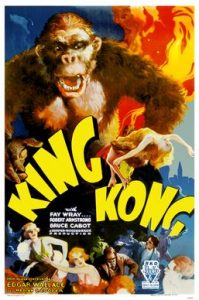

Touted by some as “the Eighth Wonder of the World,” the first King Kong, made in 1933, is considered by some critics–including me–to be the greatest adventure-fantasy-horror movie ever made.

Grade: A (***** out of *****)

Due to changes in the industry, the ownership of “King Kong” has shifted several times after the collapse of the film’s studio, RKO. The movie, which has been shown many times on TV in edited versions (to fit commercial breaks and other considerations), has suffered, and the Warner team is reported to have spent years finding better footage in France and England.

As I pointed out in another piece, “King Kong” came out in one of the worst years of the Great Depression, and thus saved RKO from bankruptcy. A huge box-office hit, it also helped boost the Hollywood industry. Technically, “King Kong” launched a new era of sound and visual effects, with groundbreaking work by stop-motion master Willis O’Brien.

The movie was produced by RKO and co-directed by Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack, and produced by David O. Selznick. Though the notion of high-concept didn’t exist in the 1930s, “King Kong” epitomized it since it was based on a single idea-image that reportedly inspired Cooper to make the movie. As he put it: “Let’s have a beast so large that he could hold the beauty in the palm of his hand, pulling bits of her clothing from her body until she was denuded.” It’s noteworthy, that “King Kong” was one of the last movies made before the Production Code was established as Hollywood’s moralistic guide

The movie was filmed between June 1932 and February 1933 in various locations in California, among them San Pedro, the Bronson Canyon, and, yes, the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles. The set of the scary Skull Island ruins was a leftover from Cecil B. DeMille’s silent epic, “The King of Kings,” used again for the movie “She” (1935). This set went up in a blaze as part of the burning of Atlanta in “Gone With the Wind” (1939), one of the first scenes to be shot.

The running time of the 1933 film is 100 minutes, of the 1976 remake 135 minutes, and of Jackson’s version rumored to be close to three hours! While producer Cooper promised leading lady Fay Wray “the tallest, darkest leading man in Hollywood,” the great ape was really short, only 18 inches, to be exact 95 inches taller than the Oscar statuette!). Kong’s flesh and bone consisted of rabbit fur, which covered molded sponge rubber on an aluminum frame.

In the jungle scenes, the basic scale ratio for its size was one inch to one foot. However, the city scenes required a larger Kong that stood 24 inches tall on the same scale so as not to be dwarfed by the skyscrapers. While Kong was a monkey-size doll, the parts of him that engaged with human actors were built on a massive scale. These included a foot, lower leg, and giant furry paw, a crane like device about 8 feet long, in which Fay Wray writhed sexily and was lifted 10 feet over the studio floor for her big scene atop the Empire State Building.

At the time, state-of-the-art technology was used. The derailed miniature sets were merged and composited with glass paintings, rear-projection backgrounds, stop-motion animation sequences, wooden puppets, and full-size actors. By today’s standards, the film’s special effects look primitive, but “King Kong” was the first film to pioneer the basic machinery and techniques that modern filmmakers, such as Spielberg and Jackson, later refined with the help of electronics and computers.

While there have been many pale imitations, there was only one direct sequel, “Son of Kong” (1933), rushed into production in the wake of the huge success of the first film. Many inferior rip-offs followed in the next decades.

Cast

Ann Darrow (Fay Wray)

Carl Denham (Robert Armstrong)

John Driscoll (Bruce Cabot)

Captain Englehorn (Frank Richer)

Charles Weston (Sam Hardy)

Native Chief (Noble Johnson)

Witch King (Steve Clemente)

Second Mate Briggs (James Flavin)

Charley (Victor Wong)

Socrates (Paul Porcasi)

Crew

Produced and directed by Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack

Screenplay; James Ashmore Creelman, Ruth Rose, based on the story by Cooper and Edgar Wallace

Camera; Eddie Linden, Vernon Walker, J.O. Taylor

Editing: Ted Cheesman

Music: Max Steiner

Art direction: Carroll Clark, Al Herman, Van Nest Polgase

F/X: Willis O’Brien, E.B. Gibson,Marcel Delgado, Fred Reese, Orville Goldner, Carroll L. Sheppird, Mario Larringa, Byron L. Crabbe

Running time: 100 Minutes

King Kong opened at the Radio City Music Hall (6,200-seat) in New York City and the RKO Roxy (3,700 seat) across the street on March 2, 1933. The film was preceded by a stage show, “Jungle Rhythms.” Crowds lined up around the block on opening day, tickets were priced at $.35 to $.75, In its first 4 days, each of its ten-shows-a-day was sold out, setting all-time attendance record. Over the four-day period, the film grossed $89,931.

The film had its official world premiere on March 23, 1933 at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre in Hollywood, with cast and crew in attendance. The ‘big head bust’ was placed in the theater’s forecourt and a 17-act show preceded the film, including “The Dance of the Sacred Ape,” performed by African-American dancers.

The film opened nationwide on April 10, 1933, and worldwide on Easter Day in London, England.

King Kong was re-released in 1938, 1942, 1946, 1952 and 1956, after a successful telecast on WOR-TV.

Commercial Appeal

The film was a box-office success making about $5 million in worldwide rentals on its initial release, with an opening weekend estimated at $90,000.

However, receipts fell by up to 50% in the second week of release because of the national “bank holiday” called in President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s first days in office.

During the film’s first run it made a profit of $650,000.

Prior to the 1952 re-release, the film had worldwide rentals of $2,847,000 including $1,070,000 from the U.S. and Canada and profits of $1,310,000.

After the 1952 re-release, the film made additional $1.6 million in the U.S. and Canada, taking its total to $3.9 million in cumulative domestic. Profits from the 1952 rerelease were estimated at $2.5 million