“Benjamin Button” represents the same, welcome change of pace for its director-auteur David Fincher that “Slumdog Millionaire” represents for Danny Boyle. It may be premature to predict, but as of today, “Benjamin Button” and “Slumdog Millionaire” are the two best pictures of the year, based on their original conception and superlative accomplishment.

With “Benjamin Button,” which ironically is his first PG-13 picture, Fincher reaffirms his status as one of the most innovative directors working today. Remarkably, with a relatively small output to his credit–only 7 features in 16 years–Fincher has managed to do experimental work within the confines of the studio system, without ever repeating himself. Though some themes run across all of his output, each of his films is different narratively, visually, and technically.

Putting state-of-the-art technology to most effective use, “Benjamin Button” does proud to Hollywood. It’s a big, massive, uniquely American tale, which combines special effects with splendid performances that are not buried under the heavy weight of eye-grabbing CGI.

The main problem resides in the storytelling, the sprawling script penned by Eric Roth, which less than building up or continuing a saga, just stops too many times and then begins again. As a result, Benjamin Button is a movie that’s easier to respect (or even admire), but harder to connect to, or feel much for, the tale and its lead character.

Even so, here is a movie that, unlike other highlights this year, such as “Revolutionary Road,” “Doubt,” and “Frost/Nixon,” can never be mistaken as an extension of literature (the former) or theater (the latter).

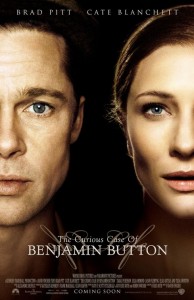

“Benjamin Button” should receive about 10 (or more) Oscar nominations across the board: Best Picture, Director (Fincher has never been nominated), Screenplay, Actor (Pitt), Actress (Blanchett), several Supporting Actors and Actresses, and of course, a sweep of the technical categories: Special Effects, Sound Effects, Production Design, Make-Up.

Make no mistake, the premise is taken from F. Scott Fitzgerald’s 1921 short story of the same title, about a man who is born in his eighties and ages backwards. But Fincher’s picture is a very loose adaptation of its source material, and much richer, not least because of its new locale, New Orleans (Fitzgerald’s story is set in Baltimore), epic scale, and narrative scope, which spans almost an entire century, from 1918, when the hero is born, up to the present, the Katrina disaster in New Orleans.

If in its high levels of aspiration and execution, and undeniably exuberant joy of filmmaking, “Benjamin Button” bears resemblance to “Slumdog Millionaire,” in structure, tone, and theme, the film is a companion piece to “Forrest Gump.” The reason for this similarity is rather simple: Both pictures are scripted by Eric Roth, who won an Oscar in 1994. The new film also credits the work of Robin Swicord on a previous version of the scenario. (The project has been in development, in various forms and with different directors attached, for over a decade).

Let me be more specific in the comparison of the two films. Like “Forrest Gump,” “Benjamin Button” represents a grand, massive yet cohesive tale of a not-so-ordinary man, the people and places he discovers along the way, the affairs and adventures he goes through, the joys of life and the sadness of deaths he faces, and the exhilarating experience of something that goes beyond time, eternal love. (“Slumdog Millionaire” also celebrates pre-destined romantic love).

“I was born under unusual circumstances,” says Benjamin (Brad Pitt) at the beginning of this magical yarn about a man who is born in his eighties and ages backwards. Both ordinary and extraordinary, Benjamin is like any of us, a man who is unable to stop time. We follow his story, set in New Orleans from the end of World War I in 1918, into the 21st century, tracking a journey that’s as fascinating and unusual as any man’s life can potentially be–only more so.

In “Forrest Gump,” director Robert Zemeckis showed shrewdness and technical skill in turning dubious material into a uniquely poetic American comedy. The picture’s Oscars and phenomenal commercial success suggested that it touched deep chords in the American public consciousness (and among Academy voters). It remains to be seen how exactly will “Benjamin Button” connect with the audience in the zeitgeist of the post 9/11 era.

That film’s hero (played by Tom Hanks) was a retarded man but blessed with innate decency and huge courage. Forrest is simple, but his heart is always in the right place. “Forrest Gump” implies that we, the viewers, could be as good and patriotic citizens as Forrest Gump, if only we could have the courage to be simple and naive. Veiled with cool technology, the film was so smart that many viewers disregarded its sanctimonious tone, and that it packaged innocence as a more desirable state of being.

