Set during the Depression era, Kansas City contrasts the two opposite poles of the social hierarchy, while criticizing the American political system and the impact of pop culture on innocent people.

Grade: C+ (** out of *****)

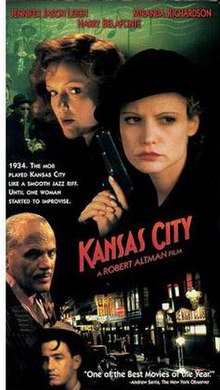

Unfortunately, Robert Altman deals with these serious issues in a reductive way, by centering on the relationship between two rather uninteresting white females, played by Jennifer Jason Leigh and Miranda Richardson.

Like in other Altman films, the context and background, here the glorious days of black jazz that flourished in his hometown, are more interesting than the central narrative, but, alas, the music is just a distraction and there is not much of it.

In Altman’s oeuvre, “Kansas City” will have to be considered a minor, unsuccessful film, at least when judged against major works like the Western “McCabe and Mrs. Miller,” “The Long Goodbye,” the Hollywood satire “The Player,” and the anthology “Short Cuts.” It’s certainly a lesser work than his 1974 Depression-era chronicle, “Thieves Like Us.”

In Cannes Film Fest, where the movie premiered in competition, Altman described “Kansas City” as a personal work, though he was only nine in 1934 when the action is set. Even so, the film is inspired by his memories (or fantasies) of the “18th and Vine” district, which was then a Mecca for black musicians.

The saga boils down to the impact of bad, desperate times, and how they drove various individuals to extreme behavior, manifest in senseless, normless, and criminal activities

The opening scene shows a working-class woman invading into a rich, elegant home, threatening the privileged bewildered lady with a gun and then forcing her to take drugs. The interloper, who bears the clich name of Blondie O’Hara (Jennifer Jason Leigh as a femme who thinks of herself as Jean Harlow,), has schemed the kidnapping of Carolyn Stilton (Miranda Richardson), the socialite wife of Democratic Party politician Henry Stilton (Michael Murphy), Roosevelt advisor,

hoping that it will get her back her hoodlum husband Johnny O’Hara (Dermot Mulroney), who’s mysteriously disappeared.

Not brighter than Blonde, Johnny has pulled a dim robbery of a big black gambler (while wearing blackface), a crime for which he is apprehended by Hey-Hey Club owner and the underworld kingpin Seldom Seen (a terrific Harry Belafonte), who tortures O’Hara during performances of Lester Young and Coleman Hawkings.

A Kansas City native, Blondie drags the laudanum-addicted Carolyn with her in her search of Johnnie. For her part, Carolyn is forced to drag her own husband, a top FDR adviser, into the sordid scheme, set against the 1934 national election day.

Meanwhile, a ruthless mob thug (Steve Buscemi, well cast) rounds up derelicts, drunks, and unemployed and sends them out to vote the Party line. His reaction to any interference or interruption with his action is nothing short of shockingly murderous.

Script by Altman and Frank Barhydt (who co-penned “Short Cuts”) is episodic, busy but superfluous, even though the saga spans only a day or so. The disorienting, diffuse yarn accounts for the fact that we never get to know either woman. And it doesn’t help that they are types. Blondie is hard and brittle, whereas Carolyn is soft and unfocused. Blondie holds the upper hand due to her gun and task, but the power balance and psychological dynamics begin to shift.

But there’s always the grand music to fall on: A big band filled with the best contemporary jazz musicians, from Cyrus Chesnut to David Murray, even if Altman cuts away from them once they (and we) begin to get excited.

As noted, there’s nothing particularly interesting about either character. The notion that the lowlife woman should bond and trade souls with the rich, pretentious lady is preposterous. Moreover, there is no chemistry between the two females, or congruity between their acting styles, just false tension. Of the two, Leigh gives the more mannered performance, though the usually brilliant Richardson seems unable to find anything significant to say or to do.

In contrast, Belafonte, who seldom makes movies anymore, is startling to watch as the nasty, pragmatic killer, but unlike the femmes, he gets meager screen time.

Altman’s penchant for documentary style conflicts with the absurd narrative. Strangely, he is not warm or nostalgic at the prospect of the past, and he just goes back and forth between personal grievance and larger political forces, though the two domains remain separate.

Cast against type, Harry Belafonte shines as the at once charismatic and menacing Seldom Seen, even when asked by Altman to deliver largely inconsequential about this and that.

Ultimately, despite the honorable intent to explore Depression-era problems of Prohibition, Democratic Party machine politics, racial segregation, and jazz clubs, “Kansas City” comes across as portentous and superficial.

As always, the periphery, the jazz world and its black musicians of 1930s Kansas City, is mmore interesting than the center of the rambling narrative. The tale moves freely but arbitrarily among its idiosyncratic characters in an effort to present a film parallel to the improvisational nature of 1930s jazz. Indeed, many of the film’s most important sequences take place in Seldom Seen’s club, with contemporary jazz performers.

Credits:

MPAA: R

Running time: 115 Minutes.

Directed By: Robert Altman

Written By: Robert Altman and Frank Barhydt

Cinematography: Oliver Stapleton

Edited by Geraldine Peroni

Production company: Ciby 2000

Distributed by Fine Line Features

Release date: August 16, 1996

Running time: 116 min

Budget: $19 million

Box office: $1,356,329

Cast

Jennifer Jason Leigh as Blondie O’Hara

Miranda Richardson as Carolyn Stilton

Harry Belafonte as Seldom Seen

Michael Murphy as Henry Stilton

Dermot Mulroney as Johnny O’Hara

Steve Buscemi as Johnny Flynn