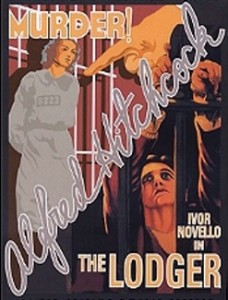

While the silent The Lodger was not Hitchcock’s first film—it was actually his third—this work was the first to be designated by critics and by himself as a “typically Hitchcockian Picture.”

Grade: B (***1/2* out of *****)

It demonstrates his trademark of bravura technical skills, witty humor, and fluent and suspenseful storytelling.

Hitchcock told French director Francois Truffaut in his long interview-book: “This was the first picture influenced by my period in Germany. In truth, you might almost say that ‘The Lodger’ was my first picture.”

In “The Lodger” (subtitled “A Story of the London Fog”) British matinee idol Ivor Novello plays Jonathan Drew, a quiet, secretive young man who rents a room in a London boarding house. Drew’s arrival coincides with the reign of terror orchestrated by Jack the Ripper.

As the tale progresses, with steady tension and mounting suspense, circumstantial evidence begins to mount pointing to Drew as the Ripper.

Telling much of its story in visual terms, “The Lodger” contains some bold special effects. It introduced a theme that would reappear in many of the director’s films: mistaken identity, an innocent man accused of a crime he did not commit, an ordinary (every)man caught in a web of extraordinary events.

Hitchcock’s First Cameo

“The Lodger” was also the first film in which Hitchcock made a personal appearance as an extra; he claimed that he just needed another body to fill the frame. This momentary personal appearance later became a Hitchcock trademark, a career‑long habit initially motivated by superstition and later continued as a signature, a gag, and marketing tool.

Hitchcock was dissatisfied with the ending of “The Lodger,” which was dictated by the fact (or myth) that popular stars like Ivor Novello could never be cast as villains due to their established public screen image.

The same compromised conclusion would be imposed on Hitchcock’s 1941 American film, “Suspicion,” due to the fact that its hero was played by star Cary Grant. If it depended on him, Hitchcock later said, he would have ended “The Lodger” on a more ambiguous note, like the lodger disappearing into the foggy night, without establishing clearly either his innocence or guilt.

There are other thematic similarities between “The Lodger” and the more polished Hollywood thriller, “Suspicion,” which was nominated for the 1941 Best Picture.

Even so, the above ending helps to signify Hitchcock’s stronger interest in showing the deviant and criminal tendencies that may exist within presumably innocent characters, rather than the more conventional theme of devoting the story to the pursuit and successful unveiling a crime and its perpetrator.

Hitchcock presents a compelling portraiture of an insanely jealous police detective, a man who’s supposed to represent the law, and the inner and outer workings of this jealousy to the point of revenge. In theme and ideology, Hitchcock was well ahead of Hollywood movies in depicting severely flawed cops and detectives, presumably keepers of the law.

The scholar Donald Spoto has pointed out the movie’s effective use of staircases and cellars, visual and spatial motifs that would recur in many Hitchcock future movies, such as “Rebecca,” “Suspicion.” Notorious,” and of course “Psycho.”

Remakes:

In 1944, John Brahm, better known for his melodramas and “women’s pictures,” directed a Hollywood version of “The Lodger,” starring Laird Cregar. Some critics consider Brahm’s version to be a better, more chilling feature about the bloody Jack the Ripper, largely due to its effectively recreated atmosphere of Victorian London.

The Lodger was remade again in 1953 as “Man in the Attic,” with Jack Palance in the lead.

Cast

Marie Ault as The Landlady (Mrs. Bunting)

Arthur Chesney as her Husband (Mr. Bunting)

June Tripp as Daisy Bunting, a Model

Malcolm Keen as Joe Chandler

Ivor Novello as Jonathan Drew (The Lodger)

Eve Gray as Showgirl Victim (uncredited)

Alfred Hitchcock as Extra in newspaper office (uncredited)

Reginald Gardiner as Dancer at Ball (uncredited)

Alma Reville as Woman Listening to Wireless (uncredited)

Credits:

Directed by Alfred Hitchcock

Produced by Michael Balcon, Carlyle Blackwell, C. M. Woolf

Screenplay by Eliot Stannard, based on The Lodger by Marie Belloc Lowndes

Cinematography: Gaetano di Ventimiglia

Edited by Ivor Montagu

Production company: Gainsborough Pictures

Distributed by Woolf & Freedman Film Service (UK); Artlee Pictures (USA)

Release date February 14, 1927 (UK);

Running time: 75 minutes (original); 90 minutes (2012 restoration)

Hitchcock Biography (U.K. era, Up to 1939)

Born on August 13, 1899, London, the son of a poultry dealer and fruit importer, died 1980. The family was Catholic, and Alfred was enrolled at a Jesuit school, London’s St. Ignatius College, at a young age. He later attended the School of Engineering and Navigation, where he studied mechanics, electricity, acoustics, and navigation.

At 19, he entered the job market as a technical estimator of electric cables for a telegraph company. At the same time, he was taking art courses, at the University of London, studies that soon led to his transfer to the telegraph company’s advertising department as a sketch artist and assistant layout man. In 1920 he entered the film industry as a designer of titles for the newly formed London branch of Hollywood’s Famous Players‑Lasky (Paramount). Before long he was the head of the title department, working closely with the screenwriters of the editorial department. Occasionally he was even permitted to direct an unimportant scene that did not involve acting. In 1922 the Famous Players studios, in the borough of Islington, were taken over by a British production company formed by Michael Balcon, and Hitchcock was retained by the new owners as an assistant director; but he soon took on other functions as well, working as an art director and screenwriter on such films as Woman to Woman and The White Shadow (both 1923), The Passionate Adventure (1924), and The Blackguard and The Prude’s Fall (both 1925).

