“ Don’t you gaslight me,” meaning “Don’t try to drive me crazy,” became a popular expression in 1944 based on the noir thriller “Gaslight.”

Don’t you gaslight me,” meaning “Don’t try to drive me crazy,” became a popular expression in 1944 based on the noir thriller “Gaslight.”

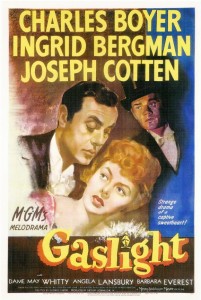

George Cukor’s suspenseful melodrama is a remake of the British film, released in the U.S. as “Angel Street” (aka “Murder in Thornton Square”), starring Anton Walbrook and Dianna Wynyard.

When MGM decided to remake the film, it bought the rights to Thorold Dickinson’s version and withdrew the movie from circulation, causing a lot of resentment in the British industry.

“Gaslight” is based on Patrick Hamilton’s play, which premiered in London in 1938, then ran on Broadway for two years.

Nominated for eight Oscars, it’s one of Cukor’ best pictures and one of MGM’s most accomplished noir melodramas of the 1940s. Cukor’s film, which is half an hour longer than the British film, is smoother, richer in psychological detail, and more artfully executed.

Nominated for eight Oscars, it’s one of Cukor’ best pictures and one of MGM’s most accomplished noir melodramas of the 1940s. Cukor’s film, which is half an hour longer than the British film, is smoother, richer in psychological detail, and more artfully executed.

The superbly crafted script, co-written by John Van Druten and Walter Reisch, moved the action effectively out of the stage’s confines; the picture doesn’t betray its theatrical origins.

After their honeymoon, Anton (Charles Boyer) sets out to drive his young cherubic wife (Ingrid Bergman) insane so that he can conveniently put her in an asylum and steal the precious jewels hidden in their house, where he had murdered her aunt Alice, a rich, renowned soprano. The title derives from the gas jet in Paula’s bedroom, which ominously dims whenever her husband turns on the gas lamp in the attic in his obsessive search through Alice’s possessions.

The flickering flames increase Paula’s fear that her rational faculties are beginning to weaver. Cukor follows Hitchcock in tipping off the audience early on the husband’s greed and duplicity. By giving this vital information away, before the heroine herself finds out, tension builds steadily. In the touching climax, Paula finds out that her husband had never loved her, that he had been enslaved to his obsessive addiction to diamonds.

The flickering flames increase Paula’s fear that her rational faculties are beginning to weaver. Cukor follows Hitchcock in tipping off the audience early on the husband’s greed and duplicity. By giving this vital information away, before the heroine herself finds out, tension builds steadily. In the touching climax, Paula finds out that her husband had never loved her, that he had been enslaved to his obsessive addiction to diamonds.

There’s an ironic note to Paula’s revenge–Anton discovers the gems (embroidered on Alice’s gown) just before going to prison.

Please read our review of Ingrid Bergman’s second Best Actress Oscar performance (below)

Anastasia (1956): Ingrid Bergman’s Oscar-Winning Comeback Performance

The key symbol of the fluttering gaslight is established during the credits sequence, while Alice’s voice is heard on the soundtrack. The spirit of the dead soprano haunts the house where she was strangled.

Cedric Gibbons deservedly won an Oscar for supervising the art direction. The set decoration is by Paul Huldchinsky, a German refugee who borrows elements from German expressionist style in making the house cluttered and stifling, imbued a claustrophobic jail-like atmosphere. The movie received an Oscar for interior decoration (as it was then called).

Ingrid Berman, who won the first of her three Oscars for this film, is terrific as the fragile bride terrorized by her husband’s dirty tricks. The Oscar cemented Bergman’s reputation as Hollywood’s most popular actress, having made Casablanca and For Whom the Bell Tolls the year before. Hitchcock later cast Bergman in Spellbound” and Notorious.

