Like other liberally curious, intellectually-bent youths who came of age in the 1960s, Gus Van Sant opened himself up to the subcultures of the Hippie and Beat Generations. He read and cherished such writers as the Beatnik Jack Kerouac (his seminal “On the Road”), the gay Jewish poet Allen Ginsberg (“Howl”), and especially the surreal, drug-infused literature of William S. Burroughs Jr. (“Naked Lunch”). Van Sant has never concealed his experimentation with drugs, as he confided in 1989: “Drugs played a big role in my life in the 1960s and 1970s, and I was pretty familiar with pot and LSD during that period.”

Grade: B+ (**** out of *****)

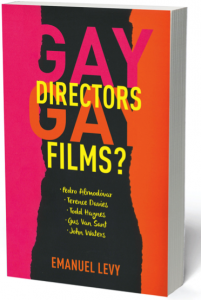

Like Almodovar, who is older by three years, Van Sant has made eighteen features to date, though unlike Almodovar and Haynes, at least half of Van Sant’s features are based on previously published sources, or scripts not written by him. As writer and director, he has adapted to the screen Tom Robbins’ novel, “Even Cowgirls Get the Blues,” which features a diverse cast (Keanu Reeves, Roseanne Barr, Uma Thurman, and k.d. lang). “My Own Private Idaho,” his most original and celebrated film, which featured two up-and-coming stars, Keanu Reeves and River Phoenix, also derives from existing sources on which he has unmistakably put his idiosyncratic signature.

Based on relatively low budgets, Van Sant’s movies have examined the lives of individuals who inhabit society’s underground. However, despite their bleak circumstances, his films display a nihilistic, often subtle humor, but decidedly not camp. Van Sant has made wildly subjective pictures that celebrate outsiders: illegal immigrants, male hustlers, dropouts, drugstore cowboys. In depicting drug addicts and male prostitutes, Van Sant has revealed their humanity without exploiting their tawdriness. His eccentric P.O.V. provides an intimate look at down-and-out characters–individuals on the fringes of society—that he neither glorifies nor condemns. He doesn’t expect his audience to take such a stance, either. It’s as if his camera were looking through a peephole, dropping in on secret lives and exposing their elements. Though drawn to realistic issues and grounded characters, Van Sant treats them playfully. The “Village Voice” critic Jim Hoberman has justifiably singled out, “the unabashed beatnik quality to Van Sant’s worldview.” Van Sant’s attraction to street youths and their sordid milieu is based on his belief that they are more interesting to observe, and that there’s more drama in their lives than is the case of bourgeois characters.

Based on relatively low budgets, Van Sant’s movies have examined the lives of individuals who inhabit society’s underground. However, despite their bleak circumstances, his films display a nihilistic, often subtle humor, but decidedly not camp. Van Sant has made wildly subjective pictures that celebrate outsiders: illegal immigrants, male hustlers, dropouts, drugstore cowboys. In depicting drug addicts and male prostitutes, Van Sant has revealed their humanity without exploiting their tawdriness. His eccentric P.O.V. provides an intimate look at down-and-out characters–individuals on the fringes of society—that he neither glorifies nor condemns. He doesn’t expect his audience to take such a stance, either. It’s as if his camera were looking through a peephole, dropping in on secret lives and exposing their elements. Though drawn to realistic issues and grounded characters, Van Sant treats them playfully. The “Village Voice” critic Jim Hoberman has justifiably singled out, “the unabashed beatnik quality to Van Sant’s worldview.” Van Sant’s attraction to street youths and their sordid milieu is based on his belief that they are more interesting to observe, and that there’s more drama in their lives than is the case of bourgeois characters.

In his first three films, which are thematically linked, Van Sant showed a natural lyrical touch and instinctive feel for recording lowlife, which is free of any judgment—there was neither condescension nor romanticizing.