In 1925, Hitchcock was promoted to director, getting as his first assignment a British and German production, The Pleasure Garden. Back in 1922 he had collaborated with actor Seymour Hicks on completing the final scenes of Always Tell Your Wife for an ailing director. In the same year he had also directed a two‑reel fiction film, Number Thirteen, but the production was never completed. The Pleasure Garden was his first real stab at directing, and despite some flaws it proved an impressive debut.

Hitchcock, however, considers his third production, The Lodger (titled in the U.S. The Case of Jonathan Drew; 1927), as his first true film. A suspense drama about a landlady who suspects her new tenant is Jack the Ripper, The Lodger told much of its story in visual terms. It contained some bold special effects and introduced a theme that was to reappear in many of the director’s films that of a man accused of a crime he did not commit, an ordinary man caught in a web of extraordinary events. It was also the first film in which Hitchcock made a personal appearance as an extra, needing one more body to fill the screen. The momentary personal appearance later became a Hitchcock trademark, a career‑long habit initially motivated by superstition and later continued as a gag.

In 1926, Hitchcock married Alma Reville, a film editor and script girl who had been working with him for several years. She would later collaborate as a screenwriter on many of the director’s films. Hitchcock failed to match the commercial success of The Lodger with any of his next few productions, although The Ring (1927), a romantic triangle melodrama with a boxing background, gained the esteem of critics. Hitchcock’s next major production was Blackmail (1929), the British cinema’s first feature film with synchronous sound, although it had been started as a silent film. Blackmail contained some innovations in the use of sound and a number of striking special effects, highlighted by the use of the Schufftan process for the climactic chase sequence through the halls and over the roofs of the British Museum. Similar chases were to highlight many of Hitchcock’s future films.

The director’s next few productions were for the most part unexceptional adaptations of novels and plays, among them Elstree Calling (1930), a musical spoof of Shakespeare’s ‘The Taming of the Shrew’; Juno and the Paycock (1930), a straightforward screen adaptation of the Sean O’Casey play; and Waltzes From Vienna (Strauss’s Great Waltz in the US; 1933), a rickety low‑budget musical. His only truly interesting film of this ebb period was Murder (1930), a slow‑paced but still intriguing whodunit thriller with a backstage background and for that time, daring homosexual motif.

The year 1934 signaled the beginning of Alfred Hitchcock’s international reputation as the master of the thriller genre. During a period spanning five years he turned out a cycle of superb suspense dramas that established him as England’s foremost director. First came The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934), a suspense story about a British couple touring in Switzerland who becomes accidentally involved in international intrigue that culminates in the rescue of their own kidnapped daughter. The film introduced such Hitchcockian hallmarks as the sudden‑shock effect and the lurking of sinister jeopardy beneath a surface of commonplace serenity. A huge commercial success both in England and abroad, The Man Who Knew Too Much was remade by Hitchcock in the US in 1956 as a more elaborate and in many ways more accomplished color production.

The 39 Steps (1935) was an even greater success, both commercially and critically. A free adaptation of a John Buchan novel, it was a delightful combination of hair‑raising suspense and diverting romantic and comic relief that served to heighten rather than diminish the tension. The exciting plot had many implausible twists, and Hitchcock confided in a book‑long interview with Francois Truffaut that in this and future films he was concerned less with plausibility and logical story progression than with building up emotion and mood.

Hitchcock had less success with The Secret Agent (1936), an adaptation of two of Somerset Maugham’s Ashenden stories mixed with material from another source; Sabotage (US title: The Woman Alone; 1937), which, curiously, was adapted from a Joseph Conrad novel titled ‘The Secret Agent’; and the much underrated Young and Innocent (The Girl Was Young in the US; 1937). But these films too were among the finest produced in England in the 30s, providing further evidence of Hitchcock’s maturation as an artist and technician.

Hitchcock capped his so‑called British period with The Lady Vanishes (1938), a superb thriller noted for its technical inventiveness and breezy, often humorous suspenseful action. It won for Hitchcock the best director award from the New York Film Critics. As soon as the picture was completed, Hitchcock was signed by producer David 0. Selznick to direct in America. Before leaving England, he regrettably made a final British film, Jamaica Inn (1939), an unmemorable production that was not at all typical of the style or quality of his work.

Ever since he began directing, Hitchcock had been aware of the technical superiority of American films over the standards prevailing in the British industry during the 20s, and early 30s. He was immensely gratified when Michael Balcon, the producer of The Pleasure Garden, commented after a preview screening: “The surprising thing is that technically it doesn’t look like a Continental picture. It’s more like an American film.” Thus, in 1939, Hitchcock was eagerly looking forward to working with the technical facilities of a Hollywood studio, although by making the move he was clearly risking a career that had just reached a peak of reputation and prestige.

Hitchcock’s first American movie, Rebecca (1940), was not typical of his previous work. It was an adaptation of a Daphne du Maurier romantic novel that he successfully turned into a suspenseful psychological drama. Stylistically, too, the continuity relied more on camera movement than on the more familiar Hitchcockian cutting techniques. Rebecca was a superbly directed production, and it won the best picture Oscar; Hitchcock was nominated for Best Director, but he did not win.