Angela Lansbury’s Stunning Debut

Angela Lansbury was unknown when Cukor cast her as Nancy, the conniving maid who tries to lure Anton away from his wife. Lansbury tested for the role, and Cukor was impressed with her poise, the way she carried herself, and her Cockney accent. Nonetheless, the director decided she was too young for the role, which sent Lansbury back to Bullocks and working as a cosmetics girl. A week later, after looking at Lansbury’s screen test again, Cukor asked for a second audition, which turned out to be even better than the first. Cukor then had her role expanded.

Angela Lansbury was unknown when Cukor cast her as Nancy, the conniving maid who tries to lure Anton away from his wife. Lansbury tested for the role, and Cukor was impressed with her poise, the way she carried herself, and her Cockney accent. Nonetheless, the director decided she was too young for the role, which sent Lansbury back to Bullocks and working as a cosmetics girl. A week later, after looking at Lansbury’s screen test again, Cukor asked for a second audition, which turned out to be even better than the first. Cukor then had her role expanded.

Rising to 5’8″, Lansbury was the same height as Bergman. To make her more menacing, Cukor asked Lansbury to wear platform shoes. Lansbury’s stunning debut in Gaslight garnered her with her first, supporting, Oscar nomination.

Cukor was also persuasive in getting Charles Boyer to play first outright villainous role; before that, Boyer mostly played romantic roles opposite Garbo (“Conquest”), Hedy Lamarr (“Algiers”), Irene Dunne (“Love Affair”).

A thriller soaked in paranoia, “Gaslight” is a period films noir that, like Hitchcock’s “The Lodger” and “Hangover Square, “is set in the Edwardian age.

Cycle of Film Noir: Women as Victims

It’s interesting to speculate about the prominence of a film cycle in the 1940s that can be described as “Don’t Trust Your Husband.” It began with three Hitchcock films: Rebecca (1940), Suspicion (1941), and Shadow of a Doubt (1943), and continued with Gaslight and Jane Eyre (both in 1944), Dragonswyck (1945), Notorious and The Spiral Staircase (both 1946), The Two Mrs. Carroll (1947), and Sorry, Wrong Number and Sleep My Love (both in 1948).

It’s interesting to speculate about the prominence of a film cycle in the 1940s that can be described as “Don’t Trust Your Husband.” It began with three Hitchcock films: Rebecca (1940), Suspicion (1941), and Shadow of a Doubt (1943), and continued with Gaslight and Jane Eyre (both in 1944), Dragonswyck (1945), Notorious and The Spiral Staircase (both 1946), The Two Mrs. Carroll (1947), and Sorry, Wrong Number and Sleep My Love (both in 1948).

All of these films use the noir visual vocabulary and share the same premise and narrative structure: The life of a rich, sheltered woman is threatened by an older, deranged man, often her husband. In all of them, the house, usually a symbol of sheltered security in Hollywood movies, becomes a trap of terror.

End Note

Terry Moore (credited as Jan Ford), who will become a major actress in 1950s melodramas (“Come Back, Little Sheba,” “Peyton Place”) plays the Ingrid Bergman’s character as a young girl.

Cast

Charles Boyer as Gregory Anton

Ingrid Bergman as Paula Alquist Anton

Joseph Cotten as Brian Cameron

Dame May Whitty as Miss Bessie Thwaites

Angela Lansbury as Nancy Oliver

Barbara Everest as Elizabeth Tompkins

Emil Rameau as Maestro Guardi

Edmund Breon as General Huddleston

Halliwell Hobbes as Mr. Mufflin

Tom Stevenson as PC Williams

Heather Thatcher as Lady Mildred Dalroy

Lawrence Grossmith (in his last film role) as Lord Freddie Dalroy

Terry Moore as Paula Alquist – Age 14 (uncredited)

Morgan Wallace as Fred Garrett

Alec Craig as Turnkey