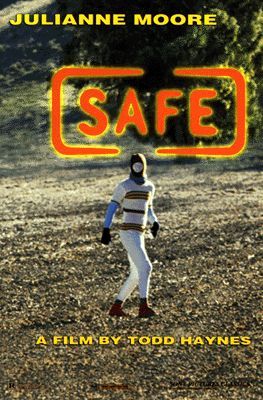

Precisely 25 years ago, Todd Haynes, then a beginning director, made Safe, an evocative film about an unnamed epidemic, which, unfortunately was misunderstood by some critics, and was not seen by many viewers.

Here is a chance to watch a major indie that has become prophetic in its view of an unseen enemy and its impact on our lives in terms of identity, isolation, alienation, and societal reactions.

My Original Essay

It took Haynes four years after his Sundance Film Fest award-winning Poison to get funding for his next feature, Safe.

Our grade: A- (**** out of *****)

Meanwhile, he made a short, “Dottie Gets Spanked,” for the ITV series, “Television Families.” A logical follow-up to “Poison,” the short revolves around an outsider, Steven, a boy who’s only six. Alienated from his surroundings, Steven is obsessed with the TV sitcom Dottie Frank, but his more distinctive (and perverse) trait is his interest in spanking as a form of authority and discipline. His true moments of happiness occur when Steven, alienated from his father due to his “inappropriate” interests, finds avenues of escape in solitude, drawing portraits of Dottie, and in public, when he visit the star’s TV settings. Haynes celebrates Steven’s new experience of gaining some control, when he purchases his naughty drawings.

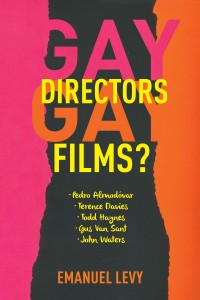

Note: Todd Haynes is the subject of my latest book, Gay Directors, Gay Films? (Columbia University Press)

World-premiering at the 1995 Sundance Film Festival, Safe signaled the arrival of a significant and original American voice. An emotionally devastating portrait of insulated domesticity, “Safe” centers on Carol White (played by Julianne Moore), a California San Fernando housewife who develops peculiar health problem, “environmental illness,” an all-encompassing allergy to chemicals. The problem, which baffles the medical establishment, has gained the moniker “the 20th Century Disease.” Carol’s immune system seems to be compromised. Defeated and helpless, Carol turns to a self-help organization, which then leads to an even greater isolation from the outside world.

An access into Carol’s bourgeois milieu opens the film, as the camera tracks through a car driven by the Whites a hill populated by houses that get increasingly larger and simulated in their design. This sequence is influenced by Haynes’ childhood in Encino, a suburb of Los Angeles, where architecture was “frightening, fake Tudor, fake country manor, everything fake.” For further inspiration, Haynes looked at films depicting Los Angeles as a futuristic city, where every trace of nature has been superseded by humans. Haynes perceives L.A. as an airport, because, as he said, “You never breathe real air. You’re never in any real place. You’re in a transitional, carpeted hum zone.”

Conventional cues that usually tell viewers how to respond to various situations and characters are either minimalized or altogether avoided. “Safe” breaks the Hollywood mold for emotional identification by not using close-ups and other audience-controlling devices. As is well-known, close-ups are Hollywood’s device for increasing the connection between the viewers and the characters, and more importantly between the viewers and the particular actors-stars who play them. Most of the narrative is shot through medium and long shots. Some shots are extremely long and static, as, for example when Carol goes to the drugstore in an impersonal mall, or when she visits the dry clean shop, where she experiences a major attack. The film also reduces psychological manipulation, letting viewers make up their own minds through their subjective perceptions. Like Van Sant, Haynes refuses to judge his characters, or subject them to ridicule, two conventional strategies of mainstream films.

The first scene depicts the selfish lovemaking of Carol’s husband Greg, to which she dutifully submits. Disregarding her erotic needs, he climaxes all too quickly, satisfying his immediate urge but ignoring his wife’s desire. Thus, from the start, Haynes chronicles Carol’s increasing loss of control in her desperate efforts to conform. This is also evident in the “”Bride of Frankenstein”-like perm she receives, and the fruit diet she adopts on a friend’s recommendation, all steps indicating Carol’s urge to accommodate, her strong need to conform and to blend in.

At the tale’s center is a rigorous dissection of Carol’s identity, her incessant need to be reaffirmed by others, usually dominant male figures. Watching the film, we are engaged in a two-phase process, first deconstructing Carol’s “old” and troubled identity, and then reconstructing Carol’s “new” but equally troubled identity. Haynes demands that we do the job, step by step, alongside him and Carol herself.

