and Anna Q. Nillson appear as what Joe snidely refers to as “the waxworks,” Hollywood has-beens, who visit on bridge night. Yet the focus remains on Norma’s decadently and deadly fascinating love-hate relationship with the wisecracking writer.

In the film’s central scene, Max shows old Desmond movies as Norma and Joe sit on the couch and watch. “We didn’t need dialogue in those days,” she sighs wistfully. ‘We had faces then!” At an elaborate New Year’s Eve party that Norma throws just for the two of them, Joe tries to break off the relationship by trying to move in with his old buddy, bohemian writer Artie Green (Jack Webb), the screen’s first suggestion of the fifties beatnik. But Norma’s attempted suicide brings him back.

Finally, Max gets out the old limousine and escort Norma to the Paramount lot, where she visits with old friend Cecil B. De Mille, trying to persuade the embarrassed director to do her next picture. Shortly thereafter, she learns that Joe is secretly meeting Betty in the deserted studio at night to work on a screenplay and that the girl, though engaged to Artie, has fallen in love with Joe.

Betty’s freshness and talent represent Joe’s future redemption as a writer and as a man. When he tries to walk out on Norma, she fires the fatal shots and the picture comes full cycle. Norma finally gets her wish. As she is escorted out of the house by the police, the news cameras are rolling, she makes her exit as a grotesque caricature of an old star.

Gloria Swanson played Norma with such conviction that people refused to believe it could be anything but autobiographical picture. Holden, formerly a rather bland leading man, emerged as a new kind of star, and would win an Oscar for another Wilder’s black satire, “Stalag 17.”

Gloria Swanson played Norma with such conviction that people refused to believe it could be anything but autobiographical picture. Holden, formerly a rather bland leading man, emerged as a new kind of star, and would win an Oscar for another Wilder’s black satire, “Stalag 17.”

Billy Wilder and Charles Bracket experimented with innovative styles in dialogue and camera work, but it’s love-death angle of Norma and Joe that people remember the most, reflecting the self-destructive mood of Hollywood as it entered a new, uncertain decade.

Acerbic, Fact-Inspired Scenario

Norma Desmond’s eccentric and disturbed persona mirrors aspects of several faded silent film stars, such as the reclusive Mary Pickford and the mentally disturbed Clara Bow. It is a fictional composite inspired by several women, not a thinly disguised portrait of one particular star. Even so, some critics see close resemblance to such stars as Norma Talmadge, beginning with the first name and the film’s grotesque and predatory silent movie queen. The character’s name may be a combination of the names of silent actress Mabel Normand and director William Desmond Taylor, a friend of Normand’s who was killed in 1922 in a much publicized but never resolved mystery.

Wilder and Brackett worked on the script in 1948, but the result did not satisfy them. D.M. Marshman Jr. a former Life magazine writer, was hired to help develop the storyline after Wilder and Brackett were impressed by his critique of their 1948 The Emperor Waltz (one of Wilder’s weaker films).

Wilder and Brackett worked on the script in 1948, but the result did not satisfy them. D.M. Marshman Jr. a former Life magazine writer, was hired to help develop the storyline after Wilder and Brackett were impressed by his critique of their 1948 The Emperor Waltz (one of Wilder’s weaker films).

In order to keep the story’s details from the top execs of Paramount and avoid the stricture of censorship, they submitted a script of few pages. The Breen Office insisted certain lines be rewritten, such as Gillis’s “I’m up that creek, and I need a job,” which became “I’m over a barrel, and I need a job.”

Paramount thought that Wilder was writing a story called A Can of Beans (which did not exist) and granted him freedom. Only the first third of the script was done when shooting began, and Wilder was unsure of its ending.

The script contains darkly humorous, bitingly cynical references to Hollywood. Joe Gillis sums up his writing career as: “The last one I wrote was about Okies in the dust bowl. You’d never know, because when it reached the screen, the whole thing played on a torpedo boat.” Later on, when Betty says, “I’d always heard that you had some talent,” he quickly replies, “That was last year. This year I’m trying to make a living.”

The script contains darkly humorous, bitingly cynical references to Hollywood. Joe Gillis sums up his writing career as: “The last one I wrote was about Okies in the dust bowl. You’d never know, because when it reached the screen, the whole thing played on a torpedo boat.” Later on, when Betty says, “I’d always heard that you had some talent,” he quickly replies, “That was last year. This year I’m trying to make a living.”

Wilder’s acerbic humor and the visuals of film noir make for a peculiar if original black comedy. Consider the scene in which the pet chimp gets a midnight funeral, or Joe’s discomfited acquiescence to the role of gigolo; or Norma’s Mack Sennett-style “entertainments” for her uneasy lover; and at the ritualized solemnity of Norma’s “waxworks” card parties, which feature luminary has been, such as Buster Keaton.

Desmond’s lines, such as, “All right Mr. DeMille, I’m ready for my close-up,” and “I am big, it’s the pictures that got small!” are widely quoted. Much of the film’s wit is delivered through Desmond’s deadpan comments, which are often followed by sarcastic retorts from Gillis.

Desmond appears to not hear some of these comments, as she is absorbed by her own thoughts and in denial, and so some of Gillis’s lines are heard only by the audience, with Wilder blurring the line between the events and Gillis’s narration. Gillis’s response to Desmond’s cry that “the pictures got small” is a muttered reply, “I knew something was wrong with them.” Wilder often varies the structure, with Desmond taking Gillis’s comments seriously. When they discuss the overwrought script Desmond has been working on, Gillis observes, “They’ll love it in Pomona.” “They’ll love it everyplace,” Desmond says.

New Note: Opening Scene and Hitchcock’s Psycho

At a huge and majestic Sunset Blvd. mansion, the corpse of a man, Joe Gillis, floats in the swimming pool. In a long flashback, narrated by him with dark humor, Joe relates the events leading to his death. The end of the film reconstructs and thus explains the first scene, showing how Joe was killed by the madly jealous Norma Desmond when he departs her mansion, with two shots in the back, and a third, fatal one in the stomach, which throws him into the water. As he talks from his grave, the camera gets closer and closer to a semi-opened window, penetrating through the its curtains into the house. (Hitchcock improved and perfected this kind of opening shot in the first scene of Psycho, exactly ten years later).

Credits

Paramount

Produced by Charles Brackett.

Directed by Billy Wilder.

Screenplay by Brackett, Wilder and D. M. Marshman, Jr.

Cast

Joe Gillis (William Holden)

Norma Desmond (Gloria Swanson)

Max Von Mayerling (Erich von Stroheim)

Betty Schaefer (Nancy Olson)

Sheldrake (Fred Clark)

Morino (Lloyd Gough)

Artie Green (Jack Webb)

Undertaker (Franklyn Barnum)

First Finance Man (Larry Blake)

Second Finance Man (Charles Dayton)

Cameos by Cecil B. De Mille, Hedda Hopper, Buster Keaton, Anna Q. Nilsson, H. B. Wamer, Ray Evans, and Jay Livingston