Set in the Civil War in Concord, Massachusetts, the story is dominated by women. Mr. March is fighting in the war, leaving his wife Marmee (Spring Byington) to take care of a household with four daughters. Each of the girls is different from the other. Jo is an ardent tomboy; Beth (Jean Parker) gentle and sweet; Meg (Frances Dee) tender and romantic, and Amy (Joan Bennett) dainty and sly.

In the film’s first part, Cukor presents the special attributes of each sister in brief vignettes. Scolded and punished for caricaturing her teacher, Amy has to stand against the wall with a sign “I’m ashamed of myself.” Jo reads to her aunt; Meg takes care of Mrs. King’s little children; and Beth helps at home.

All four sisters try to live up to their father’s expectations, to be responsible “little women,” to fit into the traditional mold of femininity and domesticity.

All four sisters try to live up to their father’s expectations, to be responsible “little women,” to fit into the traditional mold of femininity and domesticity.

Jo, the most eccentric, is the center of the narrative, and the superlative performance of Katharine Hepburn, singled out at the 1934 Venice Film Festival, makes her all the more noticeable. A tomboy, Jo’s manners and gestures lack femininity, but she is extremely sincere. Early on, she demonstrates her androgynous quality and stretchable personality in a performance of The Witch’s Curse, a play she had written. She switches smoothly from playing the mustached villain to the handsome hero–this in addition to performing all the chores backstage.

Jo is stubborn and at the same time enormously sensitive and vulnerable. In public, she pretends her physical appearance bears no importance. After cutting her long and beautiful hair–to give her mother additional money for her trip–she says, “I don’t care how it looks, my head feels deliciously light and cool, and the hair man said it would soon grow out and it might come in curly.”

Jo is stubborn and at the same time enormously sensitive and vulnerable. In public, she pretends her physical appearance bears no importance. After cutting her long and beautiful hair–to give her mother additional money for her trip–she says, “I don’t care how it looks, my head feels deliciously light and cool, and the hair man said it would soon grow out and it might come in curly.”

In the next scene, however, she is in her room trying to stifle her tears! Jo wants to maintain her family’s unity at all costs; she is against Meg’s relationship with Brooke because it threatens the family’s stability. For her, love is “sickly and sentimental,” and she can’t understand “why is it that things always have to change just when they’re perfect.” Above all, Jo is a proud girl. When Aunt March charges that she is like her father, “waltzing off to war and letting other people look out for his family,” Jo retorts, “There’s nobody looking out for us, and we don’t ask any favors from anybody.”

Jo and Laurie (Douglass Montgomery), the rich boy next-door, fall in love. As children, they share secrets and engage in typically male pursuits, fencing in a duel, because, as Laurie says, “I forget you are a girl.” By the standards of her sisters–and society–Jo uses foul language and reproachable “slang and manners.” But refusing to be “elegant,” she doesn’t care; she likes “strong words that mean something.” Her father’s letter, wishing that his daughters “will fight their bosom enemies and conquer themselves,” so that when he comes back he’ll be “fonder and prouder than ever of my little women,” makes Jo vow “not to be rough and wild.” But to no avail, at the party, she slides off a plate of cake into her lap, messing her dress and the glove she had borrowed from Meg.

The movie conveys effectively the process by which Jo’s restlessness, sorrow, and frustrations, associated with small-town life, are actively channeled into her creative career as a writer (The excitement in selling her first story). Jo declines Laurie’s proposal because she is determined to make her own way as a writer. She goes to New York, to give Laurie a chance to get over his love, where she meets professor Fritz Bhaer (Paul Lukas). The shy European professor introduces her to the sophisticated world of theater and opera, lending her his volume of Shakespeare. “Look at me world, I’m Jo March, and I’m so Happy!” says Jo in a moment of genuine exhilaration. Jo has been writing weekly stories for the “Volcano,” a sensational magazine, but Professor Bhaer advises her to return to something she really understands.

