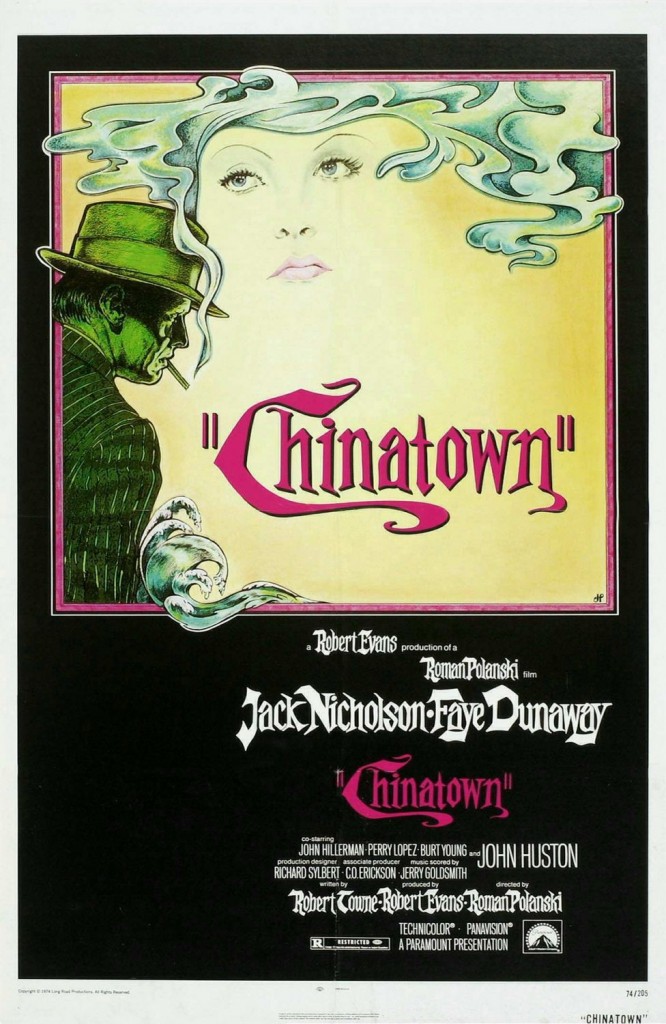

Starring Jack Nicholson and Faye Dunaway, Chinatown is one of the best film noirs ever made, a quintessentially zeitgeist movie of the 1970s, even though it is set in the 1930s.

Grade: A (***** out of *****)

Arguably, this bleak feature is one of Roman Polanski’s three or four masterpieces; the others being Knife in the Water, Repulsion, and Rosemary’s Baby.

Loosely based on an actual incident in Los Angeles’ history, Robert Towne’s screenplay clothes its political symbols within a hardboiled pulp detective yarn. At once a melancholy and savage film, “Chinatown” is ample proof that film noir is alive and well in American cinema.

Our Grade: A (***** out of *****)

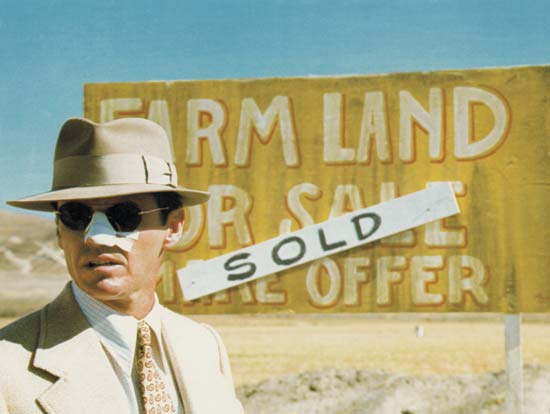

A bizarre, fascinating mystery in the Dashiell Hammett-Raymond Chandler tradition, the tale is set in L.A, in 1937, when the city is suffering through a major drought. J.J. Gittes (Nicholson), an ex-cop and private detective specializing in “matrimonial” work, is hired by a mysteriously attractive woman, Evelyn Mulwray (Dunaway) to find out whether her husband, L.A.’s Water Commissioner Hollis Mulwray, has been cheating on her.

The story makes front-page headlines and Gittes learns he has been duped in a plot to discredit the Commissioner, whose opposition to construct a water reservoir in the San Fernando Valley, costs him his life, when his body is found in the ocean, though it’s not clear who and where exactly he had been murdered.

