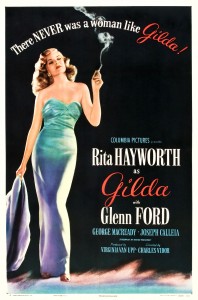

Viewed from a contemporary or modernist perspective, Charles Vidor’s Gilda, made in 1946, is a significant erotic film, and a classic film noir. Among many merits, it boasts spectacular performances from Rita Hayworth and Glenn Ford, showing the stars at their most glamorous and seductive.

The original story of Charles Vidor’s Gilda was specifically written by Virginia Van Upp, who was assigned by Columbia’s top honcho, Harry Cohn, to create a vehicle for his favorite star, and also to oversee the production.

Our Grade: A- (**** 1/2 out of *****)

The film deals with many taboo issues, both implicitly and explicitly, prime among which is repressed sexuality.

In many ways, the movie has gained its fame, cult status, and notoriety, due to its erotic and sexual entertainment values, dwelling on the themes of yearning, desire, and the desire to desire.

As a result, this feature has often been called “perverse,” what with its touches of sadomasochism and a byzantine-like plot, which spirals in many directions and is never predictable. Gilda in fact revealed sexual repression and perversion (by standards of the time) of various sorts. At the time of its release, Gilda increased awareness in its viewers (male and viewers) of sexual mores and codes and practices that had been previously unheard of.

In particular, Hayworth’s portrayal of Gilda as a sexually aggressive, dangerous, vampire-like female offered a new twist on the more conventional Hollywood mode of the ways women heroines were presented. The New York Times conservative critic Bosley Crowther dismissed the film and its star as being “crude.”

Furthermore, the two male leads, played by Glenn Ford and George Macready, have an extremely close relationship–an intimate bond–manifest in their words, gestures. and the way they look at each other, which today appears to be nothing short of latently homosexual.

Furthermore, the two male leads, played by Glenn Ford and George Macready, have an extremely close relationship–an intimate bond–manifest in their words, gestures. and the way they look at each other, which today appears to be nothing short of latently homosexual.

Consider the first exchange of words between the older businessman Ballin and the younger pretty boy Johnny Farrell, whom he rescues late one night, while cruising the streets.

Later on, when Ballin describes his cane, which he points at Johnny, he might as well be talking about his penis.

Ballin: It is a faithful and obedient friend, it is silent when I wish to be silent, it talks when I wish to talk.

Johnny: That’s your idea of a friend?

B: That is my idea of a friend.

J: You must lead a gay life.

B: I lead a life I’d like to lead

The use of the word gay is particularly interesting, as in the 1940s it did not denote homosexual man or homosexual lifestyle; it entered our popular vernacular in the 1960s.

Throughout the plot, especially in its first part, Johnny is described as “a boy,” a nickname used by many men in the gay sub-culture, when referring to the distinction between “a real man” and “a boy,” usually a younger sexy male (an object of desire), often engaged in a relationship with older, more masculine men (the expression of “daddy’s boy” is also relevant here).

Later on, at the casino, Ballin, accompanied by his wife Gilda and Johnny, proposes a toast for “the three of us.” When Gilda asks who’s the third friend, “is it a him or a her,” Johnny says, “it’s a her, because it looks like one thing and then right in front of your eyes, it becomes another thing.”

We wonder, what exactly is he talking about? Is he a misogynist who’s describing the ever-shifting, unreliable nature of women such as Gilda? Could it be that Johnny (subconsciously) implies that Ballin’s friend is like a penis, an organ that’s usually loose and flaccid form, but under excitement while getting an injection of blood, the penis changes forms by getting bigger, sharper, and erect?

These aspects of the film introduced viewers to new sexual worlds, in a stylish mode, and later on, an element of camp was added by more sophisticated viewers who were reading between the lines. In other words, what for some audiences is the film’s real subtext (potentially there to be unveiled), for others it might be more explicit, on the textual level itself.

The young Glenn Ford was not only very attractive but also had a boyish voice. In Gilda, he is referred to as a “pretty” (not handsome) boy; pretty is usually used to describe girls and women not boys or men.

Consider the scene in which Johnny’s striped gown is contrasted with Mundson’s long black robe. “How pretty you look in your night gown,” Gilda comments, unmanning Johnny for the second time as “pretty.”

Gilda is also significant, because the film presented a new, more liberated sexual world, which existed amid the more pervasive sexual repression and bourgeois domesticity of the 1940s. The movie was made just after WWII, in a year in which the film that swept all the Oscar Awards was William Wyler’s The Best Years of Our Lives.

Subsequently, Rita Hayworth became the decade’s greatest pin-up girl, perhaps the first real one to follow Jean Harlow, a sex symbol in the 1930s, who died very young. Hayworth would be replaced as a sex goddess by the blond and voluptuous Marilyn Monroe. Of all three femmes, I thing Hayworth is the most interesting, partly because of her being a symbol of the dichotomy between sexual imagination and sexual realities.

When the U.S. Air Force sought a name for the Bikini atomic bomb, they appropriately chose “Gilda.” The analogy between an atomic bomb and a dangerous female was clearly made by the Air Force in this way. The name “Gilda” came to signify a wild woman. Also, as the film was in many ways a played off of Casablanca’s sexually repressed plot, it was as if Gilda uncovered and revealed the full sexual implications of that earlier beloved film (1942). Rita Hayworth’s sexy performance also revealed the true nature of Ingrid Bergman’s role in Casablanca.