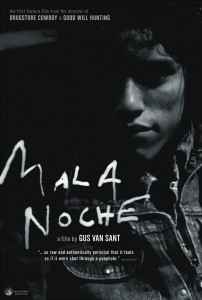

Van Sant’s first feature, “Mala Noche” (“Bad Night”), put him on the map of the then nascent independent cinema. “Mala Noche” follows the doomed infatuation of Walt (Streeter), a clerk in a skid-row convenience store, with the hunky Mexican immigrant and street hustler Johnny (played by the Native American Pueblo Indian Doug Cooeyate), who barely understands English. The film’s source material is a novella by Walt Curtis, a Portland street poet. Van Sant kept the manuscript, which was “sexually explicit like a dirty book,” under his bed for years, reading and rereading it, eagerly waiting for the time he could translate it into a personal film.

Van Sant’s first feature, “Mala Noche” (“Bad Night”), put him on the map of the then nascent independent cinema. “Mala Noche” follows the doomed infatuation of Walt (Streeter), a clerk in a skid-row convenience store, with the hunky Mexican immigrant and street hustler Johnny (played by the Native American Pueblo Indian Doug Cooeyate), who barely understands English. The film’s source material is a novella by Walt Curtis, a Portland street poet. Van Sant kept the manuscript, which was “sexually explicit like a dirty book,” under his bed for years, reading and rereading it, eagerly waiting for the time he could translate it into a personal film.

“Mala Noche” begins with images of outsiders, down-and-out characters in the marginalized section of Portland’s inner city. After the credits, there is a slogan, “If you fuck with the bull, you get the horn.” Walt, a thirtysomething white man who works as a liquor store manager, is a well-adjusted homosexual who likes the company of migrant workers. Van Sant cast local Portland figures in the leads that do not look like Hollywood actors playing male hustlers, such as the handsome Richard Gere in Paul Schrader’s glorified portraiture, “American Gigolo.” Thus, Walt is played by the plain, chubby, ordinary-looking Tim Street who’s a Seattle stage actor.

“Mala Noche” begins with images of outsiders, down-and-out characters in the marginalized section of Portland’s inner city. After the credits, there is a slogan, “If you fuck with the bull, you get the horn.” Walt, a thirtysomething white man who works as a liquor store manager, is a well-adjusted homosexual who likes the company of migrant workers. Van Sant cast local Portland figures in the leads that do not look like Hollywood actors playing male hustlers, such as the handsome Richard Gere in Paul Schrader’s glorified portraiture, “American Gigolo.” Thus, Walt is played by the plain, chubby, ordinary-looking Tim Street who’s a Seattle stage actor.

The main thread of the plot is Walt’s sexual attraction to Johnny, an illegal newcomer who wanders into his shop. Van Sant shows the Northwest landscape from Johnny’s P.O.V., first seen on a railroad boxcar. The narrative, which is slight in ideas but rich in imagery, unfolds as a variation of “amour fou,” a one-sided love by a mature Caucasian man, first infatuated and then obsessed with a Mexican youngster who doesn’t care about him. By standards of most characters in American cinema, Walt is a loser–he is unkempt, unshaven, wearing an old and dirty raincoat, spending hours in seedy bars drinking. He proudly declares to a female friend: “I’m in love with this boy. I don’t care even if it jeopardizes working at the store. I have to show him I’m gay for him.”

The main thread of the plot is Walt’s sexual attraction to Johnny, an illegal newcomer who wanders into his shop. Van Sant shows the Northwest landscape from Johnny’s P.O.V., first seen on a railroad boxcar. The narrative, which is slight in ideas but rich in imagery, unfolds as a variation of “amour fou,” a one-sided love by a mature Caucasian man, first infatuated and then obsessed with a Mexican youngster who doesn’t care about him. By standards of most characters in American cinema, Walt is a loser–he is unkempt, unshaven, wearing an old and dirty raincoat, spending hours in seedy bars drinking. He proudly declares to a female friend: “I’m in love with this boy. I don’t care even if it jeopardizes working at the store. I have to show him I’m gay for him.”

Johnny, like other runaways and street hustlers, enjoys playing with his buddies in a video arcade. Insisting he is straight, Johnny says he doesn’t like “putos,” a pejorative term for homosexuals; the Spaniard Almodovar uses the equally pejorative term “maricones.” Nonetheless, Johnny makes exceptions if the gringos have money–cash money–and cars. Socializing with white gay men is tolerated so long as they provide materialistic favors, functioning as “friends with benefits.” Essentially, Johnny exploits Walt, eating at his expense, driving around in his car. Never mind that the vehicle is ramshackle, it still enables Johnny to show off to his Mexican mates, who are poorer than him.

