Grade: A

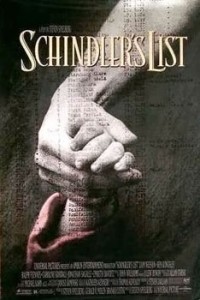

Steven Spielberg’s three-hour Holocaust epic, “Schindler’s List,” is his most serious and accomplished film to date, and probably one of the best Hollywood movies of the year.

I was a strong champion of the film at the annual meeting of the L.A. Film Critics Association, which honored Schindler’s List with its most prestigious citation: Best Picture.

Since then, two other groups, the N.Y. Film Critics Circle and the National Board of Review, voted it as best movie of the year, which makes it a top contender for the Oscar Awards. Who knows perhaps the Academy of Motion Picture will be able to “forgive” and “forget” the fact that Spielberg is the world’s most commercially successful filmmaker and finally honor him with its Best Director accolade.

Having taught courses on the Holocaust, I am quite familiar with the increasing body of books and films about it. Yet I have to admit that Spielberg’s movie caught me by surprise: It’s a serious, resonant, most effective work, which might be expected considering its amazing source material. But “Schindler’s List” is also a great movie that should serve as a companion piece to Claude Lanzmann’s landmark nine-hour-documentary, “Shoah” (1985).

I have recently reread Australian writer Thomas Keneally’s l982 book of the same title (the book enjoys now a new edition and a new popularity). Miraculously, Spielberg and screenwriter Stephen Zaillian have captured the book’s matter-of-fact approach and have also managed to contain innumerable details–the film is a huge canvas of locales, episodes and characters.

I have recently reread Australian writer Thomas Keneally’s l982 book of the same title (the book enjoys now a new edition and a new popularity). Miraculously, Spielberg and screenwriter Stephen Zaillian have captured the book’s matter-of-fact approach and have also managed to contain innumerable details–the film is a huge canvas of locales, episodes and characters.

The story begins as Oskar Schindler (Liam Neeson), a failed Nazi industrialist, takes over a major company that previously belonged to the Jews, and proposes to staff it with Jews–unpaid, of course. Schindler recruits a Jewish accountant, Itzhak Stern (Ben Kingsley), who soon becomes his right-hand man. Together, they supervise a plan that becomes a major supplier of pots and pans for the German military.

In the background is Krakow’s disintegrating Jewish community, whose members are forced to register and identify themselves as Jews. It is in these sequences that the film is most emotionally heartbreaking. The action switches from the liquidation of the Krakow ghetto and annihilation of a whole culture to the Jews’ confined life within the Plaszow Forced Labor Camp.

Schindler is depicted as a charmer, a persuasive man who knew how to manipulate the Nazi elite, but also willing to pay hard cash for every Jewish life saved. The most complex relationship in the film is between Schindler and Amon Goeth (Ralph Fiennes), the vicious commander of the camp. The filmmakers draw contrasts between the two: In one of their more personal encounters, the heavy-drinking Goeth expresses his admiration for Schindler’s moderate drinking, which he sees as control, and control equals power.

Schindler is depicted as a charmer, a persuasive man who knew how to manipulate the Nazi elite, but also willing to pay hard cash for every Jewish life saved. The most complex relationship in the film is between Schindler and Amon Goeth (Ralph Fiennes), the vicious commander of the camp. The filmmakers draw contrasts between the two: In one of their more personal encounters, the heavy-drinking Goeth expresses his admiration for Schindler’s moderate drinking, which he sees as control, and control equals power.

Residing in a luxurious castle located above the camp, Goeth observes the daily liquidation of Jews in a cool, dispassionate manner. In one of the film’s most excruciating scenes, Goeth is shooting innocent victims from a distance, from his balcony, as if he were practicing target shooting, or hunting birds in the wood.

The existential issues of life and death, who survived and who was exterminated, become a function of fate, coincidence–and sheer luck. In his attention to detail, Spielberg shows how some children actually survived: hiding in sleazy sewers, closets and basements, already crammed with other children.

Spielberg may be unfairly criticized for embracing Schindler’s point of view–unlike other Holocaust works, the movie tells the story of the Krakow ghetto and the Auschwitz concentration camp from Schindler’s vantage perspective, the way he perceived the events. At the same time, the portrait that screenwriter Zaillian paints of Schindler is far from heroic. There’s no attempt to whitewash his initial motivation to become wealthy and live a good life. In the midst of executions, Schindler is seen riding horses, eating a festive meal, or making love to a beautiful woman. However, gradually he begins to resent and register real feelings at the senseless crimes committed against the Jews. Ultimately, Schindler emerges as a multi-shaded character that is driven and torn by contradictory feelings.