I disagree with critics who claim that as a character Carol is a blank, or an enigma. “Safe” avoids the psychological devices and cultural codes used in Hollywood’s character-driven dramas, but Haynes finds all kinds of unusual ways to relate basic information about Carol. For starters, Carol is primary defined by social class. She is utterly dependent on her Hispanic housekeepers, down to getting a glass of milk. Her role as homemaker means decorating the house and tending the garden. Even more important is her ritualistic farewell to her husband in the morning, and ritualistic greeting after waiting all day for his return from work in the evening.

Carol’s sense of aesthetics is conventional but precise; she seems to know exactly what she likes. In the course of the tale, she gets alarmed and annoyed on several occasions, but she really gets upset just once, when the wrong color (black) of furniture is delivered by mistake to her house. It’s the only proactive thing in which Carol engages, first complaining on the phone to the company, then paying a personal visit to the manager, demanding (politely) that the right couch is sent. She is attractive but her looks are bland, and they get blander and blander as the tale unfolds. Showing attention to minutiae detail, Haynes changes the color and style of Carol’s originally red hair from scene to scene, mirroring acutely the progression/regression of her persona.

Compared to more traditional films, “Safe” deliberately withholds background information about Carol until much later in the proceedings. There are no flashbacks to Carol’s past, and there are only two voice-over narrations, though both highly significant. In the first voice-over, she reads loud a letter she is writing to the Wrenwood center, in which she introduces herself and relates her social background. By her own admission, all her life, Carol, a Texan-born and bred girl wanted to fit in and live a normal life. We don’t know how she met her husband, Greg, and whether the marriage was based on love or pressure, self-imposed or from exerted by peers, to be attached. Carol is young enough to start a new family with children of her own, but she never expresses maternal instincts, and there are only a few scenes with her step son. The second voice-over comes at the end, also in the form of an enigmatic letter, which she writes to her husband and her stepson, relating her relative progress and welfare, over which we spectators cast serious doubts, based on what we have observed.

Haynes said that his main goal was to overcome the gap between himself as a director and Carol as a character, because otherwise she could have easily become a target for criticism–her bourgeois social class, her conventional tastes, her lack of knowledge and self-consciousness. The same even-handed approach is taken towards the New Age characters: “I wanted to challenge my own innate criticism of their world. I had no interest in condemning them, or placing myself above them.” At the same time, Haynes didn’t want Carol to become too attractive, or larger-than-life character, the kind of which she would have been in a typical Hollywood movie or teleplay.

Haynes wanted Carol to evoke the vulnerable, fractured nature of modern identity, an issue that American films have rarely addressed. Identity formation–how it is manipulated by larger social forces–is explored with subtle complexity. Like other women of her kind, Carol is not capable of breaking out of her prison-domestic milieu. “L.A. and Wrenwood both have isolation built into them, but both are telling you that you’re not alone, and that if you do these things, you’ll be affirmed as part of the group.” “Safe” shows the costs entailed in “joining help groups or giving up things in ourselves that can never be harnessed.”

Though refusing to indulge in a sappy style, on one level, “Safe” belongs to the tradition of “the woman’s film,” drawing on the melodramas of Douglas Sirk and F. W. Rainer Fassbinder. Haynes uses the melodramatic format to place limits on his narrative: Carol is enclosed in certain systems, whether it’s L.A. or another system. The measured rhythms of “Safe,” which are rigorous and austere, are conveyed by the anesthetic suburban spaces through which Carol moves: grand living rooms, cavernous car parks, clotted freeways, spotless spas. The film’s prevalent silence is disrupted by technological sounds, vacuum cleaners, television sets, radio station’s call-in, all indicators of how Carol’s identity, fragile in the first place, goes through an increasingly scary process, before alarmingly she shuts-down. It’s a process that inevitably leads her into a passive life of quiet desperation.

Carol fits the outline of Haynes’ protagonists in his other films, mostly victims rather than just products of their social contexts. Shaped by her environment, which is paddled by various kinds of patriarchs, Carol belongs to his series of plastic dolls. “Safe” raises provocative issues: Is Carol the problem? Is she yet another humorless version of a Stepford Wife, honed by aerobic drill instruction, looking like emaciated replicant, luminous pod, never, for example, breaking a sweat?

Filmed by Alex Nepomniaschy in wide-angle shots that reduce all human activity to miniaturized, doll-like movements, “Safe” is steeped in entrapment, paranoia, and malaise. To that extent, Haynes observes Carol coolly through a series of static deep-focus shots, placing her as an invisible woman who appears anesthetized in her materially comfortable but emotionally sterile life. Toward the end, covered from head to feet, using a mask that barely allows her to see or to breathe, Carol floats around the space slowly and quietly—as if she were an alien in a Stanley Kubrick sci-fi-horror film.

