Carl Franklin’s superb crime thriller, One False Move, blends elements of the noir genre’s fatalism, as in They Live by Night, with the drug-infused pathology of the procedural crime TV series, Miami Vice.

| One False Move | |

|---|---|

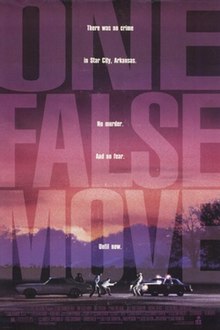

Theatrical release poster

|

|

Franklin tackles inherent American anxieties–interracial love, guilt, and denial–that have been ignored in mainstream movies. He shows mature understanding not only of his characters, but also of the dichotomies of city versus country, black and white, male and female.

Unlike other neo-noir features, One False Move is not just an exercise in style, it’s about real behavior–reckoning with one’s fate–and its inevitable consequences. The film deals with a perennial noir issue, the destructive grip of the past, the notion that one can try running from it, but one can never escape the past.

Blending gritty realism with stylized noir, co-writers Tom Epperson and Billy Bob Thornton have reinvented High Noon with its inevitable showdown between good and evil. What makes this film unusual is that the “action” is entirely driven by its characters: Ray (Bill Paxton), a white-trash Southerner, and Fantasia (Cynda Williams), his former black girlfriend and unbeknownst to him mother of his boy.

The film evoked controversy due to its uncompromising take on violence. Resenting the flippant way in which violence is handled in Hollywood movies–as glamorous and exhilarating–Franklin begins the movie with a drug rob out and the brutal slaughter of 7 people seen through the eyes of one of its victims. After the murder, the three killers hit the road to sell the drugs. Franklin captures the sordid desperation and anguished intimacy of people on the run. An encounter with a highway cop ends with another murder when Fantasia pulls the trigger. As they head South to her hometown, two L.A. detectives (one black, one white) follow them.

The critic David Denby has observed that Thornton and Epperson, who grew up in a small Arkansau town, know that in the South, whites and blacks aren’t as distant as they are in the North. In the South, whites and blacks co-exist–interracial relations are an intricate tangle of attraction and fear. Franklin brings out these ambiguities and tensions, which continue to build up to the last scene.

Structurally, the narrative makes good use of its central organizing principle: The trio.

Each of the film’s trio is racially mixed: the three killers; the two cops from L.A. and their Southern colleague; Fantasia, Ray, and their little boy; Fantasia, her brother and her son.

In each case, the trio is broken (often through death) so that a more balanced duo emerges at the end.

One False Move served notice that an exceptional filmmaker had arrived. In his previous films, Franklin proved a good actors’ director, based on his acting experience on TV’s A-Team and other shows. Franklin’s measured pacing and James L. Carter’s sharp cinematography give One False Move a bold look. With emotional honesty, Franklin shows stronger interest in characterizations and minute behavior than in conventional plot per se. Although the film works within the noir idiom, Franklin transcends the genre, reflecting his interest in “universal values of the black experience.”

The gratifying resolution, in which a wounded Ray is forced to recognize his black child (the only survivor in the mayhem that had killed his mother), lifts the film above ordinary despair with a chance of redemption.

The film’s decent budget of $2.5 million gave Franklin greater creative control and ability to achieve his vision.

However, despite rave revies, One False Move failed at the box-office.

Was the movie too violent?

In response to the claim that the film was excessively violent, Franklin told the “Observer,” “I didn’t want people getting excited seeing how neat someone can be killed. I want the audience to feel the emotional loss of life–the real violence is the loss, the violation of humanity. They’ve taken from us someone who had dreams, hopes, the same set of emotions we have.”

Cast

Bill Paxton as Dale “Hurricane” Dixon

Cynda Williams as Fantasia/Lila

Billy Bob Thornton as Ray Malcolm

Michael Beach as Pluto, aka Lane Franklin

Earl Billings as McFeely

Jim Metzler as Dud Cole

Credits:

Directed by Carl Franklin

Written by Billy Bob Thornton, Tom Epperson

Produced by Jesse Beaton, Ben Myron

Cinematography James L. Carter

Edited by Carole Kravetz

Music by Peter Haycock, Derek Holt, Terry Plumeri

Distributed by I.R.S. Releasing

Release date: May 8, 1992

Running time 105 minutes

Budget $2.5 million

Box office $1.5 million