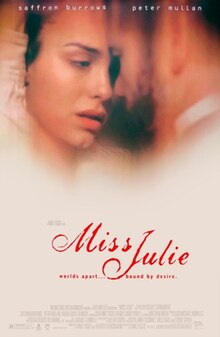

British director Mike Figgis continues his erratic, up-and-down-and-up career with Miss Julie, a solid, intermittently powerful but not great, screen adaptation of August Strindberg’s noted play about the turbulent, doomed relationship between a noble woman and her servant at the turn of the century Sweden.

Grade: B-

| Miss Julie | |

|---|---|

|

|

An intensely intimate drama for two, pic is toplined by a forceful performance from Peter Mulan (winner of the Cannes Fest acting prize for My Name Is Joe) and a so-so interpretation from Saffron Burrows in the lead.

Though not subscribing to either literary cinema or masterpiece theater traditions, this gloomy period piece is likely to be seen by arthouse patrons who are familiar with the play, but MGM/UA release faces tough times in persuading the larger public, including viewers who have embraced the big-screen adaptations of Henry James, Jane Austen, and E.M. Forster.

Strindberg wrote his boldly scandalous play, which was initially banned in several countries, in 1988, but Figgis sets his version, co-scripted with Helen Cooper, in 1894.

His rendition differs radically from the first film version, one of the early international arthouse hits, made in 1951 by the distinguished Swedish stage and film director Alf Sjoberg, also known as Ingmar Bergman’s mentor (and Garbo’s classmate).

On a large Swedish estate, the nobility lives in feudal splendor, in sharp contrast to the poverty of the peasants and servants. This is established in the very first sequence, which is mostly set in the kitchen, on a hot Midsummer’s Eve, while all the farm hands and servants are gathered for the traditional festivities. The empty kitchen is inhabited by the cook, Christine (Maria Doyle Kennedy), awaiting the arrival of her footman-fiancé Jean (Mullan).

The informal mood is interrupted as soon as Miss Julie (Burrows) invades the kitchen and orders Jean to wear her father’s formal jacket and dance with her. In what turns out to be one tumultuous and fateful night, Miss Julie and Jean engage in a dynamic, perverse role-playing that forces them to drop–and then assume again–the sharp class barriers of mistress-servant.

Strindberg’s bitter play is basically a psychological dissection of a beautiful but terribly complicated and repressed woman, who’s still influenced by the ideas of her domineering mother. What’s missing from Figgis’ version is a more detailed account of Julie’s childhood, how she was the unwanted daughter of a woman who clamored for freedom for sex and refused to marry the nobleman who wanted her, declaring she would only be his mistress. Julie’s mother lived in his house, unwillingly bore a girl, but raised and dressed her a boy, until finally her husband insisted on Julie’s return to full and legit girlhood.

What was great about Sjoberg’s film was its inventive flashback structure, which conveyed the characters’s lives as children, specifically how Jean the boy was infatuated by and fantasized about his mistress and her lifestyle. Moreover, in lieu of using dissolves or other conventional devices for the changing time scheme, Sjoberg showed in the same frame simultaneously the characters and their haunted memories.

Figgis, by contrast, concentrates on the here and now of the relationship, on how it changes radically in the course of the night, sometimes within a matter of seconds, culminating in sexual seduction (borderline rape by today’s standards), after which Jean demands that Julie steals her father’s money in help of his escape and future hotel plans. As the evening progresses, the despondent Julie shows alarming signs of her deep depression and unbalanced state of mind.

While the class warfare may be relevant today, the sexual battle and other Strindberg’s misogynist and misanthropic ideas seem outdated. Nonetheless, it’s worth noting that his sympathy with the underdog is not as clear-cut as it seems. Jean emerges as a greedy upwardly mobile footman, determined to improve his lot, consciously using every means in his possession, including his sexual potency. He exploits Julie’s weaknesses and vulnerability, continuously humiliating her, until he succeeds in pushing her towards self-destruction.

As always, Figgis tries to imbue his films with innovative techniques. The choice of a restless, hand-held camera is effective in conveying the shaky reality of the duo and its threat to collapse at any moment.

However, his decision to use split screen to depict the sex between Julie and Jean, showing them from a different angle, or showing Julie in different positions and from various distances, doesn’t gain much and manages to disperse the severity and fervor of these scenes.

Also suffering in comparison to the 1951 movie is Burrows’ uneven performance, albeit in an extremely demanding role that her predecessor, Anita Bjork, had played to perfection.

Mullan is more impressive but, again, doesn’t measure up to Ulf Palme’s illuminating rendition.

As the understanding and suffering cook, who’s in the background but her presence is very much felt, Kennedy lends competent support.

Tech credits, particularly Benoit Delhomme’s lensing, are good across the board.

Figgis’s adaptation is much longer than Sjoberg’s, mostly due to the overelaborate visual treatment (numerous cuts, close-ups and mega close-ups), that occasionally diffuse the claustrophobic intensity of the play.

Credits:

Directed by Mike Figgis

Written by Screenplay: Helen Cooper, Play: August Strindberg

Produced by Harriet Cruickshank, Figgis

Cinematography Benoît Delhomme

Edited by Matthew Wood

Music by Mike Figgis

Production company: United Artists

Distributed by MGM (Optimum Releasing in UK)

Release date: December 10, 1999

Running time: 103 minutes