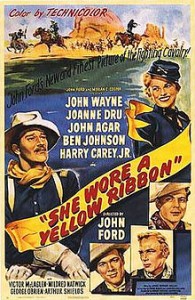

She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, John Ford’s Oscar-winning Western, one of the best he had made, offers John Wayne one of the richest parts he had played to date.

The tale takes place after the massacre of General Custer at the Little Big Horn.

A narrator sets the movie’s warm, rather sentimental tone, when he announces: “And wherever the flag rises over some lonely army post there may be one man–one captain–fated to wield the sword of destiny.”

That man is Wayne’s Captain Nathan Brittles, an elderly officer who has spent 40 years in service and is about to retire to civilian life in just a few hours.

When the Indians begin a war and Brittles wants to trail them, his Major objects. Instead, he assigns Brittles to escort his wife and daughter to a safer place, and Brittles reluctantly accepts.

At the station, Brittles is devastated by the sight of mutilated bodies, all victims of the Indian raid. “About time I did retire!” he tells himself. However, realizing that he has only four hours of service, he decides on a bold move against the Indians, outwitting them by stampeding their horses; humiliated and helpless, they sue for peace. Having turned a failure into a successful mission–the raid has no casualties–Brittles is now ready to retire.

The picture’s real hero, as in Ford’s Fort Apache, is not Brittles, the individual hero, but Brittles as a member of the larger collective he stands for, here, the Second Cavalry Regiment.

At the end of She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, the narrator tells the audience: “So here they are. The dog-faced soldiers, the regulars, the fifty-cent-a-day professionals riding the outposts of a nation. From Fort Reno to Fort Apache…from Sheridan to Stockton…they were all the same. Men in dirty-shirt blue…and only a cold page in the history books to mark their passing. But wherever they rose and whatever they sought for, that place became the United States.”

In this Western, the two-generational plot (a frequent element in Wayne’s movies) differs from that which defines Howard Hawks’ Red River, a film that was had been shot earlier but released in the same year. More nostalgic in his approach, Ford comments in his Western on the passing of heroes like Captain Brittles, an aging cavalry officer who has spent all his life in the army. Whereas Ford mythologizes the Old West and its honorable traditions, “Red River” looks ahead to the future and signifies social change.

Brittles doesn’t trust the younger generation and is reluctant to hand over the command to Lieutenant Flint Cohill (John Agar) because he lacks experience. Major Allshard (George O’brien) has to remind him that the youths have to learn the hard way, just as he himself had. Allshard protests that, “Every time Cohill gave an order, men would turn around and look at you, they’d wonder if he was doing the right thing.”

But in the end, the younger generation adopts Brittles’ way of life. Lieutenant Pennel (Harry Carey Jr.) decides to renounce an easy and comfortable life in the East in favor of military career, just like Brittles did and would do.

Some of the movie’s most touching sequences describe the ritualistic ceremonies in which tradition is transmitted from the older to the younger generation. On Brittles’ last review of his troops, he gets a present, a silver watch. Brings out his glasses, he sniffs back a tear as he reads the inscription, “Lest We Forget!” with a slight choke in his voice.

This is the only personal and informal interaction between Brittles and his men. It takes Brittles long time to soften, show his heart. Hence, only when he hands over the command to Cohill, Brittles calls him, for the first time, by his Christian name.

Though Wayne plays the lead, he is a member of a large ensemble of good actors, and two elements enrich the saga. The interaction that Wayne carries with his dead wife, visiting the graveyard, sharing ideas with her, talking to her.

Then there is a romantic triangle of sorts, at the center of which is Olivia Dandridge (Joanne Dru, who had also appeared in “Red River”), courted by two lieutenants, Pennell (Harry Carey Jr.) and Cohill. Brittles pokes fun at Pennell’s attempt to take Olivia for picnic. “Pic-nic-ing!” he says, emphasizing each and every vowel.

Brittles overrules the jealous Cohill by allowing Pennell to leave the fort, but then refuses Olivia permission to accompany him, because of the Indians. “You made a fool out of a couple of lieutenants,” he tells her, “That’s never against army regulations!””

Later on, when Brittles spots a yellow ribbon (A sign of having a woman), Brittles asks Olivia who is it for. “Why, for you, of course, Captain Brittles,” she replies, which makes him laugh. “For me! I’ll make these young bucks jealous.”

For the British scholar Allen Wells, She Wore a Yellow Ribbon is a better Western than “Stagecoach” or “The Searchers.” While I beg to disagree, there is no doubts that the movie is lovely to watch, and enjoyable. It offers a vivid portraiture of life on an isolated fort, depicted in warm and engaging mode.

The year of 1949 was a banner one for Wayne: He also excelled in the WWII drama, “Sands of Iwo Jima,” which garnered him his first Best Actor Oscar nomination and catapulted him to major box-office stardom.

The great cinematographer Winton Hoch, one of the few lensers to win the Oscar for the Western genre, also shot other Wayne features: Ford’s “Three Godfathers,” “The Quiet Man,” which won Oscars in 1952, “The Searchers,” and the non-Western “Jet Pilot,” Von Sternberg’s 1957 drama. He later also shot Wayne’s second directorial effort, “The Green Berets,” in 1968.

Oscar Nominations: 1

Cinematography (color): Winton Hoch

Oscar Awards: 1

Cinematography