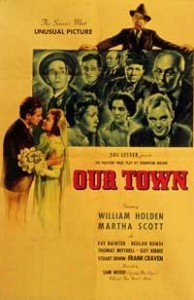

Directed by Sam Wood, the movie Our Town was based on Thornton Wilder’s 1938 play, which won the Pulitzer Prize for drama.

However, the New York Drama Critics Award was given that year to another work set in rural America, the stage adaptation of John Steinbeck’s book “Of Mice and Men.”

Grade: A- (**** out of *****)

“Our Town” proves to be one of the most enduring and most produced of American plays, but it is also one of the most misunderstood works. For some reason, it has evoked ridicule among some critics who charge that the play is too sentimental or too wholesome. While it may not be “a deadly cynical play, as playwright Lanford Wilson once has said, it is far from the simple, nostalgic hymn to small-town America at the turn of the century.

Moreover, contrary to many interpretations, the play (and film) is a testimony to an experimental vision at work.

Set in Grover’s Corners (modeled on the town of Peterborough, New Hampshire), the place is meant to stand for any small town. Indeed, a postcard addressed to a little girl locates the town in “the World, the Solar System, the Universe, the Mind of God.”

In this abstract, minimalist work, Wilder was interested in exploring the most universal elements of everyday life. How would a randomly chosen day look and feel in a town where supposedly “nothing happens,” where life is routine, a place where “nobody very remarkable ever come out of.”

Like other small-town films, “Our Town” is strategically situated in 1901, at the end of an era, just before the introduction of a most significant technological invention–the car. The movie captures the inevitability of technological change and its pervasive effects on people’s lives. The horse and buggy give way to the automobile, and the stable becomes a garage.

One can fault the film for ignoring the reality outside town, but this was a conscious choice by Wilder, attempting to conduct the theatrical equivalent of an experiment. Wilder examined the meanings of three fundamental principles of the life cycle, birth, marriage, and death, which also served as titles of the play’s three acts.

Covering a twelve-year-period (from 1901 to 1913) in the life of Grover’s Corner, “Our Town” illuminates the characters through a detailed attention to their seemingly humdrum lives. Of the three universal elements the movie examines, it is most concerned with death, or rather the influence of the dead on the living. Viewers are told, ahead of time, that Emily will die at childbirth, and that Mrs. Gibbs will die of pneumonia while visiting her daughter in Canton, Ohio. Joe, a bright boy who got a scholarship to M.I.T., will die in France during the First World War.

By the time the film was produced, everyday life in small towns was far removed from Wilder’s notion, but he wanted to evoke a bygone time and place. Stripping the essentials of life down to their most elementary principles, Wilder stresses the power of stoicism and endurance in the face of adversity, an idea not unlike Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life.

Soon after 1913, the druggist says, “the world began to shake and fidget. We shook with it, our town, I mean, but we’re still here.” And similarly to Frank Capra’s 1946 “It’s a Wonderful Life,” the movie hints at the restlessness of the town’s inhabitants and their wish to explore different worlds. Mrs. Gibbs would love to go to Paris. “Once in your life, before you die,” she says, “you ought to see a country where they don’t talk in English and don’t even want to.” Mrs. Webb suggests that Mrs. Gibbs “keep droppin’ hints” to her husband; that was how she got Mr. Webb to take her to see the Atlantic Ocean.

This conversation reflects the innocence and isolationism of American society prior to World War I, and the fear that exposure to new ideas might produce or increase the level of discontent with the small town.

Maintaining the play’s innovative format, the film is narrated by the town’s druggist, Morgan (Frank Craven), who introduces the characters and their backgrounds. The movie is set on June 7, 1901, just before the crack of dawn. The narrator is corrected by the history professor, that the town’s population is not 2,640, but 2,642. The doctor has just returned from Polish town, where he helped

Mrs. Goruslawski deliver twins.

The film also acknowledges the town’s ethnic diversity. “Cuttin’ across Main Street, across the tracks,” Morgan says, “is Polish town, foreign people that come to work.” The town is run by a Board of Selection, but no resentment is expressed over the fact that only males vote. The two households, the Gibbs and the Webbs, are friendly: their children, George Gibbs (William Holden) and Emily Webb (Martha Scott) are in love and destined to get married. George, the doctor’s son, doesn’t want to follow in his father’s footsteps; he wants to be a farmer. Family life is intimate and important; there is no competition from the mass media yet. In fact, the local newspaper, “Corner’s Grover Sentinel,” edited by Mr. Webb (Guy Kibbee), comes out only twice a week. The lack of mass media (radio, magazines, films) also means that knowledge is still transmitted orally from one generation to another.

Though respectful, the town’s women enjoy gossiping, here about the drinking problem of the church’s organist, Simon Stimson (possibly Wilder’s alter ego). But the gossip is not as malicious or harmful as in Alice Adams or Fury. “A very ordinary town,” Mr. Webb says, “we’ve got one or two drunks, but they’re always having remorse when an evangelist comes to town.” By and large, “likker ain’t a regular thing in the home here, except in the medicine chest…for snake bite.

With the exception of two digressions, the film is faithful to the play. First, it has scenery, to make the narrative more “realistic.” And second, the film deviates from the play by presenting a happy ending; in the movie Emily does not die. This cop-out finale almost undermines the poetry of the last act, which is a shame.

Wilder reportedly did not mind these changes and even supported the new resolution. In the film’s last scene, the narrator is on the bridge, it’s eleven o’clock. “Tomorrow’s another day,” says the narrator, but rather than reassurance, this statement evokes an ambiguous, open-ended question: Will tomorrow be the same kind of day as today?

Sam Wood’s film is as experimental and stylized as the play. Presented in brief scenes, “Our Town” does not abide by the conventions of a linear narrative text. Viewers are told the fate of the characters almost as soon as they are introduced. Shot in a stylized black and white by cinematographer William Cameron Menzies, there is good use of deep focus (one year before it was used by Orson Welles in “Citizen Kane”).

To create the right ambience, Wood employs creative dissolves, montages, and superimpositions; an image of Emily at present is superimposed on her as a younger woman. Flashbacks and asides are also utilized, as in the wedding scene, when the thoughts of George and Emily are conveyed (George tells himself he doesn’t want to get married).

A whole generation of playwrights was influenced by Wilder’s play. Arthur Miller, for example, believes that “Our Town” greatness lies in its focus on “the indestructibility, the everlastingness of the family and the community, its rhythm of life, its rootedness in the essentially safe cosmos despite troubles, wracks, and seemingly disastrous, but essentially temporary, dislocations.”

Cast

Mr. Morgan, the Narrator (Frank Morgan)

George Gibbs (William Holden)

Emily Webb (Martha Scott)

Mrs. Gibbs 9Fay Bainter)

Mrs. Webb (Beulah Bondi)

Dr. Gibbs (Thomas Mitchell)

Editor Webb (Guy Kibbee)

Howie Newsome (Stuart Erwin)

Simon Stinson (Philip Wood)

Mrs. Soames (Doro Merande)

Credits:

Directed by Sam Wood

Screenplay by Harry Chandlee, Frank Craven, Thornton Wilder, based on Our Town (1938 play) by Thornton Wilder

Produced by Sol Lesser

Cinematography Bert Glennon

Edited by Sherman Todd

Music by Aaron Copland

Production company: Sol Lesser Productions

Distributed by United Artists

Release date: May 24, 1940 (US)

Running time 90 minutes