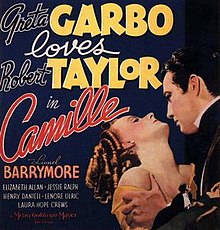

George Cukor’s Camille was the fourth–and the best–film version of the famous Alexander Dumas work, which had been done as a play and as an opera.

| Camille | |

|---|---|

Theatrical Poster

|

|

Director George Cukor said at the time: “Camille is a true and tried piece of work that can seem hackneyed unless the actress is really gifted and there’s happy meeting of actress and the part.”

Indeed, the film features the “divine” Garbo in one of her finest screen roles, as Marguerite Gautier, the tragic courtesan who must sacrifice her happiness in order to prove her love. Garbo’s performance received an Oscar nomination and was singled out by the New York Film Critics Circle.

If Cukor regretted being unable to shoot “Romeo and Juliet” in Italy, he felt the same way about being unable to shoot “Camille” in Paris., where the story takes place.

The PCA’s censors had many objections before they gave their approval. The following historical document provides a good indication of the cultural context in which the film was made. “The heroine is definitely an immoral woman,” the censors wrote, May 18, 1936. “There should be no ‘courtesans’ suggested in the film, other than Marguerite. Because of this, we recommend that Olympe be played as married to the old tottering Duke, and not as his mistress. We recommend that it be definitely indicated that Marguerite has no thought of resuming her old life of a courtesan after she breaks with Varville. It would be helpful if you could inject a note of repentance and regeneration. We believe it will be well to avoid any definite suggestion that Prudence is conducting a house of assignation, or engaged in the business of supplying women for immoral purposes.”

Camille also stars Robert Taylor as her lover, Armand Duval, and Lionel Barrymore as his aristocratic father.

Oscar Nominations: 1

Actress: Greta Garbo

Oscar Awards: None

Oscar Context

The winner of the Best Actress Oscar was Luise Rainer for “The Good Earth.”

Credits:

Directed by George Cukor

Produced by Irving Thalberg, Bernard H. Hyman

Written by James Hilton. Zoë Akins, Frances Marion

Based on La Dame aux Camélias by Alexandre Dumas, fils

Music by Herbert Stothart, Edward Ward

Cinematography William H. Daniels. Karl Freund

Edited by Margaret Booth

Distributed by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

Release date: December 12, 1936

Running time: 109 minutes

Budget $1,486,000

Box office $2,842,000

Cast

Greta Garbo as Marguerite Gautier

Robert Taylor as Armand Duval

Lionel Barrymore as Monsieur Duval

Elizabeth Allan as Nichette, the Bride

Jessie Ralph as Nanine, Marguerite’s Maid

Henry Daniell as Baron de Varville

Lenore Ulric as Olympe

Laura Hope Crews as Prudence Duvernoy

Rex O’Malley as Gaston

Mabel Colcord as Madame Barjon (uncredited)

Mariska Aldrich as Friend of Camille (uncredited)

Wilson Benge as Attendant (uncredited)