George Cukor’s version of Shakespeare’s “Romeo and Juliet” could be classified as a curiousity item, a dignified effort that’s ultimately disappointing. Though more faithful to Shakespeare than other adaptations, the film is sharply uneven, only partially effective as a tale of passionate romance or as an opulent costume epic-drama.

Note:

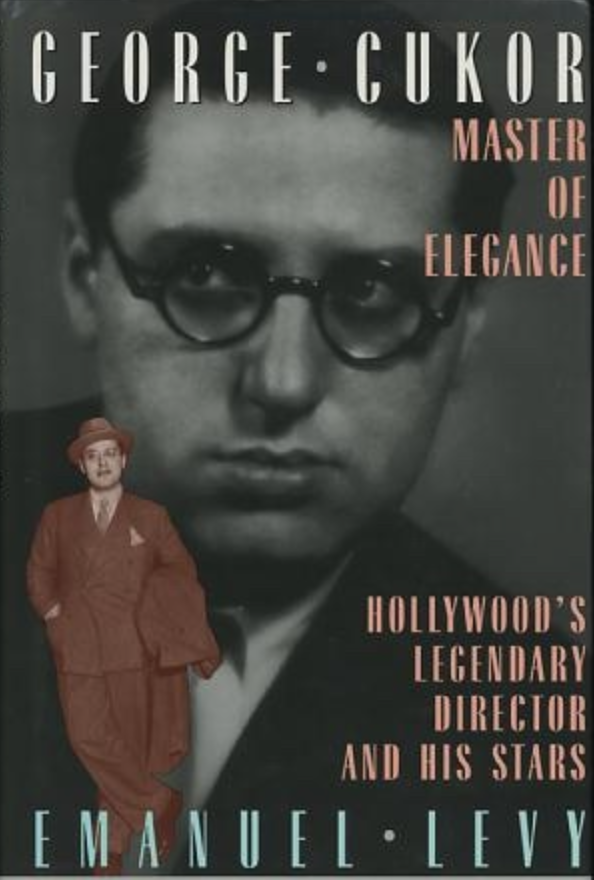

If you want to know more about this film and director, please ready my biography, George Cukor, Master of Elegance.

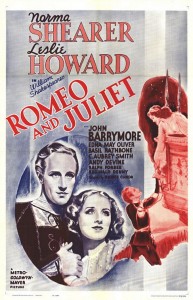

In June 1935, MGM’s production head Irving Thalberg announced his intention to stage Romeo and Juliet with his wife, Norma Shearer, under Cukor’s direction. Despite Louis B. Mayer’s objections, Thalberg argued convincingly that a good production of the classic, with rites and rituals and pageantry, would enhance the studio’s prestige in the public’ eye.

The film was finally approved by the top execs, but Thalberg was urged to keep the budget down, a challenge considering the scale of the sets and number od extras.

The casting of Romeo proved to be difficult, after Fredric March, Robert Donat, Franchot Tone, and Olivier, all declined the role. Cukor and Thalberg finally settled on Leslie Howard. Cukor was not particularly happy about his two leads, knowing that neither Howard nor Shearer could convincingly play the passionate, fiery young lovers–they were both too old and too stodgy. (Shearer also lacked classic training).

As a strategy, Cukor instructed his actors to grasp the cadence of Shakespeare, without speaking in an artificial classical manner; his goal was to make the language real and comprehensible to contemporary audiences.

As a strategy, Cukor instructed his actors to grasp the cadence of Shakespeare, without speaking in an artificial classical manner; his goal was to make the language real and comprehensible to contemporary audiences.

As a result, Shearer’s readings are clear and often elegant, but she’s not much of a dramatic actress, and her performance never rises above the mediocre.

her acting stood in sharp contrast to that of John Barrymore, who plays Mercutio in a grand, eloquent style.

A grand-scale production, Romeo and Juliet was Cukor’s biggest assignment to date. To that extent, he took greater care than the usual in his involvement in planning the medieval sets and costumes.

But he never concealed the fact that the prestige of the literary source material–it was the first and only Shakespeare Cukor ever directed–made him nervous and insecure.

Playwright Thornton Wilder was going to do a treatment of Romeo and Juliet, with samples of dialogue in modern adaptation. In the end, Talbott Jennings wrote the script, with a Cornell professor advising on how “to represent the best interests of the late author.”

