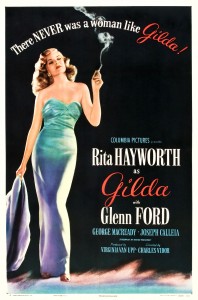

Viewed from a modernist perspective, Charles Vidor’s Gilda, made in 1946, is a significant erotic film, replete with ideas about sexual desire, both hetero and homosexual, as well as a classic film noir, using the language and vocabulary of that popular genre.

Our Grade: A- (**** 1/2 out of *****)

The film, which has become a cult item over the years, deals with many taboo issues, both implicitly and explicitly, prime among which is repressed sexuality, and the threat of libido to erupt at any time. Furthermore, the movie gains extra entertainment values from its dwelling on repression and depiction of the clash between Id, Ego, and Superego, to borrow useful concepts from Freudian psychology.

As a result, this feature has often been called “perverse,” what with its touches of sado-masochism and a byzantine-like plot that is never predictable. Gilda in fact revealed sexual repression and perversion (by standards of the time) of all sorts. At the time of its release, Gilda increased awareness in its viewers (male and viewers) about sexual mores and codes and practices that had been previously unheard of.

In particular, Rita Hayworth’s portrayal of Gilda as a sexually aggressive, dangerous, vampire-female was a new twist on the Hollywood heroine.

In one memorable (perhaps the most famous one) scene, which the conservative critic of the New York Times at the time simply deemed as “crude,” Hayworth feigns a striptease in black satin and long gloves.

Also, the two male leads, played by Glenn Ford and George Macready, have an extremely close relationship in the film, manifest in words, gestures, and looks, which today appears to be potentially or at least latently homosexual. These aspects of the film introduced viewers to new sexual worlds, in a stylish mode, and later on, an element of sophisticated camp was added by viewers who were looking and reading between the lines.

Gilda is significant because the film invented a new, liberated sexual world amid the pervasive sexual repression of the 1940s; the film was made just after WWII and the movie that swept all the Oscars that year was William Wyler’s The Best Years of Our Lives.

Subsequently, Rita Hayworth became the decade’s greatest pin-up girl, perhaps the first real one to follow Jean Harlow, a sex symbol in the 1930s, who died very young. Hayworth would be replaced as a sex goddess by the blond and voluptuous Marilyn Monroe. Of all three femmes, I thing Hayworth is the most interesting, partly because of her being a symbol of the dichotomy between sexual imagination and sexual realities.

When the U.S. Air Force sought a name for the Bikini atomic bomb, they appropriately chose “Gilda.” The analogy between an atomic bomb and a dangerous female was clearly made by the Air Force in this way. The name “Gilda” came to signify a wild woman.

Also, as the film was in many ways a played off of Casablanca‘s sexually repressed plot, manifest in the evolving intimate friendship and trust between Bogart’s and Claude Rains’ characters. This is confirmed by the film’s last image and sentence, when the two mean leave the airport, with Bogey saying: “Louis, this is the beginning of a beautiful friendship.”

Photo: Bogart and Bergman in Casablance.

It was as if Gilda uncovered and revealed more fully the sexual implications of that earlier beloved film, which won the 1943 Best Picture Oscar. Could it be that Hayworth’s overtly sexy–and sexual– performance also disclosed the truer nature of Ingrid Bergman’s role in Casablanca, which the film goes out of its way to portray as idealistic, patriotic, and ultimately more romantic than erotic.

Put the Blame on Mame

Through Hayworth’s performance, many female viewers were made aware of their inherent rights as women, long before the feminist implications of Thelma and Louise. One way Gilda achieved this effect was through the songs “Amada Mio” and “Put the Blame on Mame,” which Hayworth “sang” (actually dubbed) in the film. The lyrics of that song are about a woman who’s very much like Gilda: a woman who has been used and abused by men but comes to a realization that she does not have to put up with it anymore. The expression, in song lyrics, of Gilda’s determination to stand up against repression by men, had an even much greater impact than the film’s dialogue.

Gilda also contributed to the creation of camp culture, especially among sophisticated viewers, many of whom gay men. The movie might have been misunderstood upon its release because it was the first full-fledged camp film. Of course, campiness and self-reflection have since become widely accepted by Hollywood. For instance, no one would be shocked by a parody of Casablanca in this day and age. However, audiences in 1946 were uncertain about what Gilda was all about. Gilda set in motion an important part of popular culture that we take for granted now: Screen campiness.

The film ends with Gilda’s sexual reformation and redemption, and dismissal of the homoerotic inferences in the relationship between Glenn Ford and George Macready. Macreday, the obstacle to a “healthier” relationship between Ford and Hayworth, must be eliminated, and he is, though not the way you expected.

As the film was released in 1946 soon after World War II had ended and just as the Cold War was gaining momentum, it was important at this time to Hollywood to portray Americans as “normal” people, and Gilda had to end in this way. In the very last scene, it’s Gilda, now decently dressed in a suit, who says, “Let’s go home, Johnny,” meaning return to the U.S. and starting (from scratch) a new “domestic” lifestyle.

The film’s “happy ending,” with Gilda saying “Let’s Go Home Johnny,” with its implications of normalcy and domesticity, is too sudden, abrupt (and not very convincing, to say the least). After all the ordeals, rites, and tribulations they have gone through, could Johnny and Gilda become or assume a bourgeois middle class American couple? Here is a case of an incongruent and incoherent Hollywood movie, which, under pressure, was forced to please the censors of the Production Code Administration (PCA) as well as the expectations of more mainstream audiences.

I have never believed in that contrived happy ending, and I know, from screenings the picture in numerous film classes, that most of my students also have remained unconvinced. No resolution could really obscure the tabooed sexual issues that dominate the film–and ultimately gives it its raison d’etre and explains its current cult status.

Thinking of the movie, what linger in mind are images of Gilda’s black dress, stripping, and singing “Put the Blame on Mame.” In later years, award-winning costume designer Jean Louis referred to Hayworth’s black strapless gown as “the most famous dress I ever made,” an accomplishment he could not have anticipated or predicted.

Considered to be Hayworth’s best-known film, and the most iconic expression of her frequent on-screen teaming with Glenn Ford, Gilda was extremely commercial, earning over $3,750,000 rentals at the box-office.

Critical Status:

Credits:

n 2013, Gilda was selected for preservation in the U.S. National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being “culturally, historically or aesthetically significant.”

Directed by Charles Vidor

Produced by Virginia Van Upp

Screenplay by Jo Eisinger, Marion Parsonnet. Ben Hecht (uncredited), based on a story by E.A. Ellington

Cinematography Rudolph Maté

Edited by Charles Nelson

Production and distribution company: Columbia Pictures

Release date: March 14, 1946 (NYC)

April 25, 1946 (US)

Running time 110 minutes

Cast

Rita Hayworth as Gilda Mundson Farrell

Glenn Ford as Johnny Farrell

George Macready as Ballin Mundson

Joseph Calleia as Det. Maurice Obregon

Steven Geray as Uncle Pio

Joe Sawyer as Casey

Gerald Mohr as Capt. Delgado

Mark Roberts as Gabe Evans

Ludwig Donath as German

Don Douglas as Thomas Langford

Lionel Royce as German

George J. Lewis as Huerta