As a genre, the political crusading drama reappeared in the late 1940s, when Hollywood devoted its efforts to exploring racial discrimination, first against Jews, then against blacks and Indians.

As a genre, the political crusading drama reappeared in the late 1940s, when Hollywood devoted its efforts to exploring racial discrimination, first against Jews, then against blacks and Indians.

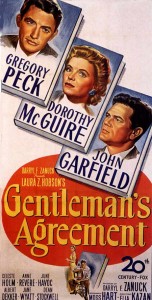

The 1947 Oscar-winning film was Elia Kazan’s Gentleman’s Agreement, based on Laura Z. Hobson’s novel and adapted to the screen by Moss Hart, which illustrated the cruelties and injustices of anti-Semitism.

Although “Gentleman’s Agreement” seems tame and naïve by today’s standards, it was definitely a big step in the maturation of Hollywood. Leonard Quart and Albert Auster have correctly noted that the political crusading dramas of the late 1940s and early 1950s conveyed “an optimism which refused to see any problem as insoluble,” but at least these films were directly confronting problems. Amazingly, “Gentleman’s Agreement” was the first time the word “Jew” was used explicitly in a mainstream film.

Kazan’s film was Hollywood’s first major attack on anti-Semitism. The director once said that the film was saying to the audience: “You are an average American and you are anti-Semitic. Anti-Semitism is in you.”

This film is supposed to have changed many people’s ideas about the treatment of Jews. Although the narrative examined anti-Semitism as it prevailed in the upper classes and professional worlds, thus entertaining the late 1940s “station-wagon-set,” “Gentleman’s Agreement” did bring the fundamental issue of anti-Semitism to the screen for the first time.

This film is supposed to have changed many people’s ideas about the treatment of Jews. Although the narrative examined anti-Semitism as it prevailed in the upper classes and professional worlds, thus entertaining the late 1940s “station-wagon-set,” “Gentleman’s Agreement” did bring the fundamental issue of anti-Semitism to the screen for the first time.

“Gentleman’s Agreement” set off a cycle of social problem films about racial issues, which included “Pinky” (1949), “Home of the Brave” (1949), “Intruder in the Dust” (1949), “Devil’s Doorway” (1949), “Broken Arrow” (1950), “Apache” (1954), “The Lawless” (1950), and “Viva Zapata!” (1952).

In the film, Gregory Peck plays a crusading journalist who decides to pose as a Jew in order to experience racial prejudice first-hand. All for the sake of a magazine article. Like most social consciousness films of the time, “Gentleman’s Agreement” also has a romance, here between the daughter (Dorothy McGuire) of Peck’s publisher and journalist Peck. McGuire turns out to be bigoted enough herself to nearly nix the affair; despite her intelligence, she just cannot shake her prejudices. In one of the film’s best lines, she tells Peck, “Don’t treat me to anymore lessons in tolerance. I’m sick of it!”

In the film, Gregory Peck plays a crusading journalist who decides to pose as a Jew in order to experience racial prejudice first-hand. All for the sake of a magazine article. Like most social consciousness films of the time, “Gentleman’s Agreement” also has a romance, here between the daughter (Dorothy McGuire) of Peck’s publisher and journalist Peck. McGuire turns out to be bigoted enough herself to nearly nix the affair; despite her intelligence, she just cannot shake her prejudices. In one of the film’s best lines, she tells Peck, “Don’t treat me to anymore lessons in tolerance. I’m sick of it!”

Two years after Gentleman’s Agreement, another message-political movie won Best Picture: All the King’s Men (1949). Read review below.

All the King’s Men (1949): Starring Broderick Crawford as Corrupt Politician

Detailed Plot

Gregory Peck stars as Philip Schuyler Green, a young widower journalist, has just moved to New York with his bright young son Tommy (Dean Stockwell) and kind mother (Anne Revere).

Green meets with magazine publisher John Minify (Albert Dekker), who asks Green–a gentile–to write an article on anti-semitism. He’s not very enthusiastic at first, but after initially struggling with how to approach the topic in a fresh way, Green is inspired to adopt a Jewish identity (“Phil Greenberg”) and writes about his first-hand experiences, just as he pretended to be a miner when he wrote about them. Green and Minify agree to keep it secret that Phil is not Jewish—as he is new to New York, it is easy to hide.

At a dinner party, Phil meets Minify’s divorced and rich niece Kathy Lacey (Dorothy McGuire), who is the person to originally suggest the story idea. Minify provides her with a large apartment and money, and she works as a pre-school teacher.

Phil tries to explain anti-Jewish prejudice to his precocious son – directly after displaying some anti-female prejudice of his own: “Some people don’t like other people just because they’re Jews.” Green is struck that the idea for the article came from “a girl” at the magazine. His mother replies, “Why, women will be thinking next.”