Short on passion and compassion, this “Romeo and Juliet” is inhibited by MGM’s concept of “literary prestige.” The film is visually attractive but too stately for its own good. Cukor considered it his fault that the film lacked a “more genuinely Italian” look. It was one picture, he said, that if he would do it again, he’d get the “garlic and the Mediterranean” into it. Cukor later confessed that he failed to get his way at Metro about how a period picture should look and feel until he directed Garbo I Camille, his next movie (and much better on any level).

The disagreements–in fact, arguments and battles offscreen–among costume designer Adrian, resident art director Cedric Gibbons, and Oliver Messel, who designed the sets resulted in an incoherent look, pleasing no one at MGM.

The disagreements–in fact, arguments and battles offscreen–among costume designer Adrian, resident art director Cedric Gibbons, and Oliver Messel, who designed the sets resulted in an incoherent look, pleasing no one at MGM.

Original in isolated moments, like the ball scene, which was choreographed by the young Agnes DeMille, Romeo and Juliet is conventional at most others. Messel’s ideas were severely bullied by the studio’s art department–Cukor later regretted for not being more forceful with MGM, though at the time he lacked the clout for that.

When they shot the parting scene, Cukor thought that he managed to get touching and moving performances, but Irving Thalberg thought that the actors came across as “too glum.” “Irving,” Cukor said, “they’re partying in the morning.” “No,” said Thalberg, “it could and should be done with a smile.” Cukor saw his point and did another take–what Thalberg meant was tenderness, a more romantic way of saying goodbye.

Curiously, one of the best and most complex scenes, the potion scene, was shot with the least amount of trouble, in one take on a Saturday morning, while Thalberg had gone to the desert to work on the script of Camille.

Cukor made a crucial decision that the suicide scene should be done as one long, uninterrupted shot, beginning with Juliet’s mother leavings the room, continuing through Juliet’s long soliloquy, and culminating with the taking of the potion.

Shooting wrapped on May 7, 1936 and the picture was released on August 20. Romeo and Juliet was another movie running over two hours, but not by much. At that point, the negative costs of the opulent production had skyrocketed to over $2 million, way above Thalberg’s original $800,000 estimate.

With added costs of advertising and distribution, the film actually lost money at the box-office. It was one of Cukor’s few commercial flops in the 1930s. MGM reported a loss of $1 million, but Louis B. Mayer, the stingy studio head, did not make a bit fuss over it, as it became one of the last productions of Thalberg, who, in fact, passed away on the very night of the premiere.

But the response of the more literate viewers was favorable, and Cukor felt that overall his efforts were justified.

Still, Cukor wished he had given the exteriors of Romeo and Juliet a more distinctly Italian flavor, and at the same time, also made the interiors more intimate. Unlike other pictures he directed, Cukor continued to feel uncomfortable about this one; it represented an incomplete experience, with too many things he would have changed given the time and choice.

However, back in 1936, Cukor caught up in what he described as “NGM production gloss,” which meant giving the film a stately look. As a result, “Romeo and Juliet” is severely compromised, containing too much of the old Hollywood in it.

Oscar Nominations: 4

Picture, produced by Irving Thalberg

Actress: Norma Shearer

Supporting Actor: Basil Rathbone

Interior Decoration: Cedric Gibbons, Frederic Hope, and Edwin B. Willis

Oscar Awards: None

Oscar Context

Romeo and Juliet competed for the Best Picture with nine other films: Anthony Adverse, Dodsworth, The Great Ziegfeld (which won), Libeled Lady, Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, Romeo and Juliet, San Francisco, The Story of Louis Pasteur, A Tale of Two Cities, and Three Smart Girls.

In 1936, the Actress Oscar honored Luise Rainer for The Great Ziegfeld, the Supporting Actor Oscar went to Walter Brennan for Come and Get It, and to Art Direction to Richard Day for Dodsworth.

Cast

Norma Shearer as Juliet

Leslie Howard as Romeo

John Barrymore as Mercutio

Edna May Oliver as the Nurse

Basil Rathbone as Tybalt

C. Aubrey Smith as Lord Capulet

Andy Devine as Peter, a servant

Conway Tearle as Escalus – Prince of Verona

Ralph Forbes as Paris

Henry Kolker as Friar Laurence

Robert Warwick as Lord Montague

Virginia Hammond as Lady Montague

Reginald Denny as Benvolio

Violet Kemble-Cooper as Lady Capulet