Towne devises a metaphor in “Chinatown” that’s easily applicable to the noir genre. Many noir characters have shadowy pasts and are plagued by subconscious fears. In this film, Gittes’ fall guy worries stem from “Chinatown,” a place, a state of mind, and a spiritual landscape, where monstrously corrupt deeds are performed in the name of progress and modernization.

The mere mention of “Chinatown” causes people to respond in the manner that children react to the “Bogeyman.” At one point, Gittes himself refers to it obliquely: “You may think you know what you’re dealing with, but believe me, you don’t. Talking about the past bothers everyone who works in Chinatown, because you can’t always tell what’s going on…”

If “Chinatown” feels more authentic and precise than other Hollywood pictures about L.A. as a new emerging city, it’s largely due to first-hand familiarity of native son, writer Robert Towne, who deservedly won the 1974 Original Screenplay Oscar. His writing benefits from meticulous research and attention to the smallest detail in the text, subtext, context, and visuals.

The movie had been conceived for Nicholson as Jake Gittes, and for Robert Evans as producer, then head of Paramount. Director Polanski joined later on, and his squabbles on the set with femme fatale-diva Faye Dunaway and with Towne over what he perceived as a soft ending have received a lot of press over the years.

Ultimately, I think Polanski was right, for his conclusion is more coherent with the film’s overall cynical and downbeat tone. As is known, Polanksi insisted on reaffirming at the end Noah Cross (Evelyn Mulwray’s father and city boss) imperial power over the city and its authorities. He is also responsible for having Evelyn Mulwray killed in a brutal way; she’s shot in the eye in front of her Kathryn, daughter and sister. For the second time in Chinatown, Gittes is left powerless and helpless, before being dragged from the scene. The last image of Cross’ embracing his daughter-and-granddaughter, suggesting that they go “home,” is truly creepy and chilly since the whole notion of “home” is dubious in this incestuous yarn.

From first frame to last, “Chinatown” is great spectacle film, an extremely enjoyable experience that bears repeated viewing due to rich, multi-nuanced texture. As director, Polanski is in complete control of every aspect of the filmmaking. He also makes an unforgettable cameo as the midget honcho (billed as “The Man with Knife”), who cruelly jabs Nicholson’s nose, accounting for the actor having to wear a huge bandage for the rest of the picture.

As Noah Cross, John Huston gives an expansive, grandiose performance that utilizes his deep basso voice. Also well-cast is Dunaway as the beautiful and mysterious femme fatale, though it takes some times to get used to her mannerisms. Over the years, the scene in which Gittes demands to know the truth about Kathryn, smacking Evelyn across the face while she claims, “She is my sister. She is my daughter,” is the only excessively melodramatic and thus has become high-camp, subject to imitation.

Nonetheless, the film belongs to Nicholson, who guides the viewers throughout with a bravura performance as he digs deeper and deeper into the maze. Most of the events are shot from the POV of Gittens, who in the hands of Nicholson emerges as one of his most complex and touching characters. At the height of an already brilliant career, “Chinatown” followed Nicholsons work in “The Last Detail” in 1973 and preceded “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” (1975), for which he finally won the Best Actor Oscar.

In 1990, the eagerly-waited sequel, “The Two Jakes,” directed by Jack Nicholson, was such a disappointment that it highlighted Polanski’s contribution through absence; watching “Two Jakes” you kept thinking, “how would Polanski have handled this scene In “Chinatown,” each and every piece finally fits into intricately constructed general puzzle, and nothing is extraneous, unlike “Two Jakes,” which has too much of a (preposterous plot) and not enough characterization or mood.

While most critics are impressed with the film’s dual mood of cynicism and melancholy, for David Denby, the dominant tone is that of sunset oranges, as if the disappearing agricultural splendor of Los Angeles is giving off an afterglow.

Shrewdly, Towne posits the control over water supply as the City’s life source and key to its future, which also provides the structural and symbolic underpinnings of the picture as a whole. It’s noteworthy that in the sequel, the scarce resource is not water, but oil.

The picture’s central metaphor of picture is lack of knowledge: Nobody knows what’s going on and what the future holds, for the city and the country. In “Chinatown,” even the most seemingly innocuous of natural elements, water, become a political commodity, causing the most heinous and corruptive actions. The movie’s two central metaphors are water and glass (as in glass and as in eye glasses), which lap against one another with a deceptively smooth but scary ease. In one of the film’s climaxes, a pair of bi-focal glasses is found in Hollis’ pool.