Johnny, like other runaways and street hustlers, enjoys playing with his buddies in a video arcade. Insisting he is straight, Johnny says he doesn’t like “putos,” a pejorative term for homosexuals; the Spaniard Almodovar uses the equally pejorative term “maricones.” Nonetheless, Johnny makes exceptions if the gringos have money–cash money–and cars. Socializing with white gay men is tolerated so long as they provide materialistic favors, functioning as “friends with benefits.” Essentially, Johnny exploits Walt, eating at his expense, driving around in his car. Never mind that the vehicle is ramshackle, it still enables Johnny to show off to his Mexican mates, who are poorer than him.

Johnny’s closest buddy is Roberto, nicknamed Pepper, played by the local amateur boxer, Ray Mongue. Based on mutual exploitation, the relationship between Walt, as the older mentor-tutor, and Johnny and Pepper, as the uneducated but desirable simpletons, is peculiar, to say the least. It is defined by occasional sexual encounters, and laced with touches of sado-masochism. When Walt allows Pepper to drive his car, the boy proves to be a lousy driver, landing the car in a ditch, despite Walt’s careful instruction. “You drive like you fuck,” the exasperated Walt says.

When Johnny mysteriously disappears, Walt switches his attention to Pepper, taking care of him when he is ill, trying to have sex with him (in any position Pepper consents to). Melodrama kicks in, when the police arrives at Walt’s place, and Pepper, afraid of being deported, attempts to flee with a stolen gun in his hand, forcing the police to shoot him. All that Walt can do is hold the dead boy in his arms.

In the next sequence, Walt spots Johnny, who had been sent back to Mexico as an illegal alien, but managed to come back to Portland. Their friendship resumes, until Johnny finds out about Pepper’s death, for which he unfairly blames Walt. Rushing out in anger, he writes ‘puto” on Walt’s door and leaves. Unfazed, the passive-aggressive Walt continues to pursue Johnny, and the tale ends ambiguously with Walt driving down the street.

In the next sequence, Walt spots Johnny, who had been sent back to Mexico as an illegal alien, but managed to come back to Portland. Their friendship resumes, until Johnny finds out about Pepper’s death, for which he unfairly blames Walt. Rushing out in anger, he writes ‘puto” on Walt’s door and leaves. Unfazed, the passive-aggressive Walt continues to pursue Johnny, and the tale ends ambiguously with Walt driving down the street.

It’s hard to describe Walt’s encounters with Pepper as real love-making, reflecting Van San’t shy personality, conservative upbringing, and the refusal of his “actors” to be shown naked, or engaged in explicit sexual positions. There’s extreme cautiousness in showing briefly frontal nudity, when Walt strips off his clothes. Van Sant just shows Pepper spread on a sleeping bag on the floor. Through meticulous editing and darkly-shadowed intercuts, Van Sant creates the illusion of intercourse, focusing on the participants’ faces rather than bodies. As director, he didn’t like the way sex was depicted in Hollywood movies, because “a lot of times sex scenes become a bumping and grinding activity, which is not particularly sexy.”[iii] This ultra-careful approach to sex would continue to characterize Van Sant’s films, even when they concern straight love-making, such as the oral sex between Nicole Kidman and Joaquin Phoenix in “To Die For.”

Van Sant’s motivation behind “Mala Noche” was to make an honest, non-judgmental movie about a subject that mainstream Hollywood would never touch. Self-financed, the film was shot on cut-rate stock in black-and-white. The meager $25,000 budget came from Van Sant’s savings after years of working at an advertising agency in New York. Low as its price was, however, it took almost a decade for the low-budgeter to recoup its expense.

Van Sant’s motivation behind “Mala Noche” was to make an honest, non-judgmental movie about a subject that mainstream Hollywood would never touch. Self-financed, the film was shot on cut-rate stock in black-and-white. The meager $25,000 budget came from Van Sant’s savings after years of working at an advertising agency in New York. Low as its price was, however, it took almost a decade for the low-budgeter to recoup its expense.

