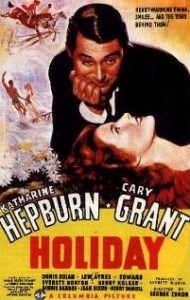

When Holiday was produced on Broadway in 1928, Hope Williams played the role of Linda Seton. Her understudy was Katharine Hepburn, then an unknown and inexperienced actress.

For two years, she marked time offstage, but her chance to perform never materialized. Ironically, Hepburn decided to use a scene from this play in her screen test for Bill of Divorcement (which Cukor directed).

Cukor’s version was the second adaptation of Barry’s play, first done as a film in 1930, offering Ann Harding one of her best, Oscar-nominated roles.

The 1930 picture was also nominated for its adapted screenplay, by Horace Jackson, but it didn’t win; the writing Oscar went to Hoard Estabrook for Cimarron, which also received the Best Picture Oscar.

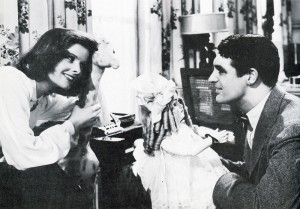

Once again, Hepburn was perfectly cast in a role that seemed tailor- made to her specific qualities. Linda Seton, a rebellious society girl from Park Avenue, falls in love with her sister’s fianc, Johnny Case (Cary Grant), a boy from the slums with a knack for making money–amd enchanting peole with hs charm and atheletics.

Once again, Hepburn was perfectly cast in a role that seemed tailor- made to her specific qualities. Linda Seton, a rebellious society girl from Park Avenue, falls in love with her sister’s fianc, Johnny Case (Cary Grant), a boy from the slums with a knack for making money–amd enchanting peole with hs charm and atheletics.

When Johnny decides to take a holiday in order to explore the world, Julia (Doris Nolan) is horrified, but he finds a kindred spirit in Linda. “I’ve got all the faith in the world in Johnny,” Linda proudly declares, “Whatever he does is all right with me. If he wants to sit on his tail, he can sit on his tail. If he wants to come back and sell peanuts, how I’ll believe in those peanuts!”

Hepburn delivered her lines with conviction, eloquence, and commanding authority. Linda, in fact, would become an archetypal Hepburn heroine: a tomboy rebel of a woman, endowed with extraordinary intelligence and individuality.

One of Hepburn’s most accomplished characterizations, the role touched all of the aspects of her complex personality, her toughness as well as vulnerability.

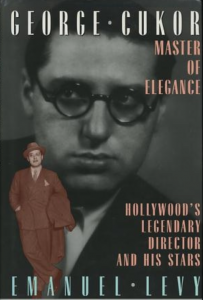

Cukor held that, to be emotionally effective, Barry’s work required a particular kind of acting, lightly stylized but not too affected. Barry’s witty dialogue seemed realistic, but it was not; the words had a distinctive rhythm all their own. Hepburn understood Barry’s lyric quality, accentuating the rhythm of his lines with a kind of “singsong” voice. It was a technique Hepburn would refine to perfection in The Philadelphia Story, (which some critics, including me, considered to be her most flly realied perfomance)

Donald Ogden Stewart and Sidney Buchman’s brilliant script tried to be faithful to the play, grounding its story almost entirely with dialogue–most of it Barry’s own. Then, to update and enrich the story, Stewart introduced some satirical allusions.

Like all good comedies,Barry’s could be played seriously as well. Cukor relished at taking a serious subject and treating it with “impertinence and gaiety.” His fluent adaptation actually improved on the play, creating a new genre: comedy-drama,or dramedy. Cukor held that true comedies spring from painful realities, and that without the tragic underlayer, the comedy becomes trivialized.

“I believe in the detached approach for comedy,” he told critic Lambert, “If you really look at anything, there’s always a comic note, and a painful note too. One brings the other to life.”

Cukor also understood that directing a screen comedy was different from doing a stage one: “On stage, you can play for laughs and wait for them, but on the screen, you have to get the laughs without playing for them.”

Cukor also understood that directing a screen comedy was different from doing a stage one: “On stage, you can play for laughs and wait for them, but on the screen, you have to get the laughs without playing for them.”

Both Barry and Cukor were artists who excelled in creating nuance. Barry was a subtle writer, and full of surprises. In his plays, the characters are rarely what they seem to be; each reacts in unexpected ways, underlying the the issue of the inevitable differences between appearance and reality.

for example, the surface closeness (and politeness) of the two sisters actually hides mutual dislike, which, initially neither of them is aware of. And when Julia realizes that Johnny is going to walk out on her, she’s not crushed, but, in fact, relieved. Cukor handled these transitions with tremendous ease and delicacy, giving the film a fresh and endearing quality.

