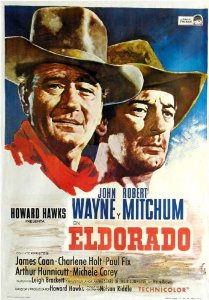

Following John Wayne’s Western McLintock! by four years, and Howard Hawks’ Rio Bravo by eight, El Dorado, also directed by Hawks, is a work that’s as significant sociologically as it is cinematically.

Grade B: (**** out of *****)

The film’s point of departure was Harry Brown’s “The Stars in Their Course,” but director Howard Hawks and frequent screenwriter-collaborator Leigh Brackett borrowed substantially from Rio Bravo in plot and characterization, turning this 1967 Western into sort of a sequel.

A third installment in the series-like saga, Rio Lobo, would be released in 1970, Though more violent and more repetitious than “Rio Bravo,” “El Dorado” is still superior to the last panel, “Rio Lobo,” in every respect.

Note:

If you want to know more about John Wayne’s career and Life, please read my book:

Leigh Brackett said in a later interview that her original script was “the best script I had ever done in my life. It wasn’t tragic, but it was one of those things where Wayne died at the end.” However, she said that the closer they got to production “the more we got into doing Rio Bravo over again, the sicker I got, because I hate doing things over again. And I kept saying to Howard I did that, and he’d say it was okay, we could do it over again.”

El Dorado became yet another filmic variation of Hawks’ two favorite themes, professional competence and male camaraderie.

And because the director is aware that John Wayne is older and unable to play the kind of hero he had embodied in Rio Bravo, El Dorado examines the impact of age and how Wayne and the other characters deal with their declining abilities, on and off screen.

On the surface, though, the narrative concerns a drunken sheriff (Robert Mitchum), helped by a gunfighter (John Wayne) in his fight against a greedy landlord (Edward Asner).

John Wayne and Robert Mitchum play old friends who have not seen each other for a long time. Throughout the film, they test each other’s abilities. “I just wanted to see if you’ve slowed down,” Wayne tells Mitchum in a crucial scene, to which the latter replies, “Not that much.”

El Dorado depicts Wayne’s (and Hawks’) fearful awareness of a man’s declining strength and diminishing professional skills that inevitably come along with aging and slowing down.

For example, the doctor refuses to take the bullet out of Wayne, because “I’m not good enough.” James Caan relies on a knife, because he is not good enough with a gun; he learns to use it from Wayne, who is good enough to teach him. Wayne also takes him to a gunsmith who is good enough to know what weapon Caan should use, to make up for his limitations.

Later on, Caan defends his (dead) friend, accused of cheating at cards, claiming, “he was good, he didn’t have to cheat.”

Other Hawksian motifs, which also reflect Wayne’s credo, are courtesy and respect–even for the enemy. Wayne and the hired gunslinger Dan McLeod respect each other, because they know they are both good. And Wayne says he’s intrigued by “a little question unanswered between us,” that is, who is better with the gun.

Still later, Wayne shoots down McLeod several times, with the dying McLeod protesting, “You didn’t give me any chance at all, did you” To which Wayne replies, “No, I didn’t. You were too good to give a chance to.”

Critical Response

Most critics singled out the film’s autobiographical themes, which were not necessarily its strongest assets. “Humor and affirmation on the brink of despair are the poetic ingredients of the Hawksian Western,” wrote eloquently the movie critic Andrew Sarris in the Village Voice (July 27, 1967). “And now memory. Especially memory. Only those who see some point in remembering movies will find “El Dorado” truly unforgettable.” Sarris liked the film’s message, namely, that life is hard on heroes, but they must go on in good humor, even if they have to walk on crutches to gunfights.

“Time” magazine also praised John Wayne and Robert Mitchum, who “with crutches as swagger sticks, they limp triumphantly past the camera–two old pros demonstrating that they are better on one good leg a piece than most of the younger stars are on two.”

However, the British critic Philip French found it repetitious, due to the fact that “about every five minutes someone says, “Because I’m not good enough.” French did not like the film because it was “inordinately slow,” and “so talkative.”

Similarly, the “New Yorker”critic Pauline Kael thought that Wayne and Mitchum parodied themselves, looking, just as the film itself, exhausted, as if they were acting in a late episode of a television series.

Other critics did not like the idea that, except for the opening action scene, (orchestrated by a second unit), the movie was shot on the studio back lot–and it felt that way.

Cast

John Wayne as Cole Thornton

Robert Mitchum as Sheriff J.P. Harrah

James Caan as Alan Bourdillion Traherne (nicknamed “Mississippi”)

Arthur Hunnicutt as Bull Harris

Charlene Holt as Maudie

Michele Carey as Josephine “Joey” MacDonald

Ed Asner as Bart Jason

Christopher George as Nelse McLeod

R. G. Armstrong as Kevin MacDonald

Paul Fix as Dr. Miller

Credits:

Produced. directed by Howard Hawks

Screenplay by Leigh Brackett, Based on the 1960 novel, “The Stars in Their Courses,” by Harry Brown

Music by Nelson Riddle

Cinematography Harold Rosson

Edited by John Woodcock

Production company Laurel Productions

Distributed by Paramount Pictures

Release date: June 7, 1967

Running time 126 minutes

Budget $4,653,000

Box office $5,950,000