Phil has difficulty getting started, and it is only when his mother has heart pain one night, and he must summon a doctor, that he realizes he can never feel what another person feels unless he experiences it himself. He recalls having “lived as an Okie on Route 66 or as a coal miner for previous writing jobs. He decides to write a piece titled, “I Was Jewish for Six Months”.

Though Kathy seems to be liberal, but when he reveals his intentions, she is taken aback and asks if he actually is Jewish. There is a strain on their relationship due to Kathy’s subtle acquiescence to bigotry.

At the magazine, Phil is assigned a secretary, Elaine Wales (June Havoc), who reveals that she too is Jewish. She changed her name in order to get the job (her application under her real, Jewish-sounding name, Estelle Wilovsky, was rejected). After Phil informs Minify about Wales’ experience, Minify orders the magazine to adopt new hiring policies. Wales has reservations, fearing that the “wrong Jews” will be hired and ruin things for the few Jews working there. Phil then meets fashion editor Anne Dettrey (Celeste Holm), who becomes a good friend, particularly as strains develop between Phil and Kathy.

Phil’s childhood friend, Dave Goldman (John Garfield), who is Jewish, moves to New York for a job and lives with the Greens while looking for a home for his family. Housing is scarce in the city, but it is particularly difficult for Goldman, since some landlords will not rent to a Jews. When Phil tells Dave about his project, Dave is supportive but concerned.

Kathy’s attitudes are revealed further when she and Phil announce their engagement. Her sister Jane (Jane Wyatt) invites them to her home in Darien, Connecticut, a “restricted” community where Jews are not welcome. Fearing an awkward scene, Kathy wants to tell her friends that Phil is only pretending to be a Jew, but Phil asks Kathy to tell only Jane. At the party, everyone is friendly to Phil, though many people are “unable” to attend at the last minute.

Dave feels that he will have to quit his job because he cannot find a residence. Kathy owns a vacant cottage in Darien, but though Phil sees it as the obvious solution to Dave’s problem, Kathy is unwilling to offend her neighbors by renting it to a Jew. She and Phil break their engagement, and Phil plans to move out of New York when his article is published. When it comes out, it is well received by the magazine staff.

Kathy meets with Dave and tells him how sick she felt when a party guest told a bigoted joke. However, she has no answer when Dave asks her what she did about it. She is forced to realize that her silence condones prejudice.

Dave tells Phil that he and his family will be moving into the cottage in Darien, and Kathy will be moving in with her sister next door to make sure they are treated well by neighbors. When Phil hears this, he reconciles with Kathy.

“Gentleman’s Agreement” was praised by most critics, with one finding it to be “more savagely arresting and properly resolved as a picture than it was as a book,” and describing its script as “electric with honest reportage.” Its major competitor for the Oscars of 1947 was Edward Dmytryk’s “Crossfire,” which lost in each of its five nominated categories. “Crossfire”‘s nominated screenplay, by John Paxton, was based on Richard Brooks’s novel The Brick Foxhole, though in a typically Hollywood manner it changed the book’s homosexual hero into a Jew.

In retrospect, many critics feel that “Crossfire” is a better film than “Gentleman’s Agreement” in every aspect: theme, characterization, acting, and visual style. Also dealing with racial bigotry, although more disguised, it was directed by Dmytryk as a tense noir thriller about an obsessive, psychopathic sergeant (Robert Ryan, who specialized in this kind of role), who beats a Jewish ex-sergeant to death. Detective Finlay (Robert Young), helped by sergeant Keely (Robert Mitchum), sets out to trap the killer. Like Gentleman’s Agreement, it is a heavy message film, with many speeches against prejudice, but it boasts great acting by Ryan and Gloria Grahame, as a floozy dance hall girl, who were both nominated for supporting awards.

That “Gentleman’s Agreement” was voted Best Picture more for ideological than considerations is clear not only from its win over “Crossfire, but also in its win over David Lean’s masterpiece, “Great Expectations.” The Academy proved that when weighing a film’s contents against its style, the former counts more. “Gentleman’s Agreement” won two other awards, for Director Kazan, and for Supporting Actress Celeste Holm, who had all the biting dialogue.

Memorable Lines:

Anne (Celeste Holm): “Tell me, why is it that every man who seems attractive these days is either married or barred on a technicality?”

Cast

Gregory Peck as Philip Schuyler Green

Dorothy McGuire as Kathy Lacey

John Garfield as Dave Goldman

Celeste Holm as Anne Dettrey

Anne Revere as Mrs. Green

June Havoc as Elaine Wales

Albert Dekker as John Minify

Jane Wyatt as Jane

Dean Stockwell as Tommy Green

Sam Jaffe as Professor Fred Lieberman

Nicholas Joy as Doctor Craigie