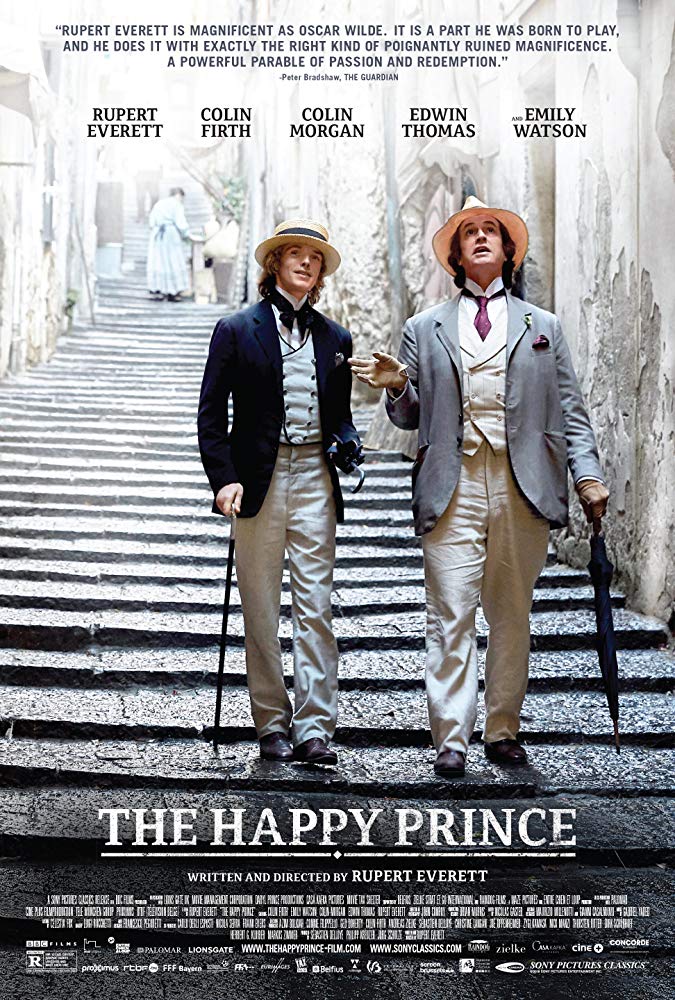

In The Happy Prince, Rupert Everett depicts the last years of Oscar Wilde, after his prison term for “gross indecency” made him a social pariah.

A passion project, The Happy Prince is nearly a one-man show–it’s written, directed, and starring the Everett.

Most of the tale, which is grim and dreary, centers on famed writer Oscar Wilde’s final three years, his social isolation, his health issues, his increasing despondence, and above all public humiliation.

The tale begins in London, circa 1890, with Wilde as a poor and destitute man, all alone in London streets, having to beg for money from one of his former female patrons and fans.

At the prime of his success, circa 1885, Oscar Wilde wrote to his friend James Whistler, “Be warned in time, James; and remain, as I do, incomprehensible: to be great is to be misunderstood.” Wilde could not have known then how prophetically true those words would be a decade later.

After his highly publicized trial in 1895, Wilde was convicted of “gross indecency” and sentenced to two years of hard labor. Most of his friends deserted him.

Upon his release in 1897, his health in severe decline, he went into exile to France and died three years later, at the young age of 46.

Exiled, he is living in Parisian squalor in a world far away from the London’s literary and art contexts, in which he had reigned supreme for decades

The movie, which is well-intentioned and impressively mounted in the technical departments, is structurally shapeless, and technically flawed.

Everett’s debut is sharply uneven. As director, he might have dwelled too much on the suffering, martyrdom, and self-pitying episodes, instead of presenting a more balanced portraiture. And there may be too much narration (by Everett), in lieu of dramatic presentation.

At times, the film feels like first feature, as when the camera is in the wrong place, or when the editing makes the material more fragmented and fractured than it must be.

Some of the flashbacks, as those depicting his childhood and close relationship to his mother (played by Emily Watson), are too brief and seem arbitrary in the order in which they are presented.

That said, it is a personal film that chronicles a tragic chapter, about which some of us know from reading literary history but we have not seen it shown with such detail on the big screen. You could say that Everett (an openly gay actor) was a natural choice for playing a homosexual character in a punitive and restrictive socio-political milieu.

Everett is particularly powerful in the tale’s last reel, when he portrays the disgraced and dying Wilde, a man personally wounded and creatively damaged by a vicious abuse, yet somehow managing to maintain his sense of dignity and inner self.

An auteurist effort that would not have existed without Everett’s passionate involvement, The Happy Prince is worth seeing as a document of a crucial era, whose dominant ideology unfortunately still bears relevance today.

End Note:

Wilde was pardoned, along with 50,000 other men, over a century later, as late as 2017.