Vincente Minnelli’s Designing Woman began as a sketch by Metro’s costume designer, Helen Rose.

Grade: B (*** out of *****)

| Designing Woman | |

|---|---|

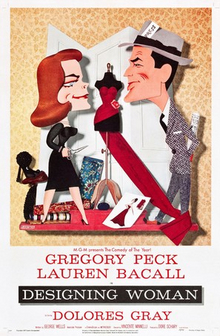

Theatrical release poster

|

|

Rose’s story is basically lifted out of George Stevens 1942 classic comedy, Woman of the Year, a far better movie, which represented the first teaming of Katharine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy in a long series of collaborations.

The “new” film concerns a sleek designer (Lauren Bacall, in the Hepburn role) and a rumpled sportswriter (Gregory Peck, in the Tracy role) who wed in haste, only to realize their “irreconcilable differences,” and the incompatibility between her chic friends and his crass cronies. Complications arise with the reappearance of the groom’s old flame, a musical star. More than the tale itself, the studio liked the snappy title, hoping that with the right stars Designing Woman would be a success.

Minnelli decided to cast against type Gregory Peck as the groom. Hardly skilled as a comedian, Peck, who had just made dramas like “Moby Dick” and “The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit,” found it a refreshing change of pace. Peck’s deal guaranteed leading lady approval, and he supported Minnelli’s choice of Lauren Bacall, with whom he was friendly.

Bacall had previously replaced Grace Kelly once, on Minnelli’s melodrama, The Cobweb. Though not flattered for being a replacement, Bacall needed to work after a long and intense period of taking care of her dying husband, Humphrey Bogart.

As the vamp, Dolores Gray substituted for the originally cast Cyd Charisse. For the heroine’s choreographer pal, a neurotic, effeminate artsy type, Minnelli selected choreographer Jack Cole, even though he had never acted before. Cole was also asked to choreograph the films dance numbers, as he had done for Minnelli’s Kismet.

“Designing Woman” receives a glossy treatment from cameraman John Alton, who had just shot Minnelli’s “Tea and Sympathy,” Preston Ames, who designed the requisite Manhattan glamour, and Helen Rose, who was in charge of the elegant costumes. Shooting began on September 10, 1956 and concluded ten weeks later, with only two exterior locations, at the Newport Beach harbor and the Beverly Hills Hotel.

Aiming to recapture the glamour of Hollywood’s 1930s and 1940s screwball comedies, the film has the glossy look of studio-manufactured entertainment. “Designing Woman” boasts high production values at the expense of an original script.

However, in one of Oscar Awards inexplicable scandals, George Wells’ shopworn script was honored with the Best Original Screenplay. This was a glaring choice in a year that saw competition from Fellini’s “I Vitellloni,” “Funny Face,” “The Tin Star,” and “Man of a Thousand Faces.”

The story features a gallery of types familiar from 1930s comedies: tart-tongued working- women, Runyonesque gangsters, scrappy editors, and so on. The plots gimmick is a throwback: Protagonist Marilla (Bacall) gets angry not at the prospect of an actual affair between her husband and the voluptuous dancer Lori Shannon, but at his past affair with Lori.

Minnelli’s reliable tempo and droll sense of chic sustains the movie, even though it lacks that zesty wit and energy of the old comedies. Minnelli saturates the screen with glamour, which contributes to a fluffy pleasurable fare.

Mobsters threaten Mikes life to squelch a hot story, but they are soft-spoken gangsters, deferent to the ladies; the worse they can do is to punch Mike’s nose. They are certainly not as dangerous as his spurned fiancee, Lori Shannon, who dumps a spaghetti dish into the lap of Mikes suit over lunch.

Peck is too squeaky-clean and well groomed to play a working journalist. Since neither Peck nor Bacall are deft at physical farce, the slapstick that Tracy and Hepburn or Cary Grant and Hepburn could effortlessly do falls flat here. There are semi-funny scenes, such as the one in which Marilla nearly collapses at the boxing match, or Mikes parody of choreographer Randy’s body language. As noted, a similar scene appeared in Tea and Sympathy, when the effeminate Tom is taught how to walk like a real man.

Occasionally, Minnelli succumbs to low-comedy tricks. Mikes self-appointed bodyguard, Maxie (Mickey Shaughnessy), is a paranoid pugilist, who sleeps with his eyes open and is comatose when awake. When Marilla expresses distaste for the fighter’s profile, Mike says, “He has a nose. It’s inside.” This bit feels like a tribute to Aldo Rays role in Cukor’s 1952 comedy, Pat and Mike, with Tracy and Hepburn; its no coincidence that Pecks hero is called Mike.

But Minnelli gives Designing Woman a visual playfulness, with energetic camera movements and other visual tricks. Once again, Minnelli’s flamboyant touches turn a stale comedy into a more lavish and polished fare than it has the right to be. One scene stands out: Seen through Mike’s hangover, Beverly Hills is a psychedelic landscape of chartreuse palms against pinkish skies. In another scene, jump-cut close-ups punctuate Marilla’s realization that the girl in Mike’s torn photo is Lori, the star of the show shes designing.

Minnelli’s favorite prop, the mirror, is the focus of an elaborate camera set-up. When Lori pauses to adjust her makeup, Marilla’s reflection is seen, wearing one of Minnellis a red, red suits, which easily upstages Lori. The camera tracks backward as Marilla bursts into the restaurant, while Lori examines the bride in the background.

The theatrical milieu allows for a musical number to be staged with some verve and wit. For the big moment of Dolores Grays the queen of TV variety, Minnelli employs two choruses.

Minnelli enjoys repeating the recurrent theme of performers grace under pressure. A run-through of “There’ll Be Some Change Made,” during which star belts out her song and makes love to the camera. Running between two sets in a dash, she changes from a great lady in pastels to a siren in sea-foam lame, while studio minions fiddle with her accessories. The TV camera and microphone boom underscore the song with rolling movements of the own.

Cast

Gregory Peck as Mike Hagen

Lauren Bacall as Marilla Brown Hagen

Dolores Gray as Lori Shannon

Sam Levene as Ned Hammerstein, Mike’s editor

Tom Helmore as Zachary Wilde, Marilla’s former boyfriend

Mickey Shaughnessy as Maxie Stultz, a punch-drunk ex-boxer friend of Hagen

Jesse White as Charlie Arneg

Chuck Connors as “Johnny O”, one of Daylor’s henchmen

Edward Platt as Martin J. Daylor

Alvy Moore as Luke Coslow

Carol Veazie as Gwen

Jack Cole as Randy Owens

Richard Deacon as Larry Musso (uncredited)

Dean Jones as assistant stage manager in Boston (uncredited)

Sid Melton as Miltie, henchman (uncredited)

Credits:

Directed by Vincente Minnelli

Written by George Wells, based on a story by Helen Rose

Produced by Dore Schary

Cinematography John Alton

Edited by Adrienne Fazan

Music by Billy Higgins, André Previn, W. Benton Overstreet

Distributed by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

Release date: May 16, 1957

Running time: 118 minutes

Budget $1.8 million

Box office $3.7 million