Trusting its audience’s intelligence, “Benjamin Button” makes no such assumprions or demands. The hero may be simple, but the movie is not, a function of Fincher’s more cynical philosophy and modernist aesthetics than those defining Zemeckis work circa 1994. Even so, like Forrest Gump, as a character, Benjamin belongs to the same type of men that are at the center of such seemingly diverse narratives as “King of Hearts,” “Being There” (1979), with an Oscar-nominated role by Peter Sellers, “Rain Man” (1988), which brought a second Oscar to Dustin Hoffman. Unlike those protags, however, Pitt plays his role in a straightforward manner, without condescension or gimmickry.

This is the third successful teaming of Fincher and Pitt, who starred in the helmer’s best features, “Seven” (1995) and “The Fight Club” (1999). Essaying his most demanding and complex role to date, one that should garner him his first Best Actor Oscar nomination, Pitt begins as a character who may be naïve and limited in consciousness, but is generous in feeling and heart, hence facilitating the audience’s identification with him. As the glue that holds the episodic film together, Pitt never allows his persona’s eccentricities to become comedic or satiric caricature.

This odd epic tale of a man who ages backwards unfolds as a series of set-pieces that pay impeccable attention to the time and setting in which they take place. What unifies the film, other than Pitt’s character and his first-person voice-over narration, is a framing device, a contemporary hospital setting.

Hence, the tale begins at the present time in a New Orleans’ hospital, in which Daisy (Cate Blanchett), Benjamin’s grand amour, is dying. Her concerned daughter Caroline (Julia Ormond) is at her bedside, reading to her from his personal diary, which is full of scribbled notes, photos, and postcards. It’s hard to tell why Fincher felt the need to return one too many times to the hospital scene, often just for one sentence or a single observation–perhaps to remind us that what we are watching is related from Benjamin’s subjective and consistent perspective. It’s one of the film’s few structural weaknesses, interrupting the otherwise smooth flow of events and also prolonging the running time.

Most of the richly textured yarn, however, consists of chapters, dozens of them, each fastidiously created and meticulously related. In terms of storytelling, the whole movie is seamless, which is not a minor feat, considering the film’s length (close to three hours) and large number of flashback episodes (at least 30).

The saga begins with a strange-looking baby, small but already wrinkled, dropped by a white man at the steps of an old-age home. He is soon picked up by Queenie (a marvelous Taraji P. Henson), a sensitive attendant, who raises him as her own son; he calls her mamma to everyone’s surprise. Unbeknownst to him, Benjamin does have biological parents: His mother died at child birth and his father (Jason Flemying) appears and disappears in his life, often in the least expected moments, resulting in a peculiar bonding between the two men, based on one-sided ignorance but mutual respect and caring.

Though a child, Benjamin is bald, hearing-impaired, wears heavy glasses, and is placed on a wheelchair, all elements that make him more of an “insider” among other old men and women, mostly members of the Southern upper-class. Throughout the narrative, Benjamin returns to Queenie’s place, only to face time and again “bad news,” usually tales of deaths of this and that person of his life.

Like Forrest Gump, early on, Benjamin falls for a young, red-haired girl named Daisy (played by different actresses, among them Elle Fanning, before Blanchett takes over as a young woman), the granddaughter of a kind matron, who had taught him how to play the piano. Daisy, of course, is the name of the protag of Fitzgerald’s famous novel, “The Great Gatsby,” which the movie alludes to visually by making Pitt look like Robert Redford, who starred in the 1974 Hollywood version alongside Mia Farrow.

The text is laced with one good recurrent joke, an older man who keeps telling Benjamin, “Did I ever tell how I was struck by lightning seven times in my life,” which is followed by visual illustrations of this motif, each time assuming different ideas, shapes and forms.

A loose string of vignettes, presented by Fincher at a varied pacing, the film establishes Benjamin as a passive hero, sort of a reactor or (accidental) emblem of his times. He’s a timid man-boy, or boy-man, depending on the phase of the story, whose passivity and sometimes slowness are balanced by a genuinely sweet nature and open-mindedness to new experiences, including booze, women, and adventures out on a wild boat.

It’s a tribute to Fincher’s consistently deft touch that, despite the heavy use of special effects, and the fact that death is the most recurrent motif in Benjamin’s story, the movie as a whole is not sad or depressing, just melancholy and lyrical, and in moments extremely touching and even poetic. The last scene, in which Benjamin, an old man as a baby, is held in the arms of Daisy, the love of his life, might reduce you to tears.