The movie conveys effectively the process by which Jo’s restlessness, sorrow, and frustrations, associated with small-town life, are actively channeled into her creative career as a writer (The excitement in selling her first story). Jo declines Laurie’s proposal because she is determined to make her own way as a writer. She goes to New York, to give Laurie a chance to get over his love, where she meets professor Fritz Bhaer (Paul Lukas). The shy European professor introduces her to the sophisticated world of theater and opera, lending her his volume of Shakespeare. “Look at me world, I’m Jo March, and I’m so Happy!” says Jo in a moment of genuine exhilaration. Jo has been writing weekly stories for the “Volcano,” a sensational magazine, but Professor Bhaer advises her to return to something she really understands.

While the narrative stays most of the time indoors, the film gives some sense of small-town life through its meticulous recreation of Civil War austerity. For instance, the issue of social class is acknowledged. The March family was once rich, but lost its fortune. Amy is humiliated by the kind of school she has to attend, describing the degradation as being thrown with “ill-mannered girls, who stick their noses into refined people’s business.” Poverty, hunger, and infant mortality are also in the background, along with Beth’s illness and death of Scarlet Fever. The four daughters have to sacrifice their luxurious breakfast for a starving family, living in one room with broken windows and no fire.

Little Women” is a moving film about the making of a sensitive writer and the maturation of a small-town girl who transcends her milieu and at the same time retains its heritage.

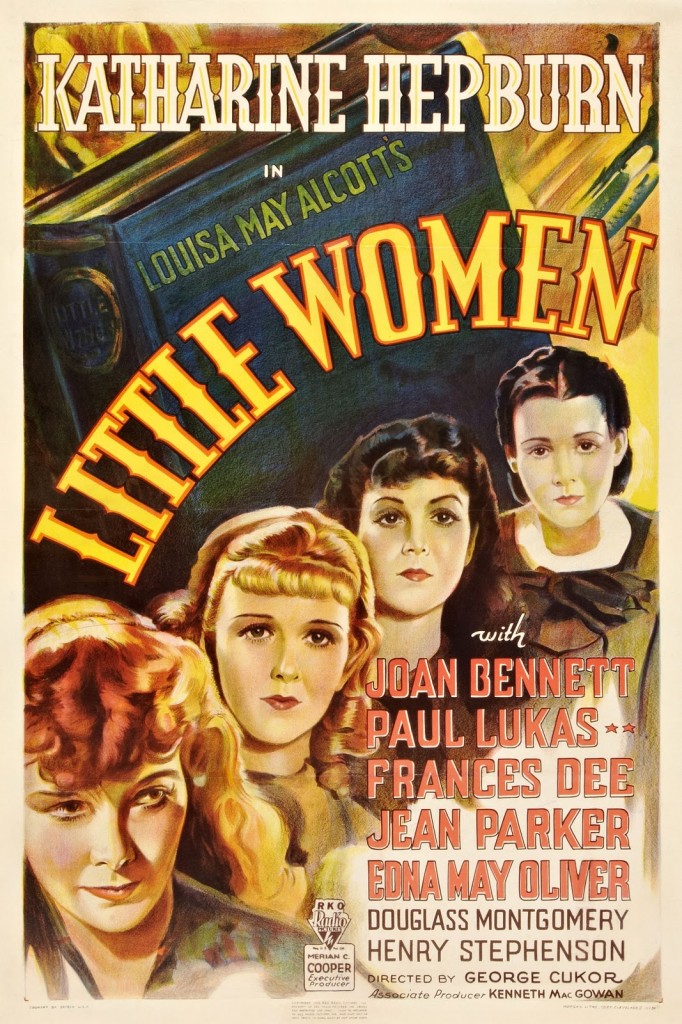

Cast

Katharine Hepburn (26) as Josephine ‘Jo’ March (15 – )

Joan Bennett (23) as Amy March (12 – )

Paul Lukas as Professor Bhaer

Edna May Oliver as Aunt March

Jean Parker (18) as Elizabeth ‘Beth’ March (14 – )

Frances Dee (23) as Margaret ‘Meg’ March (16 – )

Henry Stephenson as Mr. Laurence

Douglass Montgomery as Theodore ‘Laurie/Teddy’ Laurence

John Davis Lodge as Brooke

Spring Byington as Marmee March

Samuel S. Hinds as Mr. March

Nydia Westman as Mamie

Harry Beresford as Doctor Bangs