The Idea for the Film

Every day in the newspapers we hear of these attacks. It’s such an extreme act that I began to think how could someone do that What could drive them to it I realized that we never hear the whole story. How could they justify this Not only to their families but also to themselves.

Researching the subject

I studied the interrogation transcripts of suicide bombers who had failed. I read Israeli official reports, and spoke to people who personally knew bombers who died, the friends, families, and mothers. What became clear was that none of the stories were the same.

The Film’s Producers

Bero Beyer, the Dutch producer, was from the beginning. The first co-producer on board was Lama Production’s Amir Harel from Tel Aviv, who produced “Walk on Water,” “Yossi and Jagger.” “Ford Transit” was screened at the Sundance Festival in January 2003, and it caught the eye of German producer Roman Paul from the Berlin-based Razor Film. Then the Paris-based Celluloid Dreams and Lumen Films came on board. During the 2003 Berlin Festival, we all met: a Palestinian director and a Dutch, two Germans and an Israeli and a French Producer. Exactly two years later, the film premiered at Berlin.

Assembling the International Crew

The crew consisted of people from Palestine, the Netherlands, Germany, France, Belgium, Israel and UK. We had Palestinian local crew and cast of about 50 people, a German crew of about 14 people, 4 French people, including the cameraman Antoine Heberl, 3 Dutch people, the actress who plays Suha, Lubna Azabal, is a Belgian citizen, a British crewmember, and for the shoot in Tel Aviv, we hired 10 additional Israeli crewmembers.

Casting the Three Leads

We had many casting sessions. The first session was more like a job interview with about 200 actors. I tried to figure out their personality and if they had charisma or presence. The actors I found close to the characters, I invited back to work with some scenes. Those that were able to add an extra layer to the characters, were the actors I chose. To finalize my decision, I had them acting together to see if they fit together on screen.

Shooting in Nablus, Nazareth and Tel Aviv

We had 3 months of pre-production in Nablus, during which the local cast and crew had to be found, and sets and locations had to be found and/or built. The main actors were brought in early to work as actual mechanics in Nablus in preparation. We shot in Nablus for 25 days, then had to move. In Nazareth, we shot another 15 days, mostly interiors and car scenes, but also The New Headquarter where Khaled is brought with Abu-Karem, and where they are all brought after the cemetery; Said and Suha in the car, talking about his father; the nighttime cemetery shot; Said in the restroom wiping off the sweat from under the belt; Said in the cab talking about water filters; the Othman checkpoint with many extras; and the olive grove.

Some sets had to be built to match with the original sets in Nablus, such as the exterior of Said’s house (the original was in an actual refugee camp) and the exterior of Khaled’s house (where Said comes asking for Khaled). Our production designer Olivier Meidinger did a tremendous, job and did it quickly, to build those on the spot. We finished with 2 1/2 days shooting in Tel Aviv.

Contingency Plan for Safety during the Shoot

We didn’t have a watertight plan, because such a thing is impossible in Nablus, but we had a security department. They advised us when and where to shoot. We were lucky to have some very good and courageous people working with us, who made sure we knew as much as was possible and could react as best as possible. From the moment it got dicey, all the cast and crew were briefed as much as possible. They all had the feeling they were dealing with a film worth being brave for.

It was kind of insane to shoot a film there. Every day we had some sort of trouble. Both the Israelis and Palestinians were used to news crews of a few people. But we didn’t have a small crew that could shoot film and run. There were 70 people and 30 trucks, making it impossible to run and hide.

Some thought we were making a film against the Palestinians, and others supported the film because they thought we were fighting for freedom and democracy. One group, though, thought the film was not presenting the suicide bombers in a good light and came to us with guns and asked us to stop. Not one day went by without our having to stop filming. We would stop and wait until the firing stopped and then start again.

Difficulties in Shooting in Nablus

To get into the area you have to work with the Israeli army, to survive inside the area you have to work with the Palestinians. Immediately, it’s a difficult task. To many, we were instantly suspicious. How did we get in with so many people and so much material Everybody wanted to read our script and many, not understanding what we were trying to do, drew different conclusions.

In Nablus, the Army invades the city almost everyday to arrest what they call the “Wanted” Palestinians. At daybreak, the invasion starts with tanks rolling in, gunshots and rocket attacks and in the evening there is a curfew. We had to report our whereabouts to these armed factions behind the backs of the Israeli Army, without them knowing we were in contact with them, because getting in and out of Nablus was difficult enough as it was. On top of this, the rivalry between Palestinian factions meant approval from one faction meant definite disapproval from the other. The rumor that we were doing something that was anti-suicide bombers was spreading fast, and one faction kidnapped our local location manager, Hassan Titi, and demanded that we leave Nablus.

