Otto Preminger’s The Man with the Golden Arm was a landmark film in several ways. It was the first time that a Hollywood film squarely faced the problem of drugs in America. Secondly, the film established a new independence for Hollywood films from the long, stifling reign of the Hays Office and the Legion of Decency. In the course of doing that, “Man with Golden Arm” became the topic of a heated public debate.

Otto Preminger’s The Man with the Golden Arm was a landmark film in several ways. It was the first time that a Hollywood film squarely faced the problem of drugs in America. Secondly, the film established a new independence for Hollywood films from the long, stifling reign of the Hays Office and the Legion of Decency. In the course of doing that, “Man with Golden Arm” became the topic of a heated public debate.

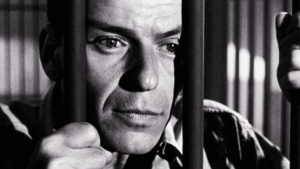

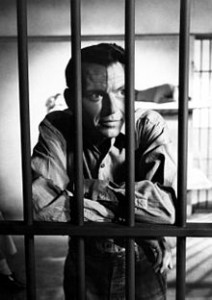

Based on the novel of the same title by Nelson Algren, this noir melodrama tells the story of a drug addict who gets clean while in prison, but struggles to stay sober in the outside world.

The specific addictive drug is not identified in the film–in the book it was morphine–adapted to the screen by Walter Newman, Lewis Meltzer, and Ben Hecht (uncredited).

Detailed Synopsis

In the first scene, Sinatra’s Frankie Machine, a drug addict, is released from prison ready to begin anew life with his only asset, a set of drums. He returns to his run-down neighborhood in Chicago’s North Side, having been cleaned up in prison. He befriends the good Sparrow (Arnold Stang), who sells homeless dogs and perceives him like a young brother. However, Schwiefka (Robert Strauss), former illegal card game partner, and Louie (Darren McGavin), former drug dealer, interact with Frankie in different ways, based on their shady motivations.

In the first scene, Sinatra’s Frankie Machine, a drug addict, is released from prison ready to begin anew life with his only asset, a set of drums. He returns to his run-down neighborhood in Chicago’s North Side, having been cleaned up in prison. He befriends the good Sparrow (Arnold Stang), who sells homeless dogs and perceives him like a young brother. However, Schwiefka (Robert Strauss), former illegal card game partner, and Louie (Darren McGavin), former drug dealer, interact with Frankie in different ways, based on their shady motivations.

Frankie’s wife, Zosh (Eleanor Parker), is immobile in a wheelchair, after a car crash caused by Frankie driving drunk. In a shocking scene, we realize she is fully recovered, but has pretended for years to be disable and dependent so that Frankie stay with her. She wears a whistle around her neck, which she uses to alert her neighbor Vi (Doro Merande), when needed. Zosh smothers her husband, hindering his attempt to make a better life for himself as a drummer in a big band.

Some relief from his domestic oppression and good time come via his old flame, Molly (Kim Novak), a hostess in a local strip joint, who lives in the apartment below Frankie’s. Unlike Zosh, Molly encourages his dream to become a drummer. For a tryout, Frankie asks Sparrow to get him a suit, but the suit is a stolen one and he is sent back to the Police. He reluctantly accepts Schwiefka’s offer to pay the bail, when he spots a drug addict out of control. With no job and mounting marital pressures, he succumbs and goes back to drugs and card games, which alienates Molly from him.

In one of the film’s most melodramatic sequences, Frankie attacks Louie and ransacks his house, but can’t find his drug stash. At the audition, subject to withdrawal symptoms, he ruins his chance of getting the job. Louie discovers that Zosh has been faking her paralysis, and the scared woman, pushes Louie over to his death, escalating but risks when Frankie is accused of Louie’s murder.

In one of the film’s most melodramatic sequences, Frankie attacks Louie and ransacks his house, but can’t find his drug stash. At the audition, subject to withdrawal symptoms, he ruins his chance of getting the job. Louie discovers that Zosh has been faking her paralysis, and the scared woman, pushes Louie over to his death, escalating but risks when Frankie is accused of Louie’s murder.

After learning that the police is looking for him, Frankie goes through a grueling withdrawal process. Summoning courage, he decides to leave Zosh and start anew. Desperate to keep Frankie, she gives herself away, and tries to runs, but, trapped, she throws herself off the balcony to her death. Frankie watches these events in dismay before walking away with Molly.

Scandals and Controversies

Nelson Algren’s “Man with Golden Arm” was a national best-seller before it became a controversial film. The story of one man’s fight against heroin addiction was thought to be impossible to bring to the screen because the Hays Office code outlawed even the mention of drugs in Hollywood films. The inflexible rule read: “The illegal drug traffic must not be portrayed in such a way as to stimulate controversy concerning the use of, or traffic in, such drugs; nor shall scenes be approved which show the use of illegal drugs, or their effects, in detail.” In retrospect, this rule is absurd.

The Hays Office made it clear from the start of Preminger’s version of the novel that the Seal of Approval would definitely be withheld from the film. Preminger, who had previously fought the Hays Office and the Legion of Decency on “The Moon is Blue,” was not perturbed. The plan, which turned out to be a successful one, was simply to release “Man with Golden Arm” without the Seal and to see what would happen.

The Hays Office made it clear from the start of Preminger’s version of the novel that the Seal of Approval would definitely be withheld from the film. Preminger, who had previously fought the Hays Office and the Legion of Decency on “The Moon is Blue,” was not perturbed. The plan, which turned out to be a successful one, was simply to release “Man with Golden Arm” without the Seal and to see what would happen.