When the U.S. Air Force sought a name for the Bikini atomic bomb, they appropriately chose “Gilda.” The analogy between an atomic bomb and a dangerous female was clearly made by the Air Force in this way. The name “Gilda” came to signify a wild woman. Also, as the film was in many ways a played off of Casablanca’s sexually repressed plot, it was as if Gilda uncovered and revealed the full sexual implications of that earlier beloved film (1942). Rita Hayworth’s sexy performance also revealed the true nature of Ingrid Bergman’s role in Casablanca.

Through Hayworth’s performance, many female viewers were made aware of their inherent rights as women, long before the feminist implications which prevail in the 1991 female buddy movie, Thelma and Louise, starring Susan Sarandon and Geena Davis.

One way Gilda achieved this effect was through the songs “Amada Mio” and “Put the Blame on Mame,” which Hayworth “sang” (she was actually dubbed) in the film. “Put the Blame on Mame” became especially popular. The lyrics of this song are about a woman much like Gilda, a woman who has been used and abused by men but comes to the realization that she does not have to put up with it anymore. The expression, in song lyrics, of Gilda’s determination to stand up against male repression, might have had an even much greater impact than the film’s dialogue.

Gilda also contributed to the creation of camp culture. The movie might have been misunderstood upon its release because it was the first full-fledged camp film. Of course, campiness and self-reflection have since become widely accepted by Hollywood. For instance, no one would be shocked by a parody of Casablanca in this day and age. However, audiences in 1946 were uncertain about what Gilda was all about. Gilda set in motion an important part of popular culture that we take for granted now: on screen campiness. Just count the number of times that both Johnny and Gilda say how much they hate each other. Hate for the other, of course, conceals self-hatred, self-contempt, and self-degradation.

The film ends with Gilda’s sexual reformation, and dismissal of the homoerotic inferences in the earlier relationship between Johnny and Ballin. As the film was released in 1946 soon after World War II had ended and just as the Cold War was gaining momentum, it was important that Hollywood portray Americans as “normal” people, and Gilda’s independence had to be domesticated. However, the film’s sudden “happy ending” could not utterly obscure the sexual issues that the film had raised earlier in the narrative.

The film ends with Gilda’s sexual reformation, and dismissal of the homoerotic inferences in the earlier relationship between Johnny and Ballin. As the film was released in 1946 soon after World War II had ended and just as the Cold War was gaining momentum, it was important that Hollywood portray Americans as “normal” people, and Gilda’s independence had to be domesticated. However, the film’s sudden “happy ending” could not utterly obscure the sexual issues that the film had raised earlier in the narrative.

At the time, Gilda both defined and reflected the prevalent type of woman in film noir, the “femme fatale,” alluring, dangerous and destructive. Director Charles Vidor seems to have capitalized on the sadomasochistic angles of the genre. In the course of the film, Johnny exerts a series of punishments on Gilda, forbidding her to dance with other men, smacking and slapping her, treating her as “a piece of dirty laundry” that needs to be picked up and then dropped. Later on, Johnny weds Gilda just in order to possess her emotionally and mentally and isolate her physically (locking her up in a sexless bond), forcing her into exile, making her beg on her knees to let her go, let her regain her freedom. To be sure, in punishing Gilda, Johnny begins as a sadomasochist who ultimately ends up as a masochist, the very victim of his behavior.

In one of the film’s most powerful scenes, Johnny begs Gilda to forgive him, “I’ve been wrong, take me back.” The film goes out of its way to reclaim the prodigal son in order to appeal to mainstream audiences.

The voyeuristic elements are prevalent throughout the tale, as when Gilda asks for help to unzip her tight dress, claiming “I’ve never been good with zippers.” And they are most obvious in the striptease scene that Hayworth performs in a sleazy nightclub, mostly populated by older predatory men. She is wearing a notoriously revealing strapless black satin evening gown, along with matching elbow-length black gloves, which she slowly takes off and throws at the cheering audience. Costume designer Jean Louis later said that Hayworth’s gown in Gilda was “the most famous dress I ever made.”

The shooting process was troubled due to various reasons, such as casting Glenn Ford late in the game. There were also disagreements over the specific places in the story in which to insert choreographer Cole’s seductive dances. Cole claimed that the inspiration for his lavish dances for Rita Hayworth derived from first-hand knowledge of famous strippers in Hollywood.

Hayworth, the reigning queen of Columbia, became Hollywood’s most popular sex goddess of the 1940s and early 1950s. Curiously, when Hayworth experienced marital problems with Aly Khan, she blamed Van Upp, claiming: “It’s all your fault. You wrote Gilda, and every man I’ve known has fallen in love with Gilda and waken with me!”

Cast

Rita Hayworth as Gilda Mundson Farrell

Glenn Ford as Johnny Farrell

George Macready as Ballin Mundson

Joseph Calleia as Det. Maurice Obregon

Steven Geray as Uncle Pio

Joe Sawyer as Casey

Gerald Mohr as Capt. Delgado

Mark Roberts as Gabe Evans

Ludwig Donath as German

Don Douglas as Thomas Langford

Lionel Royce as German

George J. Lewis as Huerta

Note: