Sacheen Littlefeather’s Claim to Native Ancestry Is More Complicated

Nearly a year and a half ago, the late Sacheen Littlefeather became the face of Native identity fraud when skepticism about her background was publicized shortly after her death in October 2022.

But newly publicized research indicates the late activist, most famous for her controversial and scandalous appearance at the 1973 Oscars, may have Indigenous roots after all.

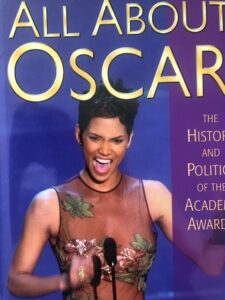

My Oscar Book:

One of her friends and former associates has come forward with genealogical records that indicate the activist best known for refusing Marlon Brando’s 1973 Oscar on his behalf may have had Indigenous ancestry after all.

Gayle Anne Kelley, whom Littlefeather approached to produce her 2018 documentary Sacheen: Breaking the Silence, commissioned private investigator to look into Littlefeather’s background after Native independent journalist Jacqueline Keeler (Diné/Dakota) published an explosive report in the San Francisco Chronicle alleging that she was not Apache and Yaqui on her father’s side, as she had claimed, but rather Mexican. That her mother’s side is white has never been disputed.

She enlisted Mark Pucci, a former NYPD detective and founder of nonprofit National Institute for Law & Justice. The two had been introduced a year earlier because of their respective work with Native communities — Kelley’s One Bowl banner has produced multiple films on the Haudenosaunee people, while NILJ’s caseload has focused on missing and murdered Indigenous relatives. Pucci tapped genealogist Kathleen Eddings to begin building the family tree of Sacheen Littlefeather, née Marie Cruz.

Keeler had traced the Cruz family line back to 1850, the time when Littlefeather’s four Mexican-born great-grandparents were born, to determine that none of them had connections to tribes in the U.S. Eddings furthered the search and found, one generation earlier, the baptismal records of a great-great-grandfather and his brother from 1819 and 1815, respectively, logged by two different priests in the Mexican state of Sonora, identifying their family as “Yaquis criollos de la tierra” — Yaquis raised from the land.

According to Keeler’s tree, the parents of Littlefeather’s great-grandmother Merced Gonzalez were surnamed Gonzalez and Lara; on Eddings’ tree, they are specified as Juan Antonio Gonzalez (the one with the 1819 baptismal record) and Yolanda Lara. “We’re not saying, ‘We’re right, you’re wrong,’ ” says Kelley. “We’re saying, ‘This is what we found.’ ”

However, Keeler says that the wording on Gonzalez’s record does not imply Indigenous ethnicity, and the family could have been Spanish migrants to the land. Even if Littlefeather did have Indigenous ancestry from Mexico, Keeler’s interest has always been in challenging her stated claims of Native American heritage.

“Native American doesn’t mean Mexican Indians. It means Native people whose lands are under occupation here in the 48 states by the United States of America,” Keeler says. She is focused on political and legal status (Littlefeather was never an enrolled member of a tribe) because of the heavy ramifications of that experience across generations. “If you’re not enrolled in tribe, you are not subject to Indian federal law [and] all of the trauma that happened under any of those terrible policies” such as the forced removal of Native children and placement into boarding schools and foster homes.

As with Buffy Sainte-Marie, another Oscars-related Native icon whose heritage is now cast into doubt, the pursuit of truth is fraught with complicated relationships colliding with the legacy of colonialism.

“Littlefeather came to us in the first place because she wanted to tell her story,” says Kelley, “this is the continuation of that on her behalf.”