How should the problem of drugs be treated in a mainstream picture Realistically or Hollywood-style This was one of the big questions the film raised. Of course, “Man with Golden Arm” was a 1950s Hollywood movie, and Frank Sinatra’s successful recovery in the film was necessarily guaranteed by Hollywood conventions of the time.

However, Harry J. Anslinger, commissioner of the United States Bureau of Narcotics, publicly condemned the film while it was still in production because of its planned happy ending. Anslinger claimed that this was a “100 percent Hollywood treatment.” Preminger promptly lashed back at Anslinger. This incident catapulted the inner-industry controversy over the film straight into the papers.

After Preminger’s attack on Anslinger, the commissioner counterattacked, accusing Preminger of talking back only to buoy the box office for the film. This became one of the main arguments against the film–that it unduly played on a serious social problem just to make money. By the time the movie was completed and released, the controversy was raging everywhere.

The only concession Preminger made to the censors was that a scene depicting the preparation of heroin for shooting up was cut by 37 seconds. This was due to the request of the New York Statute. The scene was at some later time restored to its original length.

The only concession Preminger made to the censors was that a scene depicting the preparation of heroin for shooting up was cut by 37 seconds. This was due to the request of the New York Statute. The scene was at some later time restored to its original length.

When the Hollywood Production Code officially banned the finished film, it was joined by the MPAA. However, for the first time in the film industry’s history, none of the theaters that had booked the film were afraid to go ahead and show it. This was a turning point. It showed that the breakdown of the authoritarian Code had begun.

The weakened Code soon had to face its adversaries in public debate. The Production Code’s disapproval was given pro and con consideration on “The American Forum” panel show on NBC. The broadcast featured Preminger, Jerry Wald, and William Mooring (film editor for the Catholic magazine Tidings) debating the Code’s decision, with Stephen McCormick as moderator.

The Legion of Decency, meanwhile, gave “Man with Golden Arm” a safe B rating, which was a plus for the film and Preminger, and a big negative for the Code. Preminger claims in his autobiography that, “the Legion most likely wanted to avoid losing another battle after The Moon is Blue.”

Along with the B rating, however, the Legion expressed its qualms about the film: “This film is of low moral tone throughout because it tends to minimize the moral obligations of all the principal characters. It treats in terms of morbid sensationalism with narcotic addiction and in so doing fails to avoid the harmful implications relative to this moral and sociological problem. It also contains suggestive costuming, dialogue and situations.” Many of the film’s detractors shared the League’s judgment.

One of the detractors was Variety’s Joe Schoenfeld, who also saw The Man with the Golden Arm” as an immoral film: It makes a hero out of a junky; it glamorizes his romantic life; it puts a gloss on skid row joints and strippers; it pictures police as bystanders to obvious law-breaking; and, finally, it has the junky walking off to further adventures with a doll of the type of beauty that some smoke opium to dream about.”

Many critics, like Schoenfeld, complained of the film’s romantic depiction of the addict’s life. Dick Williams wrote in the Mirror-News that “here is a world of floozies, but the central figure had two gorgeous dames crazy about him.” Williams also noted that, “When Sinatra gets hopped on H he does nothing bad.”

Three of Los Angeles radio stations, KBIG, KMPC and KLAC, apparently siding with the film’s opponents, refused to air advertisement spots for the film because the film would raise harmful curiosity about heroin. Actually, this ban was due to the behind-the-scenes work of narcotics officials, who persuaded the radio stations to refuse the commercials. By the way, the film was banned in Spain, also based on this “harmful curiosity” argument. Spain incredulously claimed to have no dope problem.

It’s noteworthy, to be fair, that “Man with the Golden Arm” also had its strong supporters. A Variety article entitled “Morals, Geography and Compromise” asked the question that was on many people’s minds: “Is a great national problem never to be examined on the screen There are a lot of reefer-happy kids. Narcotic pushers today make the Prohibition goons look like tomboys, if only on the angle that a slaphappy drunk is still many times a nicer victim than a junkie.”

Preminger himself was the film’s most vocal supporter. In a New York Times interview, he took a similar line of attack to the Variety article: “Why should movies be treated like a stepchild with no brains Television deals with it. I’ve seen two or three shows where narcotics were important.”

Preminger even went so far as to blame Hollywood for America’s drug problem. He argued that it was actually because the Motion Picture Association had banned narcotics from films around 1930 that dope addiction had become an enormous problem in the States. The Man with the Golden Arm truly raised the question of exactly how Hollywood influences the American public.

Of course, “Man with Golden Arm” seems tame today. It is mild compared to “Drugstore Cowboy,” “The Story of Christianne F.,” “Light Sleeper,” “Lenny, “Rush” or even the Cheech and Chong movies.

A court case, Maryland vs. “The Man with the Golden Arm” eventually went to the Supreme Court, establishing further freedoms for Hollywood films. Six years after the film was released, even the Code had to backtrack and approve the film. However, albeit tame this was Hollywood’s first attempt at a drug movie, and was certainly an eye-opener about dope addiction, and particularly withdrawals, to many Americans.

Oscar Nominations: 3

Best Actor: Frank Sinatra

Art Direction-Set Decoration (black/white): Joseph C. Wright and Darrell Silvera

Original Score: Elmer Bernstein

Oscar Context:

The winner of the Best Actor Oscar was Ernest Borgnine for “Marty.”