Shooting Under Fire

One day, there was an Israeli missile attack on a nearby car, and gunmen ordered us to leave. This was the last straw for six of our European crewmembers. They left and I don’t blame them. They did the right thing. Life is more important than a film. We were too close to the destruction, and the situation was getting worse. Most of the real danger was from the missiles. When we heard shooting, we could go somewhere else, but you don’t see missiles coming. That is much more scary. So we had to stop the shooting, and I had a few dilemmas to deal with. How do I get my location manager back How can I stay friendly with the various Palestinian factions without the Israelis knowing about it and seeing me as one of them, risking another rocket attack Where do I find six professional crewmembers on such short notice, who I have to recruit by telling the reason why the others left

Dealing with Arafat

I decided to contact Prime Minister Yasser Arafat, although I never met him. I knew for a fact that Arafat had never visited a cinema. However, he did help us obtain the release of our location manager who was returned two hours later.

But I was torn with a new dilemma. Should we stay in Nablus or should we go If we left, we would justify the rumors that we were traitors. That would leave Hassan and the rest of our local crew who we would have to leave behind, as well as the factions that were on our side, in big trouble. If we stayed, we would have to continue working in a war zone and stand up against the rival factions. I decided to stay, it seemed the only option, but it created another dilemma; my producer Bero Beyer, wanted to leave. After a long fight, I suggested the following to Bero: I would start a campaign in town to stop the rumors, without upsetting the Army. In the meantime, the local and international journalists were about to turn the kidnapping into world news. We asked them to hold, because we were afraid of what that might do. The rival faction started a counter campaign. They were handing out pamphlets saying that we were an American/Spanish conspiracy. So we were outlawed. It seemed that with every step in the right direction, we were pushed back two steps. Every plan we made to resume the shoot got torpedoed.

After three weeks at a standstill, we resumed working again. Six new crewmembers were flown in and I continued, paranoid and under great stress, with my original plan: To direct a movie. Five days later, a land mine exploded 300 meters away from the set. We were running towards it; three young men died in the area we were shooting the night before, and the lead actress, Lubna Azabal, fainted. Though we wanted to continue filming in Nablus for continuity, we felt we had no other choice but to leave. We decided to move the set to my birth city Nazareth and leave Nablus for good.

We took these ridiculous risks to make sure the film would be as close to reality as much as possible, and to have an authentic look and feel. I understand why the Palestinian crew might do this, but I have wondered why the foreign crew would risk their lives.

Shooting on 35mm

It was a way of creating a distinction from the news footage that is on our television screens every day. While the film looks realistic, it’s still a film and tells a story. On the one hand, the film is fiction, and at the same time you want to it to ring true.

Shooting the Martyr Videos with Humor

The scene catches the heart of the film’s idea by simultaneously breaking down the martyrdom-heroism as well as the monster-evil, and making it human. Humans are often quite banal, but also funny and emotional. In real life, there often is comedy in the most tragic moments.

I shot the scene in a real location. This was one of the film’s concepts: Putting actors in the real surroundings in order to create a moment of truth. When Ali Suliman stands where real martyrs also stand giving their speech, he was so nervous, there was no need to act anymore. I was also nervous, because all around us, real organizers of these attacks were watching. I was very afraid they would get angry about the comedy in the scene. The entire cast and crew were nervous.

By the end of Take One, where Ali makes the speech, one of the organizers stopped us. I thought, “Now it is over.” But he just wanted to show Ali how to hold his gun correctly. There was no protest over the humor at all. Later, I realized that in reality things like this happen. It wasn’t irregular to them. By the way, Ali’s gun was theirs. We borrowed it. When Ali held it, knowing that this gun was used daily to aim at the Israeli Army, it had quite an impact on him.

Finishing the Production

After we finished, Francois Perrault-Alix, the gaffer, said to me: So much has happened; I don’t even know where to start when I get back to France. Usually I’ll have a few good stories after a shoot that will last a while in the local pub. But now, the amount of stories I have to tell will last for the next three years, but I don’t know where to start. And that’s how I feel. I look at my journal and realize there were so many stories happening every day and all worth telling. We were all, given all that had happened, exhausted and euphoric.