When the play was originally written, the stock market was booming, and wealth and prosperity were in abundance. Barry’s view of the rich was that of an outsider; they were seen through Johnny’s eyes. For Barry, there was nothing ostentatious about the wealthy people’s way of life. Even when owned grand houses and limosines, but they didn’t flaunt them in public; everything was understated.

In the cintext of the late Depression, it was bold and interesting for Cukor to present a young man who wanted to enjoy life, instead of just conforming to mainstream nrms. Johnny is initially patronizing toward Linda, before finally realizing tha she is the right one for him.

In his second film with Cukor, Cary Grant gave nothing short of a dazzling performance. In his knockout scene, which he did in perfect English and with restraint, Grant tells the rich where to go, while dashing off with a disdain of conventionality. Grant’s smooth performance later made him one of Hollywood’s most popular leading men, especially in comedies.

Holiday completed shooting on April 20, and opened in New York, at Radio City Music Hall, on June 15.

At Oscar time, Cukor was disappointed that the movie received only one nomination, for Stephen Goosson and Lionel Banks’s Interior Decoration; the winner was Carl J. Weyl for Errol Flynn’s swashbuckling adventure, “The Adventures of Robin Hood.”

Despite favorable critical reaction, the film failed with Depression audiences, for whom selling peanuts was a reality, not a joke. Linda, the little rich girl, who stays in her childhood nursery and denounces the filthy rich, was more appropriate for audiences of earlier times. Nonetheless, it was personally gratifying for Cukor that Barry regarded this movie version as “a brilliant and beautiful piece of work.”

Cukor on working with Hepburn and Cary Grant

During the extended preparations of the script and casting of Gone With the Wind (GWTW), which took three years, George Cukor was assigned to direct Philip Barry’s Broadway play, Holiday, at Columbia. Selznick hoped that by the time Cukor finished Holiday, they would have a wonderful script. Holiday was a pleasant distraction from the frantic activities of GWTW. It was fun to work on a picture that had a definite shooting schedule–with a beginning, middle, and end.

When Holiday was produced on Broadway in l928, Hope Williams played the role of Linda Seton. Her understudy was Hepburn, then an unknown and inexperienced actress. For two years, she marked time offstage, but her chance to perform never materialized. Ironically, Hepburn used a scene from this play in her screen test for Bill of Divorcement.

When Hepburn learned that Columbia had acquired the rights to Holiday, she began a personal campaign to win the role, as her film career at this point was in trouble. After Bringing Up Baby, an artistic success but commercial failure, Harry Brandt, president of the Independent Theater Owners Association of America, published a list of stars who were “box office poison.” Hepburn headed a roster, which included other “Cukor girls,” Garbo and Kay Francis. Brandt’s slur, published in a trade paper, was picked up by the national press and received a lot of publicity. It also caused considerable damage to the status of these stars at their studios.

But Columbia was a relatively small studio, and Hepburn had little difficulty in persuading its boss, Harry Cohn, to cast her as Linda Seton. She also persuaded Cohn to borrow Cukor as director and cast Cary Grant as co-star. In fact, in advertising the film, vice-president Jack Cohn used the “box-office poison” label as a selling point. “Is it true what they say about Hepburn” he provocatively asked in a public message, feeling sure this time he had the makings of high quality and commercially viable film.

Like all good comedies, Barry’s could be played seriously as well. Cukor relished at taking a serious subject and treating it with “impertinence and gaiety.” His fluent adaptation actually improved on the play, creating a new genre: comedy-drama. Cukor held that true comedies spring from painful realities. Without the tragic underlayer, the comedy becomes trivialized. “I believe in the detached approach for comedy,” he told Lambert, “If you really look at anything, there’s always a comic note, and a painful note too. One brings the other to life.”

Cukor also understood that directing a screen comedy was different from a stage one: “On stage, you can play for laughs and wait for them, but on the screen, you have to get the laughs without playing for them.”

When the play was originally written, the stock market was booming, and wealth and prosperity were in abundance. Barry’s view of the rich was that of an outsider; they were seen through Johnny’s eyes. For Barry, there was nothing ostentatious about the wealthy people’s way of life. They owned grand houses, but they didn’t flaunt them; everything was understated.

Holiday completed shooting on April 20, 1938 and opened in New York, at Radio City Music Hall, on June 15 of that year.

Despite favorable critical reaction, the film failed to attract Depression audiences, for whom selling peanuts was a reality, not a joke. Linda, the little rich girl, who stays in her childhood nursery and denounces the filthy rich, was more appropriate for audiences of earlier times. Nonetheless, it was personally gratifying for Cukor that Barry regarded his movie version as “a brilliant and beautiful piece of work.”

Oscar Nominations: 1

Interior Decoration: Stephen Gooson and Lionel Banks

Oscar Awards: None

Oscar Context:

The Interior Design Oscar went to Carl J. Weyl for Errol Flynn’s The Adventures of Robin Hood.