Spielberg may be unfairly criticized for embracing Schindler’s point of view–unlike other Holocaust works, the movie tells the story of the Krakow ghetto and the Auschwitz concentration camp from Schindler’s vantage perspective, the way he perceived the events. At the same time, the portrait that screenwriter Zaillian paints of Schindler is far from heroic. There’s no attempt to whitewash his initial motivation to become wealthy and live a good life. In the midst of executions, Schindler is seen riding horses, eating a festive meal, or making love to a beautiful woman. However, gradually he begins to resent and register real feelings at the senseless crimes committed against the Jews. Ultimately, Schindler emerges as a multi-shaded character that is driven and torn by contradictory feelings.

Almost every frame of “Schindler’s List” demonstrates Spielberg’s anger and urge to chronicle a catastrophe that defies any logic or rational understanding. For once, Spielberg has found a worthy theme to which he applies his bravura technique. Spielberg’s signature kinetic style is very much in evidence with a mobile, often hand-held camera that dizzyingly, restlessly records the traumatic events.

The interesting black-and-white cinematography, by Polish artist Janusz Kaminski, chronicles the events with the fury of an ideologically impassioned documentary. Every once in a while the look changes from gritty realism to a more stylized look–an expressionist play of light and shadow that is impossible to achieve in color cinematography.

Many Israeli and Jewish actors were employed by Spielberg, which endows the work with more authentic looks and accents; for a change, you are not constantly reminded that you are watching American actors playing roles with more or less convincing dialects.

The film features three top-notch performances. Liam Neeson, a big, handsome actor, who has done some good work, is perfectly cast as the suave, always impeccably dressed Schindler. British actor Ben Kingsley also renders an effectively understated performance as the accountant Stern, one who almost reluctantly becomes Schindler’s employee–and later confidante and friend. But probably most impressive of all is Ralph Fiennes as Amon Goeth, the Nazi commander, whose full-bodied portrait goes way beyond the nasty German officers usually seen in American movies.

With all my enthusiasm for “Schindler’s List,” however, a number of weak scenes prevent the film from being perfect. Schindler’s emotional collapse after Germany’s defeat is too melodramatic and negates the otherwise matter-of-fact tonality of the film–and his personality.

And the very ending, in which Spielberg went to Israel and filmed the real survivors of Schindler’s List, is most touching but doesn’t belong to this movie.

Otherwise, the film displays as strikingly restrained style that is heartfelt without being schmaltzy. At the same time, I understand the motivation of Spielberg, as a mass-oriented entertainer, for including them, fearing that his tale might be too grim for the large public.

The film is shot in black and white, except for two brief scenes, in which a red coat is used to distinguish a little when Kraków ghetto is liquidated. Later in the film, Schindler sees her dead body, recognizable only by the red coat. Spielberg intended to symbolize how the U.S. government knew the Holocaust was occurring, yet did nothing to stop it. “It was as obvious as a little girl wearing a red coat, walking down the street, and yet nothing was done to bomb the German rail lines. s0 that was my message in letting that scene be in color.”

The inclusion of these two scenes in color met with varying reactions and interpretations. For some, it was crucial to indicate Schindler’s real change of values, when he sees her again. Others pointed to the different meanings of the color red: hope, love and innocence on the one hand, and blood and death on the other.

The greatest achievement of “Schindler’s List” is that on the one hand, it’s an enraged recording of annihilation of unparalleled proportions, of what Hannah Arendt most appropriately called the banality of evil. But the movie also contains a hopeful note, an unlikely proof of humanity: After all 1,100 Jews were saved by a Catholic German. This is what distinguishes, among other things, “Schindler’s List” from Alan Pakula’s “Sophie’s Choice.”

I usually go to see works about the Holocaust with trepidation, fearing that movies, especially Hollywood ones, might trivialize or cheapen the kind of disaster the Holocaust was. And there’s also the perpetual suspicion of “haven’t we seen all of that before” Or “is there really need for another Holocaust film” I am delighted to report that Spielberg categorically disproves both fears–there are actually new insights and facts about the Holocaust in his movie.