Next to John Ford, Howard Hawks was the other director who had greatly influenced John Wayne’s career.

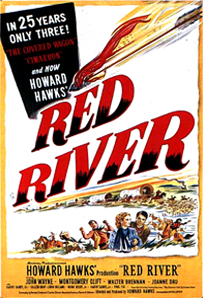

Wayne had appeared in five films directed by Hawks, four of which were Westerns: the classic epic Red River, and three that are considered a Western trilogy because they share similar plots and themes, Rio Bravo, El Dorado, and Rio Lobo.

The fifth collaboration, Hatari! an adventure filmed in Africa, deals with an international team of animal hunters, headed by Wayne.

What marked the Wayne collaboration with Hawks, as compared with that with Ford, is its greater mutual dependency, possibly because Wayne was becoming an accomplished actor by the time Hawks decided to cast him as the lead in Red River.

Red River: Turning Point in Wayne’s Career

It was Hawks who approached Wayne with the idea of Red River, his first foray into the Western genre. “You’re gonna be an old man pretty soon,” he told Wayne, “and you ought to get used to it.” “You better start play characters,” Hawks advised, “instead of that junk you’ve been playing.”

Hawks was also the first director to give the actor real freedom in interpreting his juicy role of Thoman Dunson. Never beyond learning, Wayne was given useful advice, “do three scenes (memorable acting bits) in a picture and don’t annoy the audience in the rest.” Indeed, Hawks believed that it was enough for performers to excel in a few scenes, granted they did not irritate the audience in the others.

Hawks was also the first director to give the actor real freedom in interpreting his juicy role of Thoman Dunson. Never beyond learning, Wayne was given useful advice, “do three scenes (memorable acting bits) in a picture and don’t annoy the audience in the rest.” Indeed, Hawks believed that it was enough for performers to excel in a few scenes, granted they did not irritate the audience in the others.

Hawks thought that Red River “made Wayne a good actor, because he does not try hard to do things he’s not capable of doing.” He was “a hell of a lot better than most people think he is,” said Hawks, and he had “more power than any other man on the screen.” “The only problem with Wayne,” the director felt, “is who do you get to play with him,” because “if you get somebody who’s not pretty strong, he blows them right off the screen. He doesn’t do it purposely–that’s just what happens.”

Initially, Wayne had some reservations about Montgomery Clift because he was a stage actor, with no screen experience, and a proponent of New York’s Method acting, which Wayne and other Hollywood actors disliked. “Howard (you) think we can get anything going between that kid and myself” he asked the director after his first meeting with Clift, to which Hawks said, “I think you can.”

After a few scenes, Wayne had to conced, “You’re right. He can hold his own, anyway, but I don’t think we can make a fight.” Hawks then told the star, “Duke, if you fall down and I kick you in the jaw, that could be quite a fight. Don’t you think so” Wayne reportedly said, “Okay,” and that was all there was to it. But it took several days to make Clift “tough enough to be against Wayne because he didn’t know how to punch or move when we rehearsed.”

Clift himself was puzzled by the idea of fighting with and punching Wayne. He reportedly disliked the brawling scene because he thought that the showdown with Wayne, a giant of a man, feel like a farce; Clift was short and slender.

But many critics singled out the casting of Clift opposite Wayne. “The greatest triumph,” wrote one reviewer, “was creating the illusion of a hidden force of character capable of holding his own with Wayne, who is at least twice his size.”

Clift was apparently disturbed by Wayne’s acting style. Wayne’s technique was not to act for the camera, but to react to the situation called by the script as naturally as possible. Clift, by contrast, was used to stage work, to getting to know his fellow actors and relating to them emotionally. He complained to Hawks that Wayne did not look at him when they were in the same scene. But under Hawks’ direction, they adapted to each other, with each playing off the other’s differences, in appearance, voice, and manner, so that both ended up giving distinguished performances. Red River turned out to be an important experience for all participants, convincing Hawks to use Wayne in another Western, Rio Bravo, which also became a box-office hit.

Hatari!

Of their third film together Hatari! Wayne said, “I think it’s a good story and Hawks and I have had great success together, so I have confidence in him.”

For his part, Hawks described the special relationship he had with Wayne in the following way: “The last picture we made (Rio Lobo), I called him up and said, ‘Duke, I’ve got a story.’ He said, ‘I can’t make it for a year, I’m all tied up.’ And I said, ‘Well, that’s all right, it’ll take me a year to get it finished.’ He said, ‘Good, I’ll be ready.’

When he came down on location, he said, ‘What’s this about’ And I told him the story. He never even read it. He didn’t know anything about it.”

Wayne later confirmed this story: “I just have to ask Howard (Hawks) which hat he wants me to wear and which door I come in.”

But this implicit, almost-blind, faith in Hawks had its price: many critics felt that Wayne’s talent was misused in Rio Lobo, their last collaboration and a much weaker Western than either Rio Bravo or El Dorado.

Significantly, Hawks himself attributed its failure to the casting, “I didn’t like it. I didn’t think it was any good. I only made it because I had a damn good story and the studio couldn’t afford to put a man as good as Wayne in it, so we ended up with the cast we had.”

Rio Lobo’s cast, one of the weakest in a Wayne movie, included such unknown or inexperienced actors in leading parts as Jorge Rivero, Jack Elm, and Chris Mitchum (Robert’s son).

Hawks directed Westerns and action movies with other actors, such as The Big Sky, starring Kirk Douglas, but they were pale features, compared with those starring Wayne. “If you try to make a Western with somebody besides the Duke,” he observed, “you’re not in the sphere of violence and action that you are when you’ve got Wayne.”

Of the actor’s greatest assets, Hawks singled out his “force” and “power,” and the fact that “he thinks quickly and thinks right.”

Wayne was considered by Hawks to be the very best: “When you have someone as good as Duke around, it becomes awfully easy to do good scenes because he helps and inspires everyone around him.”

Curiously, Lee Marvin did not think so; when he asked Hawks to direct him in Monte Walsh, he told him he wanted it to be a Lee Marvin Western, not a John Wayne one. Hawks is reported to have answered with a good deal of sarcasm, that Marvin need have no worry about being as good as Wayne–and he did not direct the film!

The relationship with Hawks, like that with Ford, extended beyond making pictures. Hawks gave the actor, as a token of appreciation for his work in Red River, a silver belt buckle shaped into the design of the “Red River D.”

And another pleasant surprise greeted Wayne when he returned to the set of Rio Lobo after winning his Best Actor Oscar Award. Under Hawks’ initiative, all the actors and crew members wore eye patches, a tribute to Wayne’s one-eyed marshal in True Grit. The Academy Award apparently confirmed what Hawks had known all along, “John Wayne has just come to be recognized for the good actor he is.” “I’ve always thought he was a good actor,” Hawks explained, “I always thought he could do things that other people can’t do.”

Rio Lobo, in 1970. turned out to be Hawks’ last picture. Although highly respected by French film critics, Hawks was underestimated in his own country until the late 1960s, when a new generation of critics re-examined his work.

Hawks was awarded an Honorary Oscar in 1974 for his cumulative work of four decades, which was interpreted as a compensation for never winning a legitimate, competitive directorial Oscar. Hawks had been nominated for the Best Director Oscar just once, in 1941, for the bio-picture Sergeant York, starring Gary Cooper, which is one of his more conventional pictures.

Hawks died at his home in 1977.