Like Vincente Minnelli’s 1952 Hollywood melodrama The Bad and the Beautiful, his 1955 film The Cobweb set out to reveal the inside workings of a sheltered, enclosed society.

My Biography of Minnelli

And like the former, it centers on people whose professional careers represent efforts to compensate for their emotional problems, specifically lonely, frustrated domestic lives.

Grade: B (***out of *****)

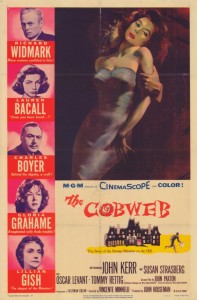

“The Cobweb” is yet another of producer John Houseman’s star-laden ensemble that aimed at classy entertainment, but one with broader mass appeal. To that effect, Minnelli’s film boasts a new generation of actors, including Susan Strasberg (Method guru Lee Strasberg’s daughter) and especially John Kerr, then touted as the next James Dean (who would die in a car accident just two months after the release of The Cobweb, on July 15, 1955)

The film is based on the novel by William Gibson (using pseudonym William Mass), who got first-hand knowledge of the private mental hospital during his wife’s work as staff member of the Menninger Clinic. The adaptation is by John Paxton, whose scripts for Crossfire and The Wild One showed sensitivity to explosive, socially relevant melodramas.

Author Gibson supported all the changes recommended by Minnelli and the screenwriters. All along Minnelli held that the film’s impact would depend on the intense directness with which the audience could identify with the characters. In the book, the doctor’s wife suffers from frigidity, aggravated by menopause. A decision was therefore made to subject the chief character of the doctor to the tensions of a more normal marriage.

The Cobweb became a personal film for Minnelli in more senses than one. The psychiatric setting held a perverse fascination for Minnelli, after years of nursing Judy through various institutions, including Menninger. Judy had also spent time at that clinic.

The bizarre plot, and some of the characters, touched a chord, playing to his idiosyncrasies. The films central conflict was close to Minnelli’s heart. The hostility between the clinic’s patients and the warring staff erupts over a seemingly trivial aesthetic matter, the choice of new drapes for the lounge. But for an aesthete like Minnelli, the issue was not trivial at all; it was essential. Decor reflected not only aesthetics but deeper values and moral issues, too.

To achieve greater accuracy, Minnelli brought Gibson out to rework the dialogue, and to supervise the construction of the sets. In the end, despite great many efforts, Minnelli was dissatisfied with the shooting script and the final cut.

Richard Widmark portrays a clinical psychiatrist, Stewart McIver, torn between his domestic family of his wife Karen and their two children, and the surrogate family that he cultivates in his clinic with attractive staff worker Meg (Lauren Bacall), and disturbed adolescent artist, Stevie (John Kerr). Meg and McIver ask Stevie to design new drapes for the clinics library as a therapeutic exercise, not realizing that Karen and a matronly bureaucrat at the clinic (Lilian Gish) already have assumed responsibility for doing it.

This plot device generates several intricate familial, social, and professional conflicts, none of which, Minnelli held, is resolved satisfactorily. Irony abounds, for at the end, the library still remains without drapes.

Overall, Minnelli’s most dynamic visual stroke was evident only in the climactic sequence of Stevie’s escape from the asylum. For this scene, Minnelli used an even more neurotic music than Miklos Rozsa provided in his Waltz for Madame Bovary. He therefore asked for more dissonant brasses from composer Leonard Rosenman, who had established a name for himself a year earlier with his wonderful score for the first James Dean film, Elia Kazans East of Eden.

Minnelli could not bring to The Cobweb the same vigor or pizzazz that had sparked The Bad and the Beautiful four years earlier. Even so, despite lack of forceful style, The Cobweb was a highly personal film. Minnelli interweaved all the themes of his previous works, specifically the artist as an outsider, careers as compensation for personal disappointment, the struggle between maintaining individualism (at the price of loneliness) and the need to conform and integrate into a larger community. The film’s underlining motif was social and emotional isolation, which marked each of the team’s members.

But The Cobweb is also marred by the lack of authenticity. The clinic on screen doesn’t resemble any particular or remotely realistic institution. The group scenes play out like Minnelli’s customary party scenes, a nervous mix of chatty cosmopolitans and flinching wallflowers.

Take the brief encounter between Karen McIver (Gloria Grahame) and her husband’s young charge, in which they discuss the symbolism of flowers and the tormented genius of Les Fauves. “Isn’t it enough that they have color and form Grahames Karen says. The gladioli flowers on the back seat of Karen’s station-wagon inspire Stevie to brood over Andre Derain’s deathbed cry, “some red, show me some red, and some green!”

Interestingly, the picture’s domestic scenes are more harrowing than the climax at the clinic. The Cobweb was the first Minnelli melodrama to reflect his ever-growing cynicism about family life in the affluent 1950s. All his future domestic melodramas, Tea and Sympathy, Some Came Running, and Home from the Hill, center on presumably respectable and happy couples who actually loathe each other and who are miserably unfulfilled.

