Arthur Penn directed Night Moves, an uncompromisingly grim and despairing neo-noir, boasting a glorious cast, headed by Gene Hackman, Jennifer Warren, Susan Clark, and with supporting performances from Melanie Griffith and James Woods.

Grade: A (***** out of *****)

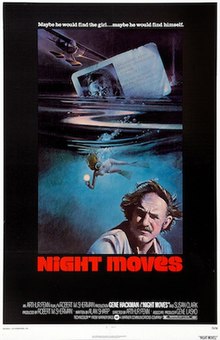

| Night Moves | |

|---|---|

Original theatrical poster

|

|

A neo-classic private eye, the tale centers on a Los Angeles private investigator who uncovers a series of sinister events while searching for the missing teenage daughter of a former movie actress.

The film is based on original screenplay by the Scottish writer Alan Sharp.

Night Moves’s original title, Dark Tower, had to be changed so as to not confuse it with the 1974 blockbuster The Towering Inferno.

Although Night Moves was not successful at the time of its release, it has attracted viewers and significant critical attention following its DVD releases. It is now considered a seminal modern noir work, reflective if the post-Vietnam era.

Harry Moseby is a retired professional football player now working as a private investigator in Los Angeles. He accidentally discovers that his wife Ellen is having an affair with Marty Heller.

Aging former actress Arlene Iverson hires Harry to find her teenage daughter, Delly Grastner. Long divorced from Delly’s father, a rich film producer, Arlene’s only income comes from her daughter’s trust fund, but it requires Delly to be living with her.

Arlene gives Harry the name of the guy Delly has been dating, a mechanic called Quentin. Quentin tells Harry that he last saw Delly at a New Mexico film location, where she started flirting with one of Arlene’s old flames, stuntman Marv Ellman. Harry realizes that the injuries to Quentin’s face are from fighting the stuntman and sympathizes with his bitterness towards Delly.

He travels to the film location and talks to Marv and stunt coordinator Joey Ziegler. Before returning to Los Angeles, Harry is surprised to see Quentin working on Marv’s stunt plane. Joey explains that Quentin is called in by the production company to tend to their stunt vehicles.

Delly ditched Quentin and shacked up with Marv, only to disappear again. Harry suspects that Delly may be trying to seduce her mother’s ex-lovers and travels to the Florida Keys, where her stepfather Tom Iverson lives. Harry finds Delly staying with Tom and his girlfriend Paula.

Tom hints that Delly has tried and possibly succeeded at being intimate with him and asks Harry to keep the law out of it. Paula is alternately sullen and flirty with both Harry and Tom, and she and Delly clearly don’t like each other. When Delly tries to make a pass at Harry by saying her shower isn’t working and asks to use his, Paula interferes and she and Harry bond over talking about Delly’s clumsy advances, as well as the chess game Harry is studying with his travel chess set, a game from 1922 in which a world-class champion missed seeing a play which would have won him the match.

Days later, Harry, Paula, and Delly take a boat trip to go night swimming, but Delly becomes distraught when she finds the submerged wreckage of a small plane with the decomposing body of the pilot inside.

Harry persuades Delly to return to her mother in California, as Tom doesn’t want her around anymore. After he drops her off at her mother’s home, he still is uneasy about the case, but focuses on patching up his own marriage. He tells his wife he will give up the agency, but then he learns that Delly has been killed in a car accident on a movie set.

He goes to the home of Arlene Iverson and finds her drunk by the pool, seemingly grief-stricken over her daughter’s death.

Harry tracks down Quentin, who denies being the killer, but tells him that Marv was the dead pilot in the plane and that he was involved in smuggling. Quentin manages to escape before Harry can learn more.

Back in Florida, Harry finds Quentin’s body floating in Tom’s dolphin pen. He accuses Tom of the murder; they fight, and Tom is knocked unconscious. Paula admits she did not report the dead body in the plane because the aircraft contained a valuable sculpture smuggled piecemeal from the Yucatan to the U.S.

Harry and Paula set off to retrieve the relic. While Paula is diving, a seaplane arrives and taxies over Paula, killing her. The explosion of Paula’s scuba tank knocks the seaplane off the pontoons, and as the cockpit submerges, Harry sees through the glass window that the drowning pilot is Joey Ziegler.

The last image is memorable: Harry, wounded and unable to reach the controls, unsuccessfully tries to steer the boat, which is now going in circles.

Night Moves was shot in 1973, but it was not released until 1975. Griffith’s nude scenes were filmed just before the release. They garnered particular controversy, due to the fact that she was only 17 at the time, even though she also appeared nude in Smile, released the same year.

The role of Ellen, played by Susan Clark, was originally offered to Faye Dunaway who turned it down to star in Chinatown.

An often-quoted line from Night Moves occurs when Moseby declines an invitation from his wife to see the movie My Night at Maud’s (1970): “I saw a Rohmer film once. It was kinda like watching paint dry.” Arthur Penn was an admirer of Rohmer’s film; its protagonist and Moseby have related opportunities for adultery, but respond differently.

One of the best psychological thrillers of the 1970s, the film has a shocking but poignant ending that’s fitting the predominantly harsh mood of the whole story. A deliberately murky, ambiguous variation on the more conventional private-eye themes.

Hackman was nominated for a BAFTA Award for his portrayal of private investigator Harry Moseby. This was yet another triumph for ever-busy, ever-versatile Gene Hackman.

Initially underestimated by critics and a box-office flop, Night Moves was reevaluated by critics many years after its release to the point of being deemed a cult classic of the era.

About Arthur Penn:

Penn directed some key pictures in the late 1960s and early 1970s: Bonnie and Clyde (1967), Alice’s Restaurant (1969), Little Big Man (1970), Night Moves (1975)), all of which captured the restless verve of the counterculture, its subsequent collapse, and the ensuing despair of the post-Watergate era.

Stephen Prince noted: Night Moves was a turning point in Penn’s career, his last carefully structured work, a strong and grim, whose bitterness emerges from an anxiety and from a loneliness that exists as a given, rather than a loneliness fought against, a fight that marks most of Penn’s best work. Night Moves is a film of impotence and despair, and it marks the end of a cycle of films.”

Cast

Gene Hackman as Harry Moseby

Susan Clark as Ellen Moseby

Jennifer Warren as Paula

Edward Binns as Joey Ziegler

Harris Yulin as Marty Heller

Kenneth Mars as Nick

Janet Ward as Arlene Iverson

James Woods as Quentin

Anthony Costello as Marv Ellman

John Crawford as Tom Iverson

Melanie Griffith as Delly Grastner

Ben Archibek as Charles

Credits:

Directed by Arthur Penn

Written by Alan Sharp

Produced by Robert M. Sherman

Cinematography Bruce Surtees

Edited by Dede Allen; Stephen A. Rotter (co-editor)

Music by Michael Small

Production companies: Hiller Productions, Ltd. – Layton

Distributed by Warner Bros.

Release dates: June 11, 1975 (NYC); July 2, 1975 (LA)

Running time: 99 minutes