“Safe” plays on the “comfort and resolve” (Haynes’ words) format of the Television-Movie-of-the-Week. It subverts the rhetoric of recovery guru Peter Dunning, a “chemically sensitive person with AIDS,” to whom Carol turns for help at the Wrenwood retreat. In one subtle scene, looking more haggard than ever, though supposedly “adjusting” to Wrenwood, Carol is approached by Dunning who’s concerned over her reluctance to join in the group-think. Eager to fit in, Carol admits that she’s “still just learning the words.” Dunning sighs, “words are just the way we get to what’s true,” turning what she’s said into yet another essentialist statement. For Haynes, “words just show you how truth is unobtainable, because you can never articulate it.”

By insisting on pride, which equals self-blame, Dunning allows his patients to fail and fall, while his “therapeutic success” allows him to succeed and ascend. This is shown by the image of his majestic villa high on a hillside. Haynes wanted to examine the New Age philosophies of Louise Hay, the self-help author of “You Can Heal Your Life,” which led to the upsurge of similar treatments among many individuals, especially gay men with AIDS. “Safe” raises the questions of what is it about these philosophies that makes the sufferer of incurable illnesses feel more at peace? Why do we choose culpability over chaos?

Though not specifically identified, Carol’s illness has been interpreted by some as an analogy for the AIDS crisis, as a similarly uncomfortable and largely unspoken “threat” in 1980s Reaganomics America, which may explain why Haynes inserts a title card before the film begins that that story is set in 1987.

Dunning, one of few explicitly homosexual characters in Haynes’ work who’s already gay when we meet him, is a complicated man—intentionally problematized by the director. Though a self-proclaimed help guru, Peter fails to conform to easy categorization. At first, he appears to be Carol’s savior who can make her feel better by curing her chemical oversensitivity. But then Haynes deliberately undercuts Peter by suggesting that he might just be a self-absorbed and manipulative charlatan, perhaps even a fraud. The more patients the Wrenwood Center has, the better off he is materially. Peter, like other figures in Haynes’ oeuvre, is ultimately more conditioned by class, status, and power than by sexual orientation as a defining characteristic. We never see Peter’s private life or nocturnal activities; he may be asexual, preaching for love but abstaining from any erotic conduct, leading a sexless life.

The text’s subtlety, however, was mistaken by some viewers as formal endorsement of the new dubious fads, as if “Safe” were promoting New Age philosophies and places like Wrenwood, the Wellness Center. In actuality, “Safe” is critical of New Age therapies, perceiving them as a trap no better than the mindless materialism that had previously defined Carol’s life. The film is more of an indictment of New Age medicine than of California’s stifling bourgeois lifestyle. The chilling conclusion shows how Carol’s self-imposed exile is carried to an extreme. Standing in front of the mirror, with a blank expression on her face, Carol murmurs repeatedly, “I love you.” It is the biggest of the few close-ups that Haynes accords his (anti)heroine.

It’s a tribute to the film’s nuanced narrative and subtle tone that it doesn’t provide answers to these absorbing questions. The film ends with Carol retreating to her antiseptic, prison-like “safe room,” and whispering “I love you” to her reflection in the mirror. This ambiguous ending has evoked considerable debate among critics as to whether Carol has really emancipated herself, or simply traded one form of oppression, as a housewife, for an equally constricting identity, as a reclusive invalid and as a patient.

The scholar Julie Grossman has argued that Haynes made a film that challenges the traditional Hollywood narratives in which the heroine usually takes charge of her life. Instead, he sets Carol up as a victim both of a repressive male-dominated society and of an equally debilitating self-help, which is yet another male-dominated culture that encourages patients to take personal blame and responsibility for their illness.

Acclaimed by many critics, “Safe” was released by Sony Classic in June, as counter-programming to Hollywood’s commercial fare. Unfortunately, the film was commercially disappointment, grossing at the box-office about $500,000, even less than its low budget.

Nonetheless, “Safe” afforded the gifted Julianne Moore her first, much-admired leading role in a feature, and it gave Haynes a considerable measure of critical recognition.

In a “Village Voice” poll, “Safe” was chosen as one of the best American films of the 1990s!

Cast

Julianne Moore as Carol White

Peter Friedman as Peter Dunning

Xander Berkeley as Greg White

James LeGros as Chris

Susan Norman as Linda

Kate McGregor-Stewart as Claire

Mary Carver as Nell

Steven Gilborn as Dr Hubbard

April Grace as Susan

Lorna Scott as Marilyn

Jodie Markell as Anita

Brandon Cruz as Steve

Dean Norris as Mover

Jessica Harper as Joyce