Directed by Robert Rossen, “Lilith,” Warren Beatty’s third film after his splashy debut in Kazan’s “Splendor in the Grass” and “All Fall Down,” signals the end of the first phase of his career as a misunderstood romantic-rebel youth in the mold of Brando and James Dean.

| Lilith | |

|---|---|

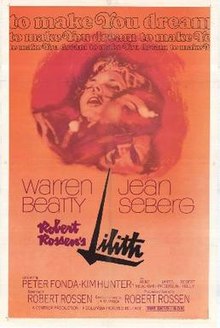

original film poster

|

Our Grade: B (***1/2 out of *****)

Much-misunderstood and under-appreciated at the time of release, “Lilith” is nonetheless an interesting film. After making such social-realist films as “Body and Soul,” “All the King’s Men,” “The Hustler,” all featuring Oscar-caliber performances from their leading men (John Garfield, Broderick Crawford, and Paul Newman, respectively), producer-director Robert Rossen made a French New Wave inspired art film, which differs in style and tone from his previous pictures.

Beatty plays Vincent Bruce, a young war veteran who goes back to Maryland, applies for a job at a mental institute for the affluent and is hired as occupational therapist. Upon meeting Lilith (Jean Seberg), a patient with seemingly angelic face and devilish soul, he falls in love with the disturbed girl and begins an affair with her. Lilith is diagnosed as a nymphomaniac, indiscriminately choosing her sexual partners, including a lesbian.

Lilith wreaks havoc on everyone who falls under her spell, including her lovelorn fellow-inmate Stephen (Peter Fonda, wearing glasses, in atypical role), who is hopelessly enthralled with her, and later on, commits suicide when she rejects him.

Midway, there’s a long, lyrical sequence, in which Vincent and Lilith go to an amusement park, ride horses, and make love in Nature. But even this joyous interlude is rife with tensions, as when Lilith interacts with two boys, erotically caressing one of them.

After Stephen’s death, Lilith slides into sheer madness, and Vincent also begins to feel that his connection to the real world also is tenuous. He first decides to leave the hospital and its unhealthy atmosphere, but madness overtakes him, and he shifts from therapist to patient. In the process, we learn that there’s a history of mental illness in his family. Vincent keeps staring in his room at a photo of his loving mother, who had committed suicide.

The film premiered at the New York Film Festival, after which it began a commercial run that was short and disappointing due to the negative reviews from the mainstream critics who found the film pointless, boring, and irritating. Judith Christ’s account in the New York Herald Tribune was typical: “It’s a muddle of Americana and schizophrenia, sex and sophistry, with a ludicrous plot and enough fuzzy-wuzzy incoherent camera work to turn into an unwilling parody on ‘art or ‘festival’ films at their worst.”

Unfortunately, inevitable comparisons were made with Frank Perry’s “David and Lisa,” co-starring Keir Dullea and Janet Margolin, which deals with similar themes but is simpler and more emotionally accessible, and was released a year earlier. Both “David and Lisa” and “Lilith” were shot in clack-and-white and manifest the influence of European art film (particularly French) on the American cinema of the mid-1960s.

Seen from today’s perspective, one is struck by Eugene Shuftan’s black-and-white photography, which is stunning in nuance and detail, and by the tone and delicacy of treating a difficult subject, even if the filmmaker’s ideas are fuzzy and unclear.

“Lilith” is one of the first American movies to deal with the fine line between sanity and madness, the gray gradations between these two vague states of mind. Admittedly, J.R. Salamanca’s novel had probed these issues more deeply and seriously, but Rossen’s scenario is intelligent and engaging.

The critic Tom Milne has observed astutely that the film’s central argument is that “madness is a two-way mirror, depending on whether you are talking about what it looks like, or what it feels like.”

The very ending of the tale, a close-up of a lost Vincent begging “help me,” after blaming himself for a number of deaths, is disturbing and lingers in memory long after the film is over.

Though still awkward, Jean Seberg (here in long blond hair) shows improvement as an actress after her debut in Otto Preminger’s “St. Joan,” in 1956, and working with the French filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard (“Breathless”). In “Lilith,” she renders a complex characterization of a demented girl, bordering on the witch and the bitch (as Vincent accuses her twice).

The supporting cast, including Jessica Walter, Anne Meacham, Kim Hunter, Gene Hackman and Rene Auberjonois, is also fine.

Ultimately, “Lilith” is more of a remarkable effort than a successful feature, as the critic Milne noted, “to dig a little deeper in an almost untilled field, and to throw some light on that mystery of mysteries, the relationship between madness and the creative imagination.”

Cast

Warren Beatty (Vincent Bruce)

Jean Seberg (Lilith Arthur)

Peter Fonda (Stephen Evshevsky)

Kim Hunter (Bea Brice)

Anne Meacham (Mrs. Yvonne Meaghan)

James Patterson (Dr. Lavrier)

Jessica Walter (Laura)

Gene Hackman (Norman)

Robert Reilly (Bob Clayfield)

Rene Auberjonois (Howie)

Lucy Smith (Vincent’s Grandmother)

Maurice Brenner (Mr. Gordon)

Jeanne Barr (Miss Glassman)

Richard Higgs (Mr. Palskis)

Elizabeth Bader (Girl at Bar)

Alice Spivak (Lonely Girl)

Walter Arnold (Lonely Girl’s Father)

Kathleen Phelan (Lonely Girl’s Mother)

Cecilia Ray (Lilith’s Mother in Dream)

Gunnar Peters (Lilith’s Chauffeur in Dream)

L. Jerome Offutt (Tournament Judge)

Jerome Offutt, Robert Jolivette (Watermelon Boys)

Dina Paisner (Psychodrama Moderator)

Pawnee Sills (Receptionist)

Luther Foulk, Kenneth Fuchs, Steve Dawson, Michael Paras (Doctors)

Credits:

Columbia Picture of a Centaur Production.

Produced, directed by Robert Rossen.

Screenplay: Robert Rossen, based on the novel by J.R. Salamanca.

Camera: Eugen Shuftan.

Editor: Avram Avakian.

Production Designer: Richard Sylbert.

Set Decorator: Gene Callahan.

Music composer: Kenyon Hopkins.

Sound: James Shields, Richard Vorisek.

Sound Editor: Edward Beyer.

Assistant Editors: Barry Malkin, Lynn Ratener.

Costumes: Ruth Morley.

Title Deisnger: Elinor Bunin.

Production Designer: Jim Di Gangi.

The film played at the New York Film Festival, on September 20, 1964.

Running time: 114 minutes.