Paris Is Burning returns to New York’s Film Forum, where it had originally premiered, for a two-week run, and will open July 5 in Los Angeles at Landmark’s Nuart Theatre, with a national roll out follow.

Almost 30 years after its initial release, Janus Films bring this landmark film back to theaters, in a new restoration supervised by director Jennie Livingston.

In 1991, Livingston, a Jewish, openly lesbian filmmaker set out to raise social consciousness about a little known subculture, motivated by ideas about the prevalence of gender-defined behavior, homophobia, and racism in mainstream American society.

The timing of the restoration and rerelease could not have been better: This month commemorates the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall riots and the rise of the gay rights movement.

It’s hard to imagine a more outcast group in American society than black and Hispanic homosexuals. Livingston’s landmark documentary, Paris Is Burning, shows how these groups, bound by common rejection, have constructed a subculture that has its own norms, values and language.

The film celebrates the vitality and resourcefulness of groups that are subcultural, i.e. part of the culture, without being countercultural, namely operating outside of and against dominant culture. The denizens of such cliques don’t so much wish to replace dominant culture, as they do long (or fantasize) to become members of the society they imitate–even if it means occupying marginal positions at its periphery.

The movie was made to prove that sexual identity is very much a product of social construction, of socialization, and as such can be either liberating or confining for some people, and sometimes both.

Upon getting a Yale University degree in literature, Livingston went on to become a photographer. Her earlier work has dealt with racism, sexism and the media. Frustrated with the “silence” of photography as an art form, Livingston then determined to do something more active and more overtly political. Paris Is Burning, her first film, fulfilled that wish. Like Barbara Kopple’s seminal docu, the Oscar-winner American Dream, and other socially relevant documentaries, Paris Is Burning is the kind of work that reveals the singular perspective of its author through the voices of her subjects.

Livingston was first exposed to the trend of voguing in 1985, when she observed a group performing at Washington Square Park in New York City. She had just arrived in the city to study film at the prestigious NYU Tisch School of the Arts.

It soon became clear to her that there were deeper socio-political messages in voguing than it seemed to appear on the surface. Intrigued by the participants’ game-playing, Livingston began to attend various “costume” balls, which challenged her (and mainstream culture) conventional ideas about the meanings of gender, race and class. The closer she got to know her “voyagers,” many of whom were adolescents or in their early twenties, the more she realized how articulate and creative they could be.

It took Livingston four long years to make the film, whose final cost was around $450,000. In 1985, Livingston met Meg McLagan, a videomaker and anthropologist, who introduced her to the Downtown Independent Cinema Movement.

Livingston was forced to sell her car, among other items, and to borrowed money in order to make a five-minute fund-raising trailer. She then applied and received two grants totaling $24,000 (from the New York State Council on the Arts and the Jerome Foundation), and further help from a TV producer. These grants were followed by an NEA grant, under the regime of Jesse Helms no less, just as he was beginning to rant about Robert Mapplethorpe’s audacious photography.

By 1987, Livingston had shot about 70 hours of footage from observing a diversity of balls and conducting interviews. She spent the next two years editing and cutting the film to a standard feature length. In 1989, the BBC came through with post-production funding, which helped her to complete the project.

By 1987, Livingston had shot about 70 hours of footage from observing a diversity of balls and conducting interviews. She spent the next two years editing and cutting the film to a standard feature length. In 1989, the BBC came through with post-production funding, which helped her to complete the project.

One of the most intriguing elements of Paris Is Burning is its revelation that style is the chief weapon used by transvestites and their entourages. Style is pervasive in speech, vocabulary, manner, dress and attitude. Style is a way of appearing to be “real,” a way of appearing to be something that one isn’t.

“Paris Is Burning” is the name of one drag ball that Livingston decided to explore in-depth as an anthropologist. She conducted interviews with some of the more notorious–“legendary” as they described themselves–self-styled queens. “I’ve been around now for two decades, reigning,” says Pepper Lebeija, one of the queens Livingston had studied. Pepper’s whole life revolved around the drag balls, which had much more to offer than simply the spectacle of men dressing up in women’s clothes.

Spanning a wide range, drag comes in all sizes, shapes and forms. The competition for prizes is fierce in various categories that call for the preparation of elaborate costumes. In the “Town and Country” Division, for example, contestants dress as upper-middle class men and women. Other prominent categories include Executive Realness (Wall Street), Military, and Schoolboy-Schoolgirl.

Paris Is Burning amounts to more than a record of an extravagant spectacle. The interviews reveal a whole new way of living, one that’s highly structured and self-protective. The structure consists of a system of houses where the young men first function as apprentices. Reflecting a minority coping with hatred, the houses usually represent intimate associations of friends, presided over by a type known as “mother” (like Pepper), that often provide a substitute for biological families.

Willi Ninja, the head of such a house, is an articulate man who’s also a master in “voguing,” in which dancers attempt to top each other by using gestures of high-fashion models. Related to voguing is “shade,” which is defined as the “verbal abuse, criticism and humiliation of a rival or competitor.” “Throwing shade” is what they do when they do it.

At the beginning of the film, the drag queens talk much in the manner of would-be Hollywood starlets. “The balls,” says Pepper, “are our fantasies of being superstars.” However, as the documentary progresses, the talk becomes more serious, somber, and melancholy. For instance, Carmen, a transsexual, discusses her operations, and Venus Xtravaganza, who is light-skinned and blond, dreams of finding Mr. Right.

Dorian Corey, an aging drag queen, is seen sitting in front of a mirror applying make-up. Once upon a time he said he he wanted to make his mark in the world, but now, he believes that he will have made his mark if he just gets through life.

A lot of common sense and wit are hidden behind their role-playing, but there’s also sadness as the transvestites go out of their ways to imitate the members of a society that will never accept them.

Drawing on one group’s reaction to a lifelong oppression, Paris Is Burning shows individuals who desire much more the cultural goals of fame, celebrity, and luxury than personal happiness. Livingston blames the brainwashing of advertisements that they see in the mass media for fostering unrealistic dreams and far-fetched yearnings.

As a social institution, the ball society embodies several unresolvable contradictions. Is it a manifestation of creative adaptation or identification with the aggressor. Is it the victim’s innocence or his refusal to be excluded from the culture of the rich and famous? Is the role-playing a genuine art or just passive mimicry?

Most of the voices in the film tend to express their creative energies by various ways of imitation. They insist that life, particularly when its meanings are drawn from magazines, movies, and TV soap operas, is about mass consumption and then more subjective interpretation. The film shows the devastating effects of living in a consumerist and materialistic society, and how one particular group responds in its own way to intense pressure for social conformity.

Paris Is Burning also exemplifies how African-American cultural expression–music and dance–has become co-opted and diluted for mass appeal. Drag queens have largely benefited from the media attention, which began with Madonna’s “Vogue” video, released long before Paris Is Burning hit theaters. In fact, several of the film’s subjects claim to have toured with Madonna and to have appeared in her famous video.

But some disturbing questions prevail: Was Madonna exploiting them for her benefit, or giving them an opportunity to work for some profit. The MTV voguing was packaged by Madonna for mainstream consumption. The film implies the conscious failure of mainstream culture to even acknowledge the role of the creative black genius that it has eagerly exploited.

Sociologically speaking, Paris Is Burning raises some persistentl unsettling questions about the fluidity of sexual identity and the tyranny of the mass media.

While praised by some critics for handling thorny problems, others have questioned the wisdom of bringing to light the spectacle of ghetto youth imitating bourgeois whiteness. In a critical article in Z magazine, bell hooks depicted the white, upper-middle class Livingston as an intrepid bwana, voyaging into the “heart of darkness,” in order to bring back African-American exotica mostly for white consumption.

Livingston has expressed her own disappointment by the reluctance of some gay organizations to back her feature. The Chicago Resource Center, a funding source for many gay projects, claimed that the movie did not meet their “criteria.” But Livingston charged back that the lack of funding was based on the fact that Paris Is Burning was not about a sector of gay society that gay organizations wanted to show and/or to promote. As she explained: “Poor black drag queens were not Harvey Milk, not a nice white guy you can bring home to mom.”

Being a white female filmmaker didn’t help matters either. Some feared that the film would be exploitative, or that there would be a backlash from the African-American and Latino communities. It is a known fact that drag queens have made00and continue to make–many gay indidviduals uncomfortable, to say the least.

For Livingston, one of the ironies lies in the fact that it was drag queens who actually had started the Stonewall riotts in June 1969, which launched the gay-rights movement. For her, the ideological and political dimensions of drag balls, in terms of class, race, and gender–were meant to be the focus of her feature.

Since the filmmaking spanned years, In the course of shooting the movie, the very voguing scene began to change, due to cultural cooptation and also due to the deteriorating climate of urban violence. One of the transvestites in the film was murdered on the streets during the shoot. And another, mummified body was found in the closet of a man after he had died of AIDS.

As a documentary about a politically charged subject, Paris Is Burning might never have found a distributor, had it not played to sell-out crowds for five months at New York’s Film Forum. The docu was later released by Miramax, which, with its notoriously shrewd and aggressive marketing, succeeded in making it into one of the most commercially successful documentaries ever made.

Artistic Status

Paris Is Burning shared the Grand Jury Prize for Best Documentary with Barbara Kopple’s American Dream at the 1990 Sundance Film Festival, and later won the Los Angeles Film Critics Best Documentary Award.

Note:

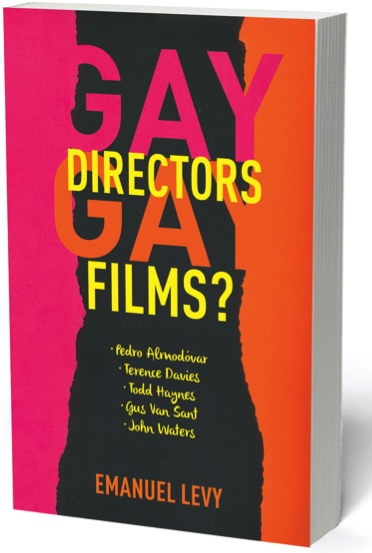

If you want to know more about gay directors and gay films, please read my new book:

Gay Directors, Gay Films? By Emanuel Levy (Columbia University Press)