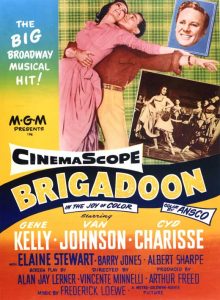

Revisiting Minnelli’s musical starring Gene Kelly and Cyd Charisse.

After the success of An American in Paris, which swept the 1951 Oscars, Freed signed Alan J. Lerner to a three-picture writing contract. The first one of these was the 1954 film version of Brigadoon, with Gene Kelly and Van Johnson, to be directed by Vincente Minnelli.

In the end, despite high expectations, Lerner was vastly disappointed with the end result. He described the picture as “quite wooden,” and informally criticized the acting of both Van Johnson and Cyd Charisse.

Our grade: C+

In 1953, The Band Wagon marked Minnelli’s tenth anniversary as Freed’s most valued director and a highlight for the Freed Unit, as one of the most celebrated production entities.

In contrast, a year later, Brigadoon signaled the end of sustained creativity for Freed. Up until now, the consistent success of Freeds musicals had withstood the changes that shook Hollywood during the post-War years. However, due to TVs increasing prominence, movie audiences declined rapidly, and many theaters were converted into supermarkets. Clearly, by 1954-5, the old studio system began to fade. Freed could no longer sign freely fresh talent from New York to long-term contracts.

Vulgar as it was, Minnelli’s Long, Long Trailer made money, what cannot be said about Minnellis Brigadoon, which turned out to be one of weakest film both artistically and commercially.

Brigadoon, the third collaboration between Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe, showed the first evidence of an onset creative inertia . This operetta in kilts was a surprise hit of the 1946-1947 Broadway season, when Celtic whimsy seemed to be in, as a smiliar musical, Finian’s Rainbow, was also on the boards.

In March 1951, MGM announced that Gene Kelley and Kathryn Grayson would head the cast of the new musical. But Kelly’s European plans stalled Brigadoon for two years, by which point MGM’s contract with Grayson had lapsed. The studio then decided to cast Moira Shearer, the dancer-actress of ballet melodrama, The Red Shoes, a magnificent picture that broke box-office records, which Minnelli admired. However, Brigadoon’s uncertain schedule made the Sadlers Wells Ballet nervous and unwilling to commit. Having lost Shearer as his ideal Fiona, Minnelli settled for Cyd Charisse, a good dancer but mediocre actress.

Although Kelly and Minnelli may not have been entirely in synch in terms of their musical conception of how to open up the play, they nonetheless enter into a peculiar working relationship, when the shoot finally began in December of 1953.

They improvised around the Lerner script as they went along, changing lines of the dialogue, touching and punching it up.

When Lerner heard about this via the studio grapevine, he stormed into Freed’s office, and then fuming, he stalked onto Stage 15. Confronting the offenders, Lerner firmly said, “I know I can write better than anybody on this set. So, if you want anything changed, ask me. After that change, there were no further changes.”

Lerner held that Brigadoon was one of Minnellis least vivacious efforts, despite its CinemaScope possibilities. Only the wedding scene and the chase that follows reveal Minnellis unique touch.

Before shooting began, Freed rushed to inform Lerner that Vincente is bubbling over with enthusiasm about Brigadoon. But, evidently, his heart was not in this film. Part of the problem was that Minnelli and Kelly, as Kelly later said, were not in synch. Early on, Minnelli made a mistake and confessed to Kelly that he really hadn’t liked the Broadway show and that it lacked cinematic possibilities.

Minnellis film was curiously flat and rambling, lacking in human warmth as far as the characters are concerned or easy charm that his other films with Kelly displayed. His direction lacks the usual vitality and smooth rhythmic flow. Admittedly, Lerners fairytale story was too much of a wistful fancy, with a minor tale at its center. Two American hunters go astray in the Scottish hills, landing in a remote village that seemed to be lost in time. One of the fellows falls in love with a bonnie ghost, which naturally leads to some complications.

Minnelli thought that it would be better to set the light story in 1774, before the bloody wars against England began. For research about the look of the cottages, he consulted with the Scottish Tourist Board in Edinburgh. But the resulting set of the old highland village looks artificial, despite the decor, the Scottish costumes, the heather blossoms and the scenic backdrops.

Inexplicably, some of the good songs that made the stage show stand out, such as Come to Me, Bend to Me; My Mothers Wedding Day, and There But For You Go I, were omitted from the final film, when its running time proved to be too long. Waitin for My Dearie and Ill Go Home With Bonnie Jean were given choral circulation and benefited from the stereophonic sound. Other songs, like The Heather on the Hill and Almost Like Being in Love, had some charm, though not enough to sustain the musical.

Moreover, the energy of the stage dances was lost in the transfer from play to screen. This was odd, considering that Kelly and Charisse were the dancers, and had done great work separately and together before. For some reason, their individual numbers were too mechanical and lacking invention. What should have been wistful and lyrical became an exercise in trickery and style.

With the exception of The Chase, wherein the wild Scots pursue a fugitive from their village, the other ensemble dances were dull. On stage, Agnes De Milles choreography gave the dance a special, energetic touch, whereas Kelly’s choreography in the film was mediocre at best and uninspired at worst.

It didn’t help that Kelly and Charisse made an odd, unappealing couple, lacking on screen chemistry. While Kelly looks thin and metallic, Charisse seem too solemn and earnest, practically frozen, especially when she needed to act. Charisse never had an interesting vocal range, even when she sang.

The rest of the cast was not much better. Van Johnson, as Kelly’s friend pouts too much. Barry Jones, Hugh Laing, and Jimmy Thompson act peculiarly as Scottish ghosts, to say the least.

Most theater reviewers could not understand the secret charm of Brigadoon when that whimsical musical had played on Broadway. Was it the dancing, the music, the decor, or the blend of all these elements that made it enjoyable?

As for the movie version, the N.Y. Times Bosley Crowther might have summed up the other critics’ opinion, when he described the screen version as pretty weak and synthetic Scotch.

One minor reward for the film’s otherwise lukewarm reception was the Box-office Blue Ribbon Awards, conferred upon Minnelli when the National Screen Council voted Brigadoon the “best picture for the whole family.” Unfortunately, that whole family audience decided to stay at home, and MGM declared a loss by year’s end.