Van Sant said that “Mala Noche” was inspired, among other things, by the commercial appeal of the 1981 gay movie, “Taxi Zum Klo” (“Taxi to the Toilet”), which screened at the New York Film Festival and then played commercially in New York’s Cinema Studio (my neighborhood) for six months.[iv] In that personal movie, the German director Frank Ripploe chronicles in graphic detail and with dark yet realistic humor, the sexual adventures of a gay schoolteacher in West Berlin. The film culminates boldly with the teacher’s coming out (in drag) in front of his pupils in class. Other artistic influences on van Sant included David Lynch, who shot his first two movies, the underground “Eraserhead” in 1977, and the 1980 studio-financed, star-driven “The Elephant Man,” in heightened black-and-white contrasts. Lynch’s 1977 AFI-made debut was particularly influential in its lighting style and expressionist visuals. “Mala Noche” contains expressive close-ups of Mexican youths, dark shots of ashtrays, cigarettes, and smoke, and other images that fit into the tale’s nocturnal nature.

The locations in “Mala Noche” are the grim sites of Portland’s Burnside region: Shabby buildings, rundown motels, cheap grocery stores, filthy streets. Mixing distinctive exterior vistas of the Pacific Northwestern with nihilistic, darkly humorous sensibility marked the arrival of an exciting talent. The “New Yorker” critic Pauline Kael singled out the “authentic grungy beauty,” and its “wonderfully fluid grainy look,” which she found expressionist yet made with improvised feel that recall Jean Genet’s short film, “Un Chant D’Amour.” (Genet proved to be inspirational figure to all the filmmakers in my book). “Mala Noche” received scant attention before winning the L.A. Film Critics Association Award for Best Independent Film, in appreciation of its authentically personal nature. This recognition emphasized the importance of critics for the promotion of esoteric fare, turning “Mala Noche” into a staple of the festival and art-house circuits.

It took years for “Mala Noche” to get a legit theatrical distribution beyond the festival circuit, in December 1989 to be exact. By that time, Van Sant was already in his late 30s and about to release his next feature, “Drugstore Cowboy.” Following Kael, the other critics responded favorably, as evident in Peter Rainer, a Kael protégé, in his review: “The ardor in this film isn’t only in its love story; it’s also in Van Sant’s experimental, poetic use of the medium.” Rainer stated that “Van Sant can’t pretend true nihilism, because he is too enraptured in the possibilities of his new-found art.” Other critics also singled out Van Sant’s penchant for depicting the romanticism of losers, without succumbing to soft-headedness or sentimentalism. In the “Washington Post,” Hal Hinson observed: “Van Sant is fascinated by the poetic allure of poor beautiful boys riding the rail into the Promised Land and ending up dead, crumpled on the pavement in the middle of a street, thousands of miles away from home.”

“Mala Noche” still remains a model of film grunge for young independent directors. The film displays ideas and themes that would recur in Van Sant’s future works: unfulfilled love, unrequited romantic yearning, and a vivid sense of life’s ironies and absurdities. Most relevant to this book’s concerns is Van Sant’s refusal, from the beginning of his career, to treat homosexuality (and sexual orientation) as a “problem,” or a phenomenon that needs to be discussed or judged—in any explicit way. The sexual orientation (lesbians and straights included), sexual practices, and sexual identities of his characters are taken as given, alongside other social attributes. In “Mala Noche,” Johnny and Pepper’s Mexican backgrounds, minority status, social class, and outsiders’ position are more important than whether or not they sleep with Walt, or how they perceive themselves sexually. Van Sant doesn’t define Johnny or Pepper as male prostitutes; they are just street hustlers who would sleep with anyone for a few bucks.

Earning acclaim beyond the festival circuit, “Mala Noche” soon attracted Hollywood attention, and Van Sant was courted by the major studios, such as Universal. He pitched some ideas (“Drugstore Cowboy” and “My Own Private Idaho”), but the established companies showed no interest.