Some film scholars, like Thomas Schatz, consider Minnellis 1950s melodramas, The Cobweb, Tea and Sympathy, Home from the Hills, and Two Weeks in Another Town, as a distinctive genre that could be named “the male weepie.” For them, it was a type of film that follows the narrative strategy of exploiting a superficial plot device, in order to camouflage some more serious or deeper social criticism related to the relationship between therapy and patients.

Whether Minnelli examines angst-ridden familial relationship in a mental hospital (The Cobweb), on a college campus (Tea and Sympathy), a small town (Some Came Running), or even within a foreign-based Hollywood production (Two Weeks in Another Town), most of his melodramas are engaged with the search for the ideal (or optimal) nuclear family. In most of these features, Minnelli contrasts the protagonists of natural or biological family with a professional group that’s equivalent of and functions as a surrogate family.

In The Cobweb, the emphasis on family interaction is highlighted by the fact that McIver is a Freudian psychoanalyst, who doesn’t get along with his wife or son. “Why don’t you analyze my Oedipus complex, or my lousy father?” Stevie asks McIver early on in the film. To which the psychiatrist responds, “I’m not your father, and I won’t run out on you like your father did.”

As good a surrogate father as McIver is on the job, though, his performance of domestic skills and his demonstrations of feelings on the home front are lacking, to say the least. He doesn’t communicate well with his wife, either verbally or sexually, and he is a complete stranger to his own children. When McIver’s daughter is asked at school what she wants to be, she replies, “One of Daddy’s patients.”

The McIver household in The Cobweb is the setting for a misbegotten marriage. By day, it has the look of a sterile upscale hominess of a W.J. Sloane’s window display. By night, it shifts to gothic atmosphere. Minnelli makes sure to place the doctor and wife in the shadows of respective bedrooms, while the children are in the background. The solemn little boy plays chess against himself, whereas the girl Rosie wants to be a mental patient when she grows up. Compared to this troubled family unit, the hospital represents unity and harmony.

Minnelli identified with the story’s young patient, Stevie, and his quip: “You can’t tell the patients from the doctors.”

A decade later, when Kirk Douglas told Minnellii about his plan to adapt One Flew Over the Cuckoos Nest to the screen and cast himself in the lead role (which was eventually played by Jack Nicholson in an Oscar-winning turn), Minnelli was quick to point out that The Cobweb was the first film to show the fine line between sanity and madness, and that at times there really are no differences between the inmates and their therapists, with both sets of characters being emotionally or mentally troubled.

Consider the following exchange between a patient and his psychiatrist: “Your’e supposed to be making me fit for a normal life. What’s normal? Yours? If it’s a question of values, your values stink. Lousy, middle-class, well-fed smug existence. All you care about is a paycheck you didn’t Earn, and a beautiful thing to go home to every night.”

Unlike other Minnelli’s melodramas, The Cobweb was not popular at the box-office. The director attributed the failure to the studio’s poor and “wrong” marketing of the kind of movie that it was.

Did the tale have too many figures (issues and problems) for its own good? Lack of genuinely sympathetic characters? Stiff and awkward acting from John Kerr? A miscast Richard Widmark, who lacked strong chemistry with both his wife (played by Gloria Grahame) and his love interest (Lauren Bacall)?

In hindsight, artistically speaking, The Cobweb was not as impressive with Minnelli’s melodrama that preceded it, The Bad and the Beautiful, or the one that followed it, Some Came Running, in 1958.

Credits

Produced by John Houseman

Associate producer: Jud Kinberg

Assistant Director: William Shanks

Screenplay: John Paxton; additional dialogue William Gibson, based on the novel by Gibson

Cinematography: George Folsey

Art Direction: Cedric Gibson, Preston Ames

Set Decoration: Edwin B. Willis; Keogh Gleason

Music: Leonard Rosenman

Editing: Harold F. Kress

Color consultant: Alvord Eiseman

Print process; Eastmancolor

Graphic design execution: David Stone Martin

Recording Direction: Dr. Wesley C. Miller

Hair Stylist: Sydney Guilaroff

Makeup: William Tuttle

Running Time: 124 Minutes

Budget $1,976,000

Box office $1,978,000

Cast:

Dr. Stewart McIver (Richard Widmark)

Meg Faversen Rinehart (Lauren Bacall)

Dr. Douglas N. Devanal (Charles Boyer)

Karen McIver (Gloria Grahame)

Victoria Inchy (Lillian Gish)

Steven W. Holte (John Kerr)

Sue Brett (Susan Strasberg)

Mr. Capp (Oscar Levant)

Mark (Tommy Rettig)

Dr. Otto Wolff (Paul Stewart)

Lois Y. Demuth (Jarma Lewis)

Miss Cobb (Adele Jergens)

Mr. Holcomb (Edgar Stehli)

Rosemary (Sandra Descher)