Nicholson’s Gittes scratches the surface and finds greed, capitalists operating like criminals, controlling the fate of California at a crucial moment of its evolution. Reflecting the country’s national cynical mood in 1974, the movie emphasizes the futility of honest individuals fighting against evil corruption.

Nicholson’s Gittes scratches the surface and finds greed, capitalists operating like criminals, controlling the fate of California at a crucial moment of its evolution. Reflecting the country’s national cynical mood in 1974, the movie emphasizes the futility of honest individuals fighting against evil corruption.

As the critic Richard Combs noted, “Chinatown” is a zeitgeist movie that, though set in the late Depression era, in many way reflects the politics of the early 1970s, specifically the powerful force of Nixon’s imperial presidency, and American politics as a Byzantine maze of lies and secrets–behind closed doors–of the highest order.

In one of the film’s most powerful and emotionally troubling scenes, Gittes slaps Evelyn to make her confess he past. With each swift blow, the effect chages rapidly, from shock to repulsion to sorrow to utmost compassion.

Running time: 131 Minutes

A summer release–it opened on June 20, 1974–Chinatown was a commercial success (though not a huge hit), earning $29.2 million at the box-office, against a budget of $6 million.

Oscar Alert

Nominated for 11 Academy Awards, Chinatown won a much-deserved Oscar for Robert Towne’s Original Screenplay.

See Essay on Chinatown at the 1974 Oscar Race, and a list of the film’s complete credits elsewhere.

One of the best film noir ever made, “Chinatown” is a seminal movies of the 1970s and one of the two or three Roman Polanski’s masterieces. It’s also one of my all-time favorite films. Hence, here is a list of complete credits for those who care–and like the movie as much as I do.

Creative

Director: Roman Polanski

Poducer: Robert Evans

Associate Producer and Unit Production Manager C.O. Erickson

Screenplay: Robert Towne

Technical Crew

Director of Photography: John A. Alonzo [Technicolor Panavision] Camera Operator: Hugh Gagnier Special Effects: Logan Frazee Sound: Larry Jost, Bud Grenzbach Sound Editor: Robert Cornett Music: Jerry Goldsmith Production Designer: Richard Sylbert Art Director: W. Stewart Campbell Set Design: Gabe Resh, Robert Resh Set Decoration: Ruby Levitt Costumes: Anthea Sylbert Wardrobe: Richard Bruno, Jean Merrick Makeup: Hank Edds, Lee Harmon Hairstyles: Susan Germaine, Vivienne Walker Casting Mike Fenton, Jane Feinberg Production Assistant: Gary Chazan Script Supervisor: Mary Wale Brown Assistant Director: Howard W. Koch, Jr. Titles: Wayne Fitzgerald Film Editor: Sam O’Steen

Songs

“I Can’t Get Started” by Ira Gershwin and Vernon Duke; “Easy Living” by Leo Robin and Ralph Rainger; “The Way You Look Tonight” by Jerome Kern and Dorothy Fields; “Some Day” and “The Vagabond King Waltz” by Brian Hooker and Rudolf Frimi

Cast:

Jack Nicholson (J.J. Gittes)

Faye Dunaway (Evelyn Mulwray)

John Huston (Noah Cross)

Perry Lopez (Escobar)

John Hillerman (Yelburton)

Darrell Zwerlin (Hollis Mulwray)

Diane Ladd (Ida Sessions)

Roy Jen (Mulvihill)

Roman Polanski (Man with Knife)

Dick Bakalyan (Loach)

Joe Mantell (Walsh)

Bruce Glover (Duffy)

Nandu Hinds (Sophie)

James O’Reare (Lawyer)

James Hong (Evelyn’s Butler)

Beaulah Quo (Maid)

Jerry Fujikawa (Gardener)

Belinda Palmer (Katherine)

Roy Roberts (Mayor Bagby)

Burt Young (Curly)

Elizabeth Hard (Curly’s Wife)

John Rogers (Mr. Palmer)

Cecil Elljott (Emma Dill)

Paramount (Penthouse-The Long Road Productions)

Released: Paramount, June 21, 1974

Running Time: 131 minutes

MPAA Rating: R