If the corny “Forrest Gump” made you feel bad about enjoying it, “Benjamin Button,” a far more cerebral and existential tale, should make you contemplative and meditative about issues of life and death, fate, predestination, and random circumstances, above all, romantic love.

It’s a pleasure to report that Pitt meets the enormous challenge called by his multi- nuanced, endlessly shifting role with considerable charisma and panache. Though aging from 80 to a baby, he’s always recognizable as Pitt (I mean that as a compliment), through his voice or other physical and emotional attributes. We delight in watching him go through the ages and the motions, and take pleasure in his looks. The midsection, which display Pitt at his most handsome, inevitably reads like a catalogue of his two-decade screen career, from the hunks he played in “Thelma & Louise” (1991) and othern films all the way to the gray-haired maturity he showed in “Babel” (2007).

Cate Blanchett, who plays an impossibly difficult role, occasionally stumbles, both as a younger and older figure. Her story as a dancer is one of the film’s weakest subplots, but she becomes most interesting as she ages, and should be commended for maintaining a coherent interpretation even while lying immobile in a hospital bed and covered with tons of make-up.

The rest of the cast all shines, especially Taraji P. Henson, Jared Harris, Tilda Swinton, Jason Flemyng, Elias Koteas and Julia Ormond.

Replete with rich images and symbols, “Benjamin Button” is a field day for semioticians and structuralists. Take the feature’s opening and closing symbolic sign, a huge clock. When the saga begins, Daisy tells us that the clock was built by a craftsman named Monsieur Devereux (Canadian Elias Koteas) as a tribute to his lost son, a WWI fighter. After that, Devereux simply disappeared, but not his creation, which decorates the glorious New Orleans train station. At the end of the journey, after hurricane Katrina hits hard, the last image in the movie is of the same clock, washed by water, crushed on the floor.

The lush, impressive score of “Benjamin Button” was written by French composer Alexandre Desplat, who recorded his score with an 87-piece ensemble of the Hollywood Studio Symphony at the Sony Scoring Stage.

Cast

Benjamin Button – Brad Pitt

Daisy – Cate Blanchett

Queenie – Taraji P. Henson

Caroline – Julia Ormond

Thomas Button – Jason Flemyng

Tizzy – Mahershalalhashbaz Ali

Captain Mike – Jared Harris

Monsieur Devereux – Elias Koteas

Grandma Fuller – Phyllis Somerville

Elizabeth Abbott – Tilda Swinton

Preacher – Lance Nichols

Ngunda Oti – Rampai Mohadi

Daisy age 7 – Elle Fanning

Daisy age 10 – Madisen Beaty

Credits

A Paramount (in U.S.) and Warner (international) release and presentation of a Kennedy-Marshall production.

Produced by Kathleen Kennedy, Frank Marshall, Cean Chaffin.

Directed by David Fincher.

Screenplay, Eric Roth; story by Roth and Robin Swicord, based on a short story by F. Scott Fitzgerald.

Camera: Claudio Miranda.

Editors, Kirk Baxter, Angus Wall.

Music: Alexandre Desplat.

Production designer: Donald Graham Burt.

Supervising art director: Tom Reta.

Art directors: Randy Moore (Los Angeles), Scott Plauche, Kelly Curley (New Orleans), Michele Laliberte (Montreal).

Set designers: Lorrie Campbell, Jane Wuu, Clint Wallace, Randy Wilkins, Tammy Lee, Masako Masada, Ryan Heck (New Orleans).

Set decorator: Victor J. Zolfo.

Costume designer: Jacqueline West.

Sound: Mark Weingarten.

Sound designer-supervising sound editor: Ren Klyce.

Re-recording mixers: David Parker, Michael Semanick, Klyce.

Visual effects supervisor: Eric Barba.

Visual effects and animation: Digital Domain. Visual effects: Asylum, Lola Visual Effects, Matte World Digital, Hydraulx, Ollin Studio, Savage Visual Effects.

Special effects coordinator: Burt Dalton. Special makeup: Greg Cannom.

Makeup effects supervisor: Brian Sipe.

Stunt coordinator: Mickey Giacomazzi.

Associate producer: Jim Davidson.

Assistant director: Bob Wagner.

Second unit director (India and Cambodia), Tarsem.

Second unit camera: Dan Holland.

Casting: Laray Mayfield.

MPAA Rating: PG-13.

Running time: 166 Minutes.