And, of course, all the women who have played Wray’s role in future versions of King Kong, such as Jessica Lange in the 1976 version, Naomi Watts in Peter Jackson’s 2005 version, and Brie Larson in the 2017 Kong: Skull Island.

I wonder what kind of a tribute Wray would get when King Kong celebrates its centenary, in 11 years (in 2023).

King Kong in Context:

Wray appeared in more than 70 features, but her name will be always associated with one particular set piece.

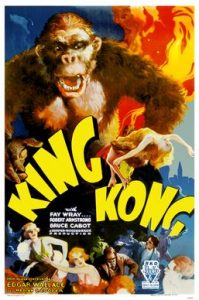

It is the climactic scene in the 1933 King Kong, in which the giant ape from Skull Island carries her to the top of the Empire State Building, gently places her on a ledge, lunges furiously at fighter planes peppering him with bullets and falls to his death from the 102-story skyscraper.

How and Why Fay Wray Was Cast

After the RKO board approved the King Kong test, producer Merian C. Cooper thought it was a good idea to cast the role of Ann Darrow with a blonde, as it would provide a sharper contrast to the gorilla’s dark pelt.

Wray was not the first choice, however. At one point or another, Dorothy Jordan, Jean Harlow, and Ginger Rogers were considered. But the role finally went to Wray, who was not legally blonde; she wore wig in the film.

Wray was inspired to accept the role more by Cooper’s vision and enthusiasm than by the quality of the script or the size and shape of her part.

In her autobiography, On the Other Hand, Wray recalls that Cooper had told her he planned to offer her a starring role opposite the “tallest, darkest leading man in Hollywood.” She assumed he was talking about Clark Gable or Gary Cooper–until he showed her a picture of Kong climbing the Empire State Building.

“She was a naturally gracious and witty person who charmed everyone who met her. She thought filmmaking was magical and loved being a part of the history of Hollywood,” said her daughter, former Writers Guild West president Victoria Riskin.

Wray was born September 15, 2007, on a farm in Alberta, Canada, and moved to Los Angeles as a teenager. She began frequenting studio-casting offices in her early teens, and landed occasional bit parts in film around 1919.

After acting in small parts, she began winning supporting roles. After graduating from the Hollywood High School, Wray became the ingenue in a half-dozen silent Westerns and played the bride in Erich von Stroheim’s 1928 silent classic The Wedding March.

Among her prominent sound films are “The Four Feathers” (1929), “Dirigible” (1931), “One Saturday Afternoon” (1933), opposite Gary Cooper, and “Viva Villa!” and “The Affairs of Cellini” (both in 1934).

Her damsel-in-distress depictions led to roles in other 1930s films in which her life, her virtue or both were imperiled: “Doctor X,” “Mystery of the Wax Museum,” “The Vampire Bat” and “The Most Dangerous Game,” co-starring Joel McCrea.

Among her leading men were such major stars as Gary Cooper, Ronald Colman, Fredric March, William Powell, and Richard Arlen.

It’s largely because of her role in King Kong that she would become a cult figure among cinema and nostalgia buffs, decades later in the 1960s and 1970s. (I “discovered” her when I saw a rerelease of King Kong at a rundown movie house in Tel Aviv circa 1970)

Before the VCR Revolution, King Kong was a staple program of film societies and revival houses. As an undergrad and grad film student at Columbia University, I have seen the film at least half a dozen times in such contexts.

Contrary to popular notions, despite its popularity, King Kong didn’t lead to a prominent career, as could be expected, and hence, Wray continued to make largely low-budget actioners.

Wray declined the offer to play a small part in the 1976 remake of “King Kong,” in which Jessica Lange was Kong’s co-star. She claimed that she disliked the script, and felt a remake could never equal the impact of the original.

In her 1989 autobiography, “On the Other Hand,” she described her many romances with writers, including her first husband, John Monk Saunders, whom she married at the young age of 19. A Rhodes scholar and screenwriter, known for such legendary films as Wings and The Dawn Patrol, he was a womanizer, an alcoholic and a drug addict.

Wray divorced him, she later said, after he injected her with drugs while she was sleeping. sold their house and their furniture and kept the money and disappeared for a time with their baby daughter. Saunders’s life ended tragically, when he hanged himself in 1940 at age 43.

Wray had a long romance with the noted playwright-scripter Clifford Odets.

In 1942, she was married to Robert Riskin, the Oscar-winning screenwriter of “It Happened One Night,” “Mr. Deeds Goes to Town” and “Lost Horizon.” He suffered a stroke in 1950 and died five years later.

After Riskin’s death, she married Sanford Rothenberg, a neurosurgeon, who had been one of Riskin’s doctors; Rothenberg died in 1991.

Wray retired in 1942, but she continued to make occasional movies in the 1950s.

She starred in the sitcom “The Pride of the Family” from 1953 to 1955.

In the mid-1950s, Wray appeared in mostly secondary roles in Hollywood films like “Small Town Girl” (1953), “The Cobweb” and “Queen Bee,” both in 1955, “Tammy and the Bachelor” (1957).

She finally retired from the big screen after “Summer Love” and “Dragstrip Riot,” both in 1958.

However, in 1979, she could not refuse an offer to appear with Henry Fonda in 1979 TV picture Gideon’s Trumpet.

Wray also wrote plays, some of which were produced in regional theaters all over the country.

Though she initially resented the way that King Kong has shaped and then dominated people’s perception of her as an actress, she eventually came to appreciate both the film and her place in Hollywood history because of that movie.

“I find it not acceptable when people blame Hollywood for the things that happened to them. Films are wonderful. I’ve had a beautiful life because of films,” she said in later years.

Wray died on August 7, 2004, at her Manhattan apartment. She was 96.