Anticipating Israeli and Jewish Reaction

I understand that my film will be upsetting to some that I have given a human face to the suicide bombers, but I am also very critical of the suicide bombers. The film is simply meant to open a discussion, hopefully a meaningful discussion, about the real issues at hand. I hope the film will succeed in stimulating thought. If you see the film, it’s obvious that it doesn’t condone the taking of lives. In my experience, with the film since it screened earlier this year in Berlin, much of the talk and protest comes from the idea of the film and not necessarily the film itself.

The full weight and complexity of the situation is impossible to show on film. No one side can claim a moral stance, because taking any life is not a moral action. The entire situation is outside of what we can call morality. If we didn’t believe that we were making something meaningful that could be part of a larger dialogue, we wouldn’t have gambled our lives in Nablus.

Hany Abu-Assad’s Biography

After studying and working as an airplane engineer in the Netherlands for years, Abu-Assad entered the world of cinema and television as a producer. He worked on TV program about foreign immigrants and documentaries like “Dar O Dar” for Channel 4 and “Long Days in Gaza” for the BBC. In 1992, Abu-Assad wrote and directed his first short film, “Paper House.” The film depicts the adventures of a thirteen-year-old Palestinian boy who tries to build his own house after his family’s house has been destroyed. “Paper House” was broadcasted by NOS Dutch TV and won several awards at film festivals.

Abu-Assad produced the feature film, “Curfew,” directed by Rashid Masharawi. An international co-production “Curfew” was highly praised, winning awards including the Gold Pyramid in Cairo, and the UNESCO Prize in Cannes, among others. After his second short, which he wrote, produced and directed, Abu-Assad began his first feature project as a director. He teamed up with writer Arnon Grunberg to develop a script that explored cinematic narrative and style in a comedy about a couple in Amsterdam. The film, “The Fourteenth Chick” was the opening night of the Netherlands Film Festival in Utrecht 1998 and was distributed by UIP.

Recent works include the bittersweet documentary “Nazareth 2000,” which Abu-Assad made for Dutch VPRO TV. The turmoil in a divided and secretly occupied city and its quarrelling Palestinian inhabitants, Christian and Muslim, is viewed through the eyes of two gas station attendants. Combining a kind and satirical approach to a serious subject matter, Abu-Assad succeeded in creating a multifaceted and surprisingly humorous documentary.

Since Augustus Film was founded by Abu-Asaad and Bero Beyer in 2000, Abu-Assad has directed “Rana’s Wedding” (2002), a production realized with the support of the Palestinian Film Foundation of the Ministry of Culture of the Palestinian National Authority. The film describes a day in the life of a young woman in Jerusalem, during which she tries to get married before four o’clock in the afternoon. Selected for Critics Week 2002 in Cannes, the film went on to win prizes at Montpellier, Marrakech, Bastia and Cologne.

Abu-Assad’s latest docu, “Ford Transit”(2002) played at Sundance. A portrait of a driver of a Ford Transit taxi, the film humorously observes the resilient inhabitants of Palestinian territories. The film won the FIPRESCI award at the Thessaloniki Festival, the In the Spirit of Freedom Award in Jerusalem, and together with “Rana’s Wedding,” the Nestor Almendros Award for courage in filmmaking at the Human Rights Film Festival in New York.

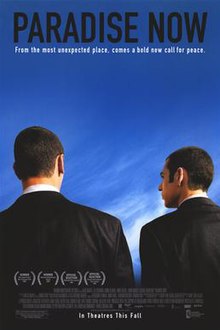

Abu-Assad and Beyer wrote “Paradise Now” in 1999 and shot the film in Nablus in 2004. It made its World Premiere at the Berlin Film Festival 2005, where it won the Blue Angel Award for Best European Film, the Berliner Morgenpost Readers’ Prize, and the Amnesty International Award for Best Film.

Credits

Directed, written by Hany Abu-Assad

Written by Hany Abu-Assad, Bero Beyer, Pierre Hodgson

Produced by Bero Beyer

Cinematography Antoine Héberlé

Edited by Sander Vos

Music by Jina Sumedi

Warner Independent Pictures (US and UK)

Release date: February 14, 2005

Running time: 91 minutes

Countries: Netherlands, Palestine, Germany, France

Languages Palestinian Arabic

Budget $ 2 000 000

Box office $ 3 579 902

Hany Abu-Assad’s Filmography

2005 — PARADISE NOW

2002 — FORD TRANSIT

2002 — RANA’S WEDDING

2000 — NAZARETH 2000

1